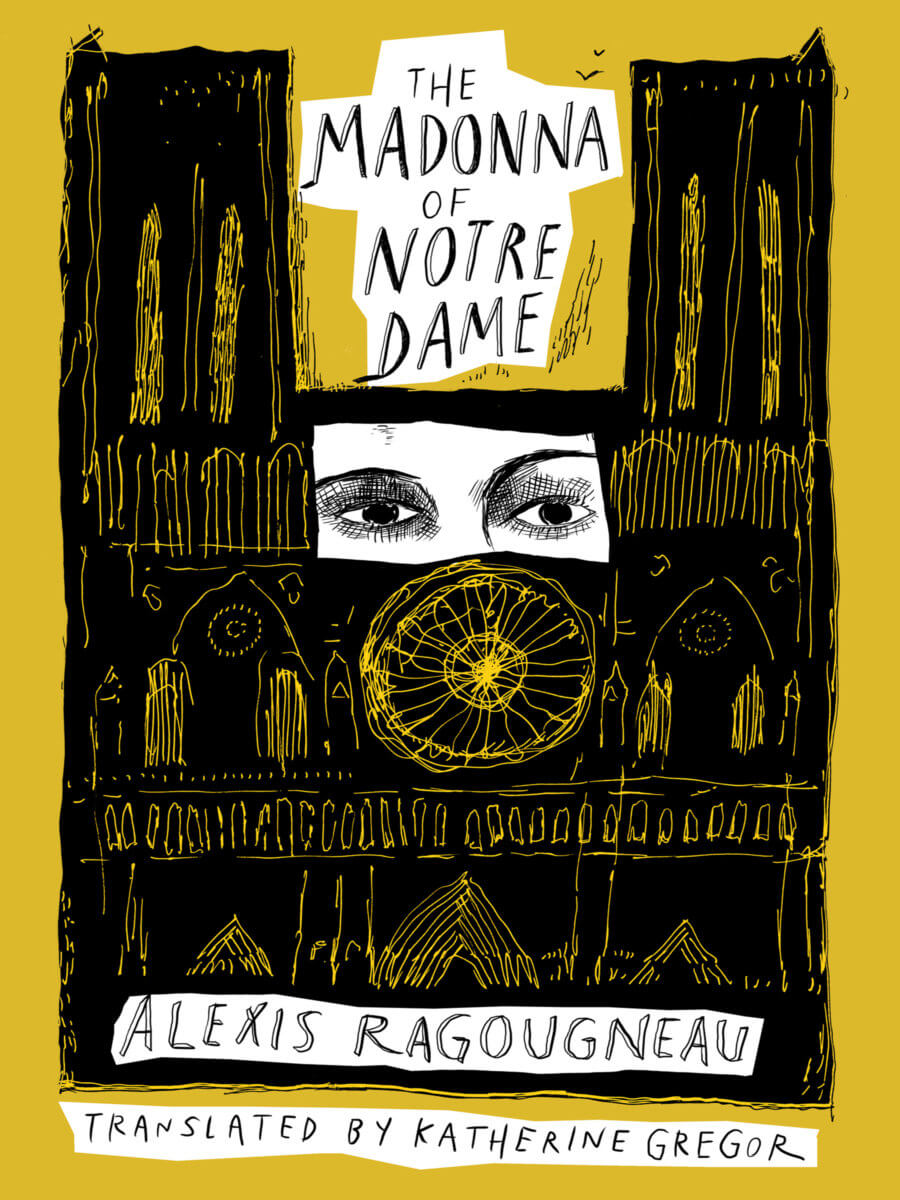

Fifty thousand believers and photo-hungry tourists jam into Notre Dame Cathedral on August 15 to celebrate the Feast of the Assumption. The next morning, a stunningly beautiful young woman clothed all in white kneels at prayer in a cathedral side chapel. But when an American tourist accidentally bumps against her, her body collapses. She has been murdered: the autopsy reveals disturbing details. Police investigators and priests search for the killer as they discover other truths about guilt and redemption in this soaring Paris refuge for the lost, the damned, and the saved. The suspect is a disturbed young man obsessed with the Virgin Mary who spends his days hallucinating in front of a Madonna. But someone else knows the true killer of the white-clad daughter of Algerian immigrants. This thrilling novel illuminates shadowy corners of the world’s most famous cathedral, shedding light on good and evil with suspense, compassion, and wry humor.

Excerpt from The Madonna of Notre Dame

“Gérard, there’s a bomb alert. In the ambulatory. Serious stuff this time. Big.”

His shoulder wedged in the doorway, a huge bunch of keys hanging at the end of his arm, the guard watched the sacristan fuss around, open all the sacristy cupboards, and pull out rags, sponges, silverware polish, while muttering expletives of his own composition at regular intervals.

“Gérard, are you listening? You should take a look, really. Fifteen years on the job, I’ve never seen anything like it. It’s enough to blow up the whole cathedral.”

Gérard interrupted his search and finally appeared to take an interest in the guard. The latter had just hung the keys on a single nail stuck in the sacristy paneling.

“Later on, if you like, I’ll go and see. Is that all right? Are you happy?”

“What’s going on today, Gérard? Haven’t you got time for important things anymore?”

“Look, you’re really pissing me off now. Thirty years I’ve been working here and it’s the same thing every year: every August 15th they have to make a total mess in the sacristy. And I can never find anything the next day. I have to spend two hours cleaning up. I don’t understand why it has to be so difficult. They arrive, they put on their vestments, they do their procession and their mass next door, they come back, they take off their vestments, and see you next year… Why do they have to go rummaging in the cupboards?”

“Tell me, Gérard, what have you lost?”

“My gloves. My glove box for the silverware. If I don’t have them I wreck my hands with their shitty products.”

“Do you want me to help you look? I’ve got time, I’ve just finished opening up.”

“Don’t worry, here, found them. I don’t know why it’s so hard to put things back where they belong, I mean, Jesus H. Christ …”

The guard fumbled in his pocket, inserted coins into the slit of the coffee machine, and pushed a button. He signaled goodbye to the sacristan and then, a steaming cup in his hand, started to walk back to the interior of the cathedral. Gérard caught up with him in the corridor.

“So tell me about your bomb … Worth seeing?”

“The works, I promise: the tick-tock, the time switch, and the sticks of dynamite.”

“OK, I’ll go see later, before the nine o’clock mass. Might still be there. Where’s your explosive device again?”

“In the ambulatory, outside the Notre-Dame-des-Sept-Douleurs chapel. You’ll see—impossible to miss.”

The nave was slowly beginning to fill with its daily stream of tourists. Between eight and nine in the morning, they were mostly from the Far East: Notre-Dame was the opening number on a program that would subsequently lead then, within the same day, to the Louvre, Montmartre, the Eiffel Tower, the Opéra, and the stores on Boulevard Haussmann.

Gérard pushed his cart loaded with cardboard boxes, stopping outside every side chapel. With a mechanical gesture, he would cut around the base of every box then lift the lid, revealing a stack of candles in the likeness of the Blessed Virgin Mary, which he would then immediately place in the tailor-made stands. Above the candle dispenser was written, in luminous letters and several languages: Help yourselves, the offering is at your discretion, suggested amount: 5 euros. Then, with an equally weary gesture, he would empty the neighboring metal racks where, the previous day, several hundred candles had burned down over the course of hours, giving way to a new row of night lights, prayers, and words of hope addressed to Mary. A little later, another member of staff would come and empty the collection boxes full of coins and banknotes into secure canvas sacks. There were similar stands with candles all over the cathedral, placed in strategic locations, at the foot of statues, beneath crucifixes, in chapels devoted to private prayer. The morning promised to be a long one, and the fifteen years that stood between him and retirement a long road paved with tens of thousands of cardboard boxes, each filled with candles in the likeness of the Blessed Virgin Mary.

Gérard sighed and resumed his round. Like every day for years now, Madame Pipi, invariably seated on the same chair next to the Virgin of the Pillar, invariably wearing her straw hat studded with red plastic flowers, invariably gave him a panic-stricken look and opened her mouth to say something to him. Like every day for years now, Madame Pipi thought better of it and, by way of conversation, crossed herself. With a little luck, she would leave Gérard the morning free to complete his round. Then, invariably, the old madwoman would end up falling asleep, and let a trickle of urine escape from under her, which would then have to be wiped away with a floor cloth.

A little farther, he greeted two cleaning women who were finishing sweeping the north transept, silenced a group of Chinese whose cackling echoed through the cathedral, which was otherwise still quiet at that time, then, pushing his cart, set off along the black and white tiled floor of the ambulatory. It was then that he remembered his colleague, the guard. Immediately, he saw her. Or rather, in the half light, he just made her out.

The bombshell was indeed there, at the very end of the ambulatory, perfectly still, alone, as though delicately placed on the bench outside the Notre-Dame-des-Sept-Douleurs chapel. Gérard approached and started emptying the nearest candle rack. The few candles lit by the first visitors of the day spread more shadow than light, so that what he was able to distinguish was a form rather than a body, a profile rather than a face. She was wearing a short white dress made of such thin fabric it followed closely every curve, every bend in her flesh. Her black hair, shimmering in places, cascaded over her neck and shoulders like a river of silk. Her hands, joined in prayer like those of a child, rested on her bare thighs. On her feet, held demurely together under the bench like those of a schoolgirl, she had a pair of high-heeled pumps so white and varnished they attracted attention and underlined her slender ankles and the contours of her calves.

Gérard lost himself in the contemplation of this stunning figure, forgetting for a moment his boxes of candles, his cart, his hassles, and the monotony of his work as sacristan. However, he was soon interrupted by the crackle of a radio, the one he wore at his belt, emitting his name.

“Guard to sacristan … Gérard? … Gérard, do you read me?”

“Yes, I can hear you. What do you want?”

“Have you been to see?”

“I’m right here.”

“Is she still there?”

“Yes. Good as gold.”

“And?”

“Definitely explosive … You were right.”

He put back his walkie-talkie with the guard’s laughter still resounding from it, then, as if with regret, finished cleaning out the candle rack. A handful of worshipers was already entering the chancel, where the nine o’clock mass was about to begin. He had to get the necessary liturgical accessories ready. Father Kern was officiating that morning, and Father Kern did not tolerate any delays.

A little later, he again had occasion to go through the ambulatory. An automatic dispenser of medals stamped with Ave Maria Gratia Plena had just become jammed and a tourist, a corpulent American woman, was tormenting the refund button. In the chancel, the mass followed its course. Father Kern was delivering the day’s homily in his metallic, authoritative voice, plunging the cathedral into a respectful silence. As he opened the cover of the medal dispenser and the jammed coins fell one by one as though from a money box, Gérard ventured a glance at the young woman dressed in white. She was there, she had not moved, her hands still clasped together on her pale thighs, her two pumps still united. Outside, the sun was rising straight up in line with the chapel and, penetrating through the stained glass in the East, was starting to bathe the young woman’s translucent face in a red and blue halo worthy of a Raphael Madonna. Motionless on her bench reserved for prayer, protected by a rope that isolated her from visitors and gave her the appearance of a holy relic, she stared at the statue of the Virgin of Seven Sorrows with an oddly vacant expression.

Gérard closed the medal dispenser and took a couple of steps toward the young woman in white, but the American tourist was already ahead of him. She took a banknote from her handbag and pushed it through the slit in the stand, then took four candles, which she lined up on the nearby rack before lighting them one by one. Their flickering light finally illuminated the girl’s face.

The tourist crossed herself and approached the bench. In a heavily-accented whisper, she asked the young woman in white if she could sit next to her in order to pray. Still motionless, the girl did not deign to reply, her eyes as though transfixed by the statue of Notre-Dame-des-Sept-Douleurs. After repeating her question and still not obtaining an answer, the American deposited her posterior on the bench, making the wood crack slightly beneath her weight. Then, as if in slow motion, as if in a nightmare from the dead of night, the white Madonna slowly shook her head. Her chin came down on her chest then, gently, almost gracefully, her whole body toppled forward before collapsing on the checkered tiles.

That was when the fat American woman started to scream.