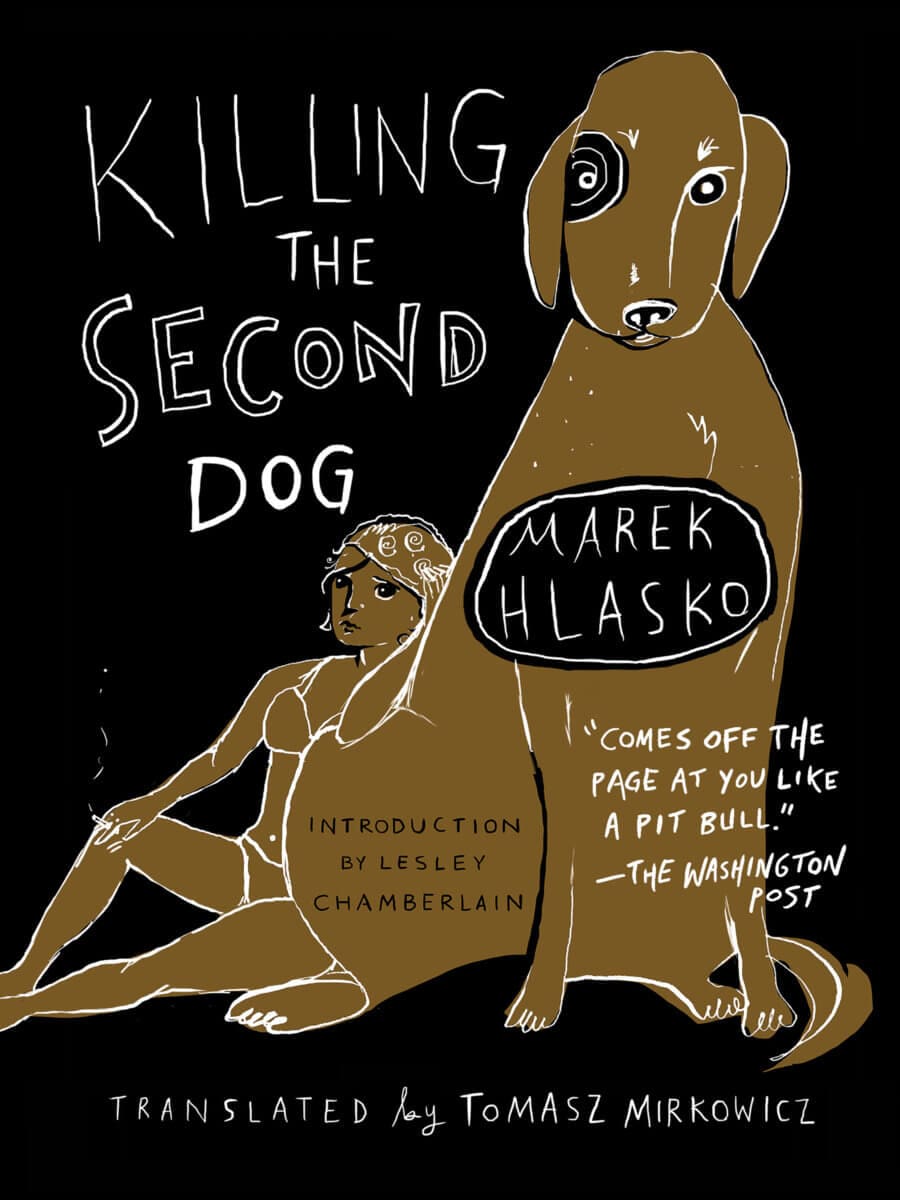

Robert and Jacob are two down-and-out Polish con men living in Israel in the early 1960s. They’re planning to run a scam on an American widow visiting the country. Robert, who masterminds the scheme, and Jacob who acts it out, are tough, desperate men, exiled from their native land and adrift in the hot, nasty underworld of Tel Aviv. Robert arranges for Jacob to run into the woman, who has enough trouble with her young son to keep her occupied all day. Her heart is open though, and the men are hoping her wallet is too. What follows is a story of love, deception, cruelty and shame, as Jacob pretends to fall in love with the American. But it’s not just Jacob who seems to be performing a role; nearly all the characters are actors in an ugly story, complete with parts for murder and suicide. Hlasko’s writing combines brutal realism with smoky, hardboiled dialogue, in a bleak world where violence is the norm and love is often only an act.

Excerpt from Killing the Second Dog

Our host was sitting on the terrace, reading a newspaper. His girlfriend was sitting next to him. When she saw us, she adjusted herself in her deck chair and lowered her gaze to the floor. It was meant to show her contempt. She was putting on an act. Men look only for peace and deliverance; women have to have something churning and shifting in their lives. They’re always very serious about how they feel and genuinely convinced that all those fleeting emotions they take for anger, love, or contempt are going to last forever.

“It’s us, Mr. Azderbal,” Robert said.

“Again?” Azderbal said.

“Didn’t it work out very well last time?”

