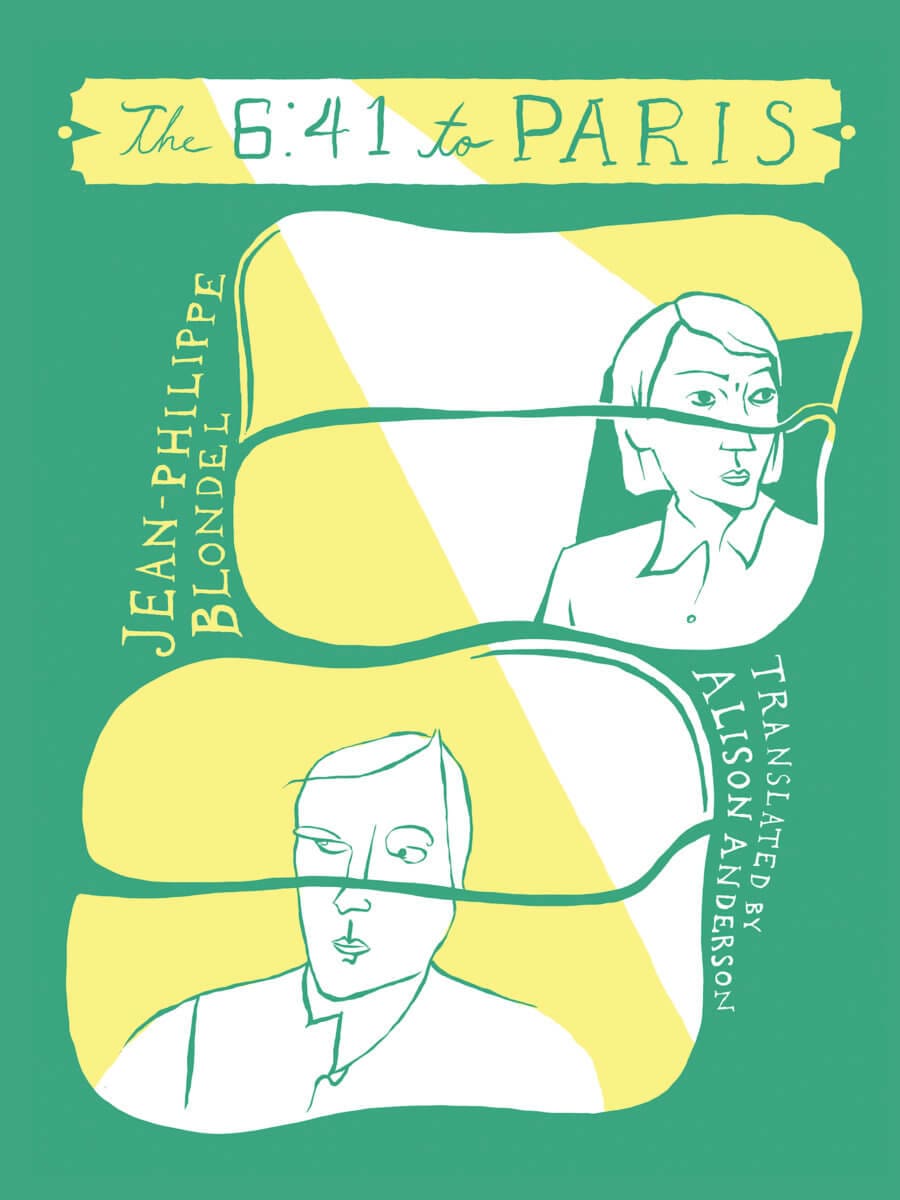

Cécile, a stylish 47-year-old, has spent the weekend visiting her parents in a provincial town southeast of Paris. By early Monday morning, she’s exhausted. These trips back home are always stressful, and she settles into a train compartment with an empty seat beside her. But it’s soon occupied by a man she instantly recognizes: Philippe Leduc, with whom she had a passionate affair that ended in her brutal humiliation 30 years ago. In the fraught hour and a half that ensues, their express train hurtles towards the French capital. Cécile and Philippe undertake their own face to face journey—In silence? What could they possibly say to one another?—with the reader gaining entrée to the most private of thoughts. This is a psychological thriller about past romance, with all its pain and promise.

Click Here to Download The 6:41 to Paris Reading Group Guide

Excerpt from The 6:41 to Paris

I love to hear the sound of the doors closing. It signals the beginning of an egocentric and self-indulgent interlude. For the next two hours, nothing can really happen to you. Everything is taken care of. You can decide to immerse yourself in a novel, or succumb to the trance of the music coming from your headphones. You can also vanish into the screen of your laptop, into e-mails, spreadsheets, numbers, reports, and establish a direct yet disembodied connection with the outside world.

I don’t do any of that. I daydream. Train journeys are rare opportunities to let go and lower my guard. Whereas in the Métro or the RER I can’t do that. I’m always on the alert.

The seat next to me has not been taken.

It stays empty.

The train starts to move.

I’m of two minds.

On the one hand, I’m relieved. It’s true that it’s a bit weird, the closeness you get in a railroad car. You’re only a few inches away from another person, another story, and you know that in the event of a crash, your skin will mingle with theirs. And then, these SNCF seats aren’t comfortable. A little more room would be great. Room enough to stretch out and fall asleep, if you feel like it, all the way to the Gare de l’Est—and catch up on lost sleep. We’re all trying to catch up on lost sleep. When you’ve got a neighbor, you have to sit up straight, almost like at school, and when the conductor goes by, you almost feel like raising a finger and saying, “Present.”

But another side of me wants to protest. Why am I the only one without a temporary partner? Am I giving off the sort of body odor that immediately deters any hypothetical candidates? Am I that ugly? Do I frighten them? Intimidate? So here I sit, the only singleton in the car—isn’t there even some old biddy who could come and keep my thoughts from going round in circles? Or some vague acquaintance I could chat with about the weather or the passage of time?

I wonder what the other passengers think when they look at me. They see a woman who is neither young nor old, fairly well preserved. A somewhat inscrutable expression, lips that could stand to be a little fuller, a deep line across her forehead, two others on either side of her mouth. Light makeup. Nicely tailored clothes. Discreet elegance. Relatively slim figure. Why isn’t she traveling first class?

For the simple reason that the 6:41 is a regional train, where the differences in comfort between first and second class are minimal. And besides, the number of first-class seats has been so drastically reduced that the half-car devoted to first is often jam-packed, while there are still empty seats in second class. Well, as a rule. Today the entire train has been swamped. All that’s left is the orphaned seat next to me. A privilege I would not have enjoyed in first class, where I would probably be stuck next to some corpulent senior executive reeking of aftershave, who would spend the entire time calling his superiors or his underlings, in spite of the notice asking for “cell phones in sleep mode.”

And besides, I like to travel second class. I feel like this is where I belong. My accountant laughs at me. He reminds me that Pourpre et Lys is one the trendiest shops around. That with two stores in Paris, one in Bordeaux, one in Lyon, and projects to expand all over France, I should start getting used to the idea that I have become an entrepreneur. Someone who in the decade ahead will count for something in the business world. In spite of the crisis, or because of it, organic beauty products have a bright future—particularly when the prices are still reasonable and the emphasis is placed on respect for regional traditions and on protecting the environment. Soaps that you cut yourself. Shampoo sold in reusable bottles. Recycled paper for advertising. Clear, concise labels made of plain brown paper, with the name of the product in black, and the ingredients below. Chic and sober. My brand name.

Valentine and Luc have begun to realize. Luc increasingly shuts himself away in his study. A sort of rivalry has arisen between us and he’s struggling, even though he’s known from the start that he’ll lose. Soon I’ll be earning much more money than him.

