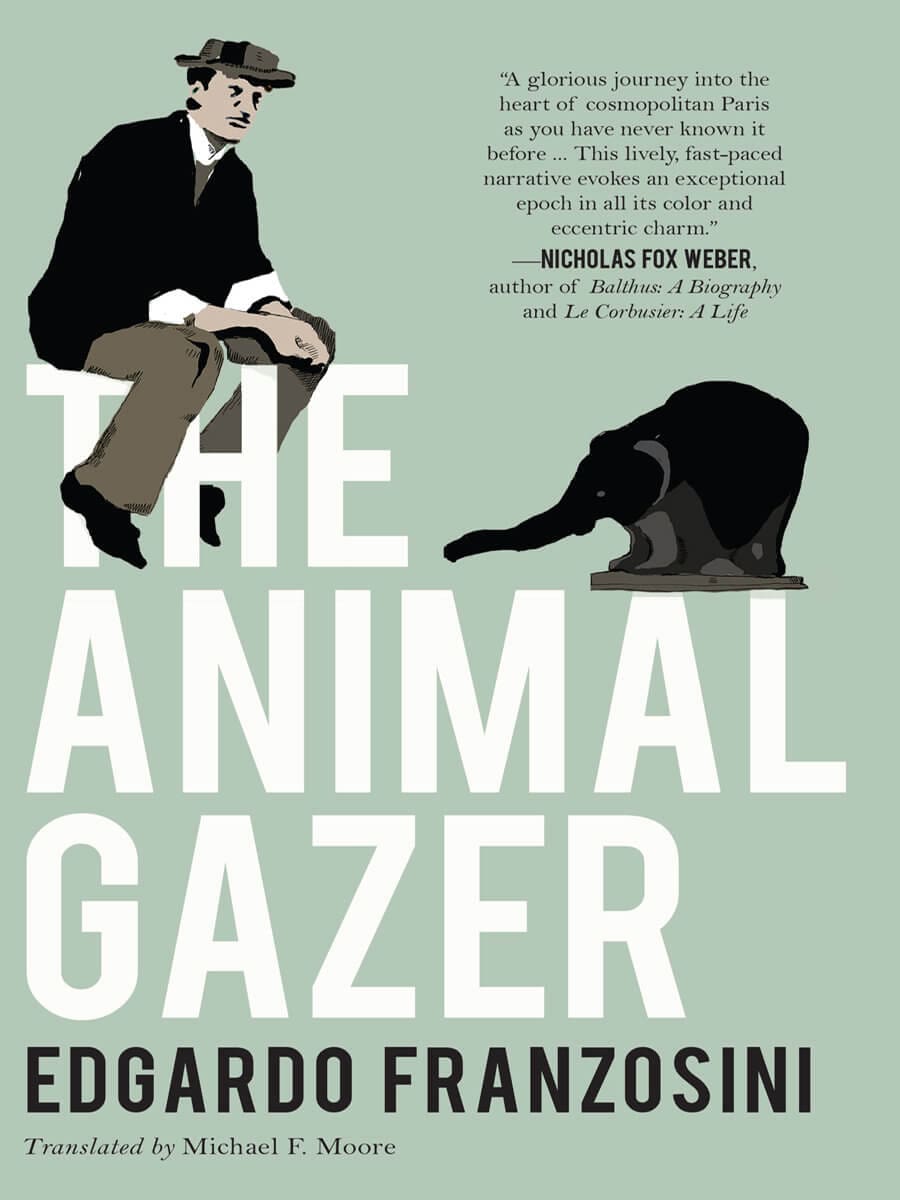

A hypnotic novel inspired by the strange and fascinating life of sculptor Rembrandt Bugatti, brother of the fabled automaker. With World War One closing in and the Belle Époque teetering to a close, Bugatti leaves his native Milan for Paris, where he encounters Rodin and casts his bronzes at the same foundry used by the French master. In Paris and then Antwerp, Bugatti obsessively observes and sculpts the baboons, giraffes and panthers in the municipal zoos, finding empathy with their plight, identifying with their life in captivity. As the Germans drop bombs over the Belgian city, the zoo authorities are forced to make a heart-wrenching decision about the fate of the caged animals, and Bugatti is stricken with grief from which he’ll never recover. Rembrandt Bugatti’s work, now being rediscovered, is displayed in major art museums around the world and routinely fetches large sums at auction. Edgardo Franzosini recreates the young artist’s life with intense lyricism, passion and sensitivity.