“Sure. All it took to save my neck was two top lawyers and a doctor who testified that I happen to be partially insane. I don’t suppose you’ve come here to tell me of some new deal we could make together, huh?”

“That was an accident,” Robert said. “Somebody squealed on us.”

“Bullshit,” Azderbal said. “I’m not interested in any more shaky deals.”

I moved away and sat down on a deck chair next to the girl. She glanced at me in a brief, detached way. I could swear she’d been practicing that look in front of a mirror for the past three months, certain I was going to show up at any moment. But I hadn’t shown up; I had only come now with Robert because we were short of cash. I sat next to her, staring out at the dark garden, while behind our backs the two men continued their loud conversation.

“I need money,” Robert was saying. “I have to pay for his hotel, food, and all the rest.”

“And for the doctor,” the other added.

“Yeah, for the doctor, too. We need money for at least two, three weeks. He’s got to have a room and three meals a day; breakfast, lunch, and dinner. He’s got to be able to afford cigarettes, coffee, a deck chair at the beach, and a haircut and shave once in a while for him to look all right. And our dog, too. Our dog costs a pretty penny.”

“What does it eat?”

“Two pounds of pork a day,” Robert said. “Or do you expect me to cook it grits in my hotel room and mix that with canned kosher meat? Do you really? Well, maybe you’d eat that mush, but not this dog.”

“It’s too big. You should have bought a smaller dog, a poodle or a Pekingese; this one’s not a dog, it’s a monster, a fiend. No wonder it’s so expensive to feed.”

“Why don’t you just say outright that we should use a dead dog? That would come out cheapest. You don’t know how to make money because you don’t know what investing is all about. You want a hundred percent profit on every lousy deal you make; you haven’t learned that some of the best deals ever made often involve just fractions of one percent. You think like a small-scale herring merchant who has to make a hundred percent profit on every sale or else he’ll die of hunger.”

“You should have bought a smaller dog,” Azderbal insisted.

“Don’t teach me, Mister. The dog has to be big, happy, and full of life. It’s got to be loved and pampered by everybody. People have got to want to feed it chocolates, while it knows it can’t accept even one piece. Not even sniff it! That’s what I call a real dog. A dog like that becomes an issue. And then we have the makings of a tragedy. Don’t you see that? The dog has to have honey-colored stars in its eyes.” Robert came up to me and paused behind my chair; he was furious and awe-inspiring. “I have to tie the wings of my soul while he begrudges me a bit of meat for the dog.”

“He’s a jerk,” I said quietly, without turning my head. This was how we had planned it; I was to show the backer we despised him and his money, so he would think we had other options and that we came to him only because he lived so close. Azderbal and the girl twitched nervously. I continued to stare into the darkness.

“Why don’t you try it yourself?” Robert asked him. “Then you’ll see how difficult it is. You’ll see what these women are really like. All those old bitches out to save their lives. He suffers with them and pretends to be their savior. Two lonely hearts scarred by life and all that stuff. Try doing that yourself! You don’t want to? I’d like to see a woman give you forty piasters for a bus ride. Once I’ve seen that, I can lie down in my grave and die in peace. I’d know I hadn’t wasted my life.”

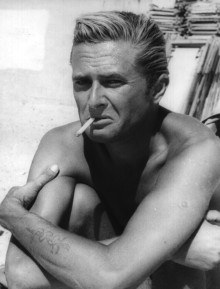

Azderbal looked at me. “He’s too old. He’s got the saddest kisser the world has seen since the death of that saint who used to sit on a pillar. What was his name?”

“St. Simeon the Stylite,” I said, which was a mistake on my part; I was supposed to remain silent throughout.

“Yeah, that’s the one,” Azderbal said. “What does he do with them in bed? They just cry together, or what?”

“We’ll divide the money three ways,” Robert said. “Like we did last time.”

“How much do you think it’ll be?”

“I don’t know. Maybe six hundred, maybe eight.”

“He’ll never score that much,” Azderbal said, looking at me. “His face is perfect for playing poker, but not for this kind of game. Either you’re blind, Robert, or else you don’t want to see it. Maybe you feel pity for him and don’t even know it. I can’t help you.”

“But he’s already made a pretty bundle this way,” Robert said.

“He’s finished, and you simply can’t see it. He’s done this trick a few times too many and everybody knows about it. Why don’t you find some handsome young fellow and bring him here? Then we might work something out. But don’t expect me to stake my money on this one.” He turned to the girl. “What do you think?”

“He’s too old,” she said. “He’s finished. What woman wants a guy who’s over thirty and looks ten years older? Women know a man like that’s never going to let them change him. And that’s all they ever really want.”

This was her way of getting even with me for having walked out on her two years earlier. She’d been waiting ever since for a chance to take her revenge and was probably disappointed she couldn’t do anything more to hurt me.

“Okay,” I said. “Let’s go.” I got up from the chair and shook hands with Azderbal and then with her. I added in a friendly voice, “Maybe we’ll make some other deal together, Azderbal.”