He’s been saying we have to move, we have to go back to Paris proper and leave our big house in the suburbs behind, the house with the garden where Valentine grew up. She couldn’t care less either way. She’s finishing her lycée and would rather stay with her friends for another year, but she’s already informed me that she intends to have her own studio in a lively quartier right in Paris next year. The forty-five minute commute to Sucy, no thanks. Luc also thinks I should stop taking the RER now, but it’s out of the question. My brand name is also about reducing the executive personnel’s expenditure. Even if I know that sooner or later we’ll move back to the city; for the time being, the business is too precarious, and it could vanish in a puff of wind—poor management, competition, unrealistic ambitions. I don’t want to add private loans to professional ones. At heart I’m still a provincial banker. After all, that’s what I was trained to do. After two years of training in marketing techniques I found myself unemployed. So I got a vocational training certificate in banking. I pictured myself behind the counter in a branch in the town where I grew up. Sometimes life takes us a long way from the place we thought we were headed. Sometimes that’s a good thing.

It has taken me quite a while.

That’s another trait of my character: I’m slow. But persevering. I thought about my project for years, when I was barely making ends meet as an admin in a financial analyst’s office, then in one of those multinationals that are all about new technologies, cell phones, computers, and consoles. I sat there watching while those gung-ho reps crushed their competitors. Then witnessed their fall a few years later. I learned how to be discreet and impeccable, without a fault. To be the model employee. To serve whoever was boss: old ones who couldn’t keep up to speed and sat around dreaming of their retirement in Sologne; young ones who were working up to their first heart attack; they could be warm, icy, scathing, offhand. And I figured out how it all worked. I spent a lot of time reading, too. Books about business, accounting, marketing. Luc just laughed at me. He thought I was immersing myself in all that in order to get closer to him, to what he did every day. Because Luc is one of those aging, interchangeable, middle management execs—for a stationery company that is relocating by the hour. They don’t even have a production site in France anymore. Hungary, Bulgaria, Poland: it’s all concentrated in Eastern Europe.

Luc had his hour of glory when he was able to negotiate a schedule that would allow him to take Valentine to school every morning and pick her up in the evening, when she was small. He would chat with the other moms and with the primary school teachers. He was their blue-eyed boy, they were ecstatic to see a man looking after his kids. Those very same women who think it’s only natural for the mother to do it—that’s their role, after all, it’s only fair. I hate women like them—because they are mainly women; they’re the very reason clichés have such a long life.

And then, eight years ago now, everything changed. I came out with my plan. And I embellished it with an ultimatum to my husband: either you go along with it, or we split up. I let him call me every name in the book, but I knew he’d be there for me. Because he still loves me. Because he admires my combativeness. And because the project was unbeatable. The banks had already given their consent. The 2001 crisis was behind us, the 2008 crisis was still to come. And the banks felt like investing.

I have a good relationship with my husband.

Often difficult, but solid.

We’re a team.

We know each other inside out; we are perfectly acquainted with each other’s weaknesses and strengths. But we can still surprise one another. Last month, he suggested dropping everything in order to assist me if Pourpre et Lys really took off. That’s the verb he used, “assist.” With a smile, he pledged to be my vassal. I don’t know many men who are capable of doing that.

Well, by the looks of it I’m going to sit here by myself. I really don’t feel like consulting the latest figures or reading outstanding correspondence. I’ll go back to the book I bought at the station on Friday on the way down. Some sort of family saga set in northern Germany. Nothing great, but it’s restful. And that’s what I need this morning, rest. I’m on my way home from the weekend and I’m exhausted. It’s not a paradox. It’s my life.

Ah-hah, there’s a guy looking for somewhere to sit. He comes a bit closer. He stops. He glances at the seat. Hesitates. Keeps walking. Turns around again. I don’t look at him. I can just detect his movement at the edge of my vision. For a moment I think I’ve won, that his desire for comfort is about to collide with the invisible wall of my indifference. No such luck. He clears his throat quietly, his voice is somewhat hoarse. “Excuse me, is this seat taken?” God the idiotic phrases we say every day. I shake my head and sigh, just to let him know it really is a bother. I pull my bag out of the way and this time I decide to look him in the face.

Oh. My. God.