Excerpt from The Animal Gazer

By the main door of 3 Rue Joseph-Bara, a lead-gray building with a tile roof that had lost all its former elegance, Madame Soulimant, the concierge, was sitting, as usual. There, by the main door, she would spend most of the day—and in summer often some of the night as well—shifting her cane-bottomed chair from the right to the left of the small arched entrance, depending on the hour.

“Good morning, Monsieur Bugatti,” she said, turning to a man passing through the entrance.

The man replied courteously, doffing his wide-brimmed black felt hat, revealing a broad and prominent forehead. He was tall and elegantly dressed, but his shoulders were stooped and his gait stiff and awkward. (According to his friend André Salmon, when he walked he gave the impression of wanting to shun people if not avoid them altogether.)

“Can you believe this weather, good heavens! Not a very promising start for the fall!” said the concierge, huddling in a sheepskin shawl, dirty and yellow, that Madame Soulimant would drape over her shoulders at the first sign of cold weather. “I read in Le Matin that it’s the cannon shots, the artillery fire. That’s what’s causing the rain!”

“Really?” asked Rembrandt Bugatti.

“Yes, the influence of the cannons on the rain is as sure as the sway of the moon over the weather!” replied Madame Soulimant, with a slight turn of her head, her frizzy gray hair tied behind her neck in a loose bun.

Rembrandt also read the news of the war every day in the pages of Le Matin and Le Petit Journal. The week before one item in particular had caught his attention. The Siegesallee was a broad boulevard in Berlin lined by thirty-two monumental marble statues depicting the Margraves, the Prince Electors, the Dukes and Kings of Brandenburg and Prussia, and the ancestors and predecessors of Wilhelm II. At one end a wood and plaster totem had been raised bearing the same features as General Hindenburg. L’Illustration reported, “At night it is illuminated by three hundred torches and its shadow is projected down the entire length of the avenue. And to assure that the spirit of war and victory, ‘the sovereign with echoing arms,’ is on their side, the people of Berlin have been invited to stick at least one nail in the figure. It costs one hundred marks to insert one golden nail, thirty for a silver nail, and only one mark for steel.”

“And meanwhile,” added Madame Soulimant, “the Germans continue to advance. Soon they’ll be here.”

“Have you been to the market, Monsieur Bugatti?” the concierge asked the tenant, speaking a little louder so as to be heard.

Chronic otitis had made Rembrandt almost deaf. One year earlier he had started to feel painful spasms, whistling, humming and his own voice echoing in his ears. Sounds had all started to blur into a single drone. The only thing he could still distinguish were the sounds of animals—trumpeting, roaring, whinnying—at the thought of which he could not hold back a smile. A white liquid had started to ooze down his cheeks on occasion. An ailment of this type was still considered insignificant, almost healthy, as his doctor told him, but there could be many serious complications: meningitis, perforation of the carotid artery, cerebral hemorrhage. This is why, after administering him a compound of sulfate and sodium salts, the doctor prescribed hot compresses on the ear, fumigations, and gargling.

“Yes, first to Mass and then to market. You can’t find a thing there, you know. Four eggs and a crust of bread,” Bugatti replied. If not for a few overly guttural r’s, Bugatti’s French would have been perfect: by then the accents fell naturally on the right places. Besides, more than twelve years had gone by since he had left Milan and Italy and decided to split his time between France and Belgium, going back and forth: a few years in Paris, a few years in Antwerp.

“Don’t mention bread,” said Madame Soulimant, “the thought of it makes my tongue swell and gives me pains in the chest and kidneys . . . worst of all, forgive me for saying this, after eating bread I can’t stop burping.”

Rembrandt shrugged his shoulders.

On their way out to Rue Joseph-Bara, all kinds of people had passed through the entrance, which reeked of cabbage soup, turpentine, rancid ham, and urine.

And so many artists! as Madame Soulimant remarked with a certain pride. She had this to say about Paul Gaugin: I remember him, a big tall man. He was no brute, but he was always excited, talking in a loud voice, and he never closed the main door behind him. As for Jules Pascin: the only time he ever opened his mouth was to ask if the mail had arrived. Most of the time he was so drunk he could barely stand up. Is there a letter for me? he would ask on his way in or out. How annoying! Any postcards today, Madame Soulimant? A telegram, perhaps? In many long years no one ever sent him anything. An impudent conceited little Bulgarian. Nothing like you, Monsieur Bugatti.

Madame Soulimant liked this distinguished, reserved man with his angular face and serious expression. (Years later, seeing an actor at the cinema whom the French used to call Frigo but later became world famous as Buster Keaton, Madame Soulimant could not help but reminisce on the sad face of that tenant.)

“Well, have a good day,” said Bugatti.