“If it’s worth my time, you can always count on me,” he said.

“And how do you find her?” I asked, stroking the girl’s face. “Has she learned to fake her orgasms yet? She used to be rotten at that. Probably because she’s got no sense of rhythm. Most women are deficient in that respect. Good night.”

We left.

“Azderbal is a thief,” Robert said.

“All Azderbals are thieves,” I replied.

“The worst Azderbal thieves used to live in Wroclaw,” Robert said. “If they didn’t swindle someone at least once a month, they’d be so depressed they’d need a shrink. Some of them even got suicidal.”

I didn’t answer. We walked back along the same street in silence. It was only when we were back in our hotel room that Robert finally spoke: “Don’t worry, tomorrow I’ll find us another backer. We don’t need a lot of money. Just enough for a few days.” He looked at the dog, which was lying stretched out on the floor, its red tongue hanging out. “But we do need it. There’s no way we can cut our expenses any further. No one mourns a Pekingese. Or a pug. Your dog has to capture the minds of all who see it. Otherwise there’ll be no tragedy.”

“Have you seen her yet?” I asked.

“I don’t need to. They don’t differ much from each other.” He moved to the window and stood there, gazing out; I looked at his white body gleaming with sweat, and the sight made me feel queasy. I wished there were a painting or a photograph hanging in the room. Anything you could fix your eyes on. But there was nothing. Only the bare walls, Robert, and the dog. I couldn’t look at the dog. “Yes,” Robert said, “they really don’t differ. All those lonely women getting on in years who want to get married one more time. With their money, which they’ve been saving all their lives.”

“A man wouldn’t do it,” I said. “You’d never find a guy who’d scrimp and save for fifteen years so he could marry some broad he’s never seen, has no idea even what she looks like. Robert, would you put your shirt on?”

“Why?”

“Your body’s disgusting. God only knows why I should have to look at it.”

He turned around. “That’s a very good line. An excellent line. You can say it to her at some point. I’ll walk off and you say, ‘I’ve spent the best years of my life with this guy. At night I’d look at his disgusting body and think to myself that I’d never be with a woman again.’ And then you take her hand and look into her eyes. Yes, that’s a beautiful line. You won’t forget it, will you?”

“No.”

“You can even stroke her body when you say it. Though maybe not. Better not overdo things. The dialogue’ll be enough.”

The desk clerk came into the room. “I knew it. …”

“Anything wrong with knocking?” Robert said, interrupting him.

“The cops are here!” the desk clerk shouted. “Go down and talk to them. I knew something like this would happen.”

I had to put my pants on again; they felt rough and hot, covered with dust. I went downstairs, but I didn’t feel like walking into the street. I stood in the doorway while the policemen sat in their car and stared at me.

“You again?”

“Good evening, sergeant,” I said. “Did I do anything to deserve such an unpleasant welcome?”

“Not yet. But you’re going to, aren’t you?”

“Gimme a break, sergeant. I’m just a sentimental guy.”

“You do it again, we lock you up.”

“There’s no law against falling in love.”

“Who’s the woman?”

“I don’t know. I love her is all I know. I love ’em all, sergeant. My father used to tell me when he was young he fell in love with every woman he met. I’m his spitting image. Is that so unusual?”

“You get a dog yet?”

“Would you like to see it?”

“Yeah, bring it here.”

I whistled and the dog bounded down the stairs. It settled at my feet. We looked like master and best friend posing for a picture. A perfect pair.

“My god! That’s not a dog, that’s a horse. Where did you get it?”

“We bought it.”

The sergeant turned to the other policeman. “Has anyone reported a dog missing? Check it over the radio.”

While the other cop switched on his radio, I said to the sergeant, “Come on, we paid a hundred pounds for this dog.”

“Does it eat a lot?”

“Sure. We feed it tripe… and other stuff.”

“You should try canned dog food,” the sergeant said. “Have you?”

“Yes, but the dog won’t eat any. He’s as spoiled as a movie star. We’ve had to cut down on our food to feed it properly. Robert’s lost two pounds.”

“The dog’s okay,” the second cop said, signing off.

“Let’s go then,” the sergeant said. But he kept staring at me. “I don’t want any problems with you two. So be careful. Believe me, one day you and your friend’ll go on a long prison diet.”

“You’re wrong,” I said. “And besides, Robert isn’t my friend. He’s my manager. That’s a big difference.”

“Who are you then?”

“His client,” I answered. “Good night.”

“Good night.”

They left. I turned around and went back to our room. Robert was already asleep. Lying in bed I looked again at his white body. It wasn’t a pleasant sight. In a few days I’ll be lying in a hospital bed, I thought, and the doctors will be fighting for my life, like the newspapers say. Will my body be as white and sweaty as his? For some reason, it didn’t matter to me. I threw the sheet off. It made me feel a bit cooler, but not much. I leaned over, touched the stone floor with my hand, and put the sheet on it. Then I lay motionless, beginning to smell the stink of my own sweat. Finally, I dropped off to sleep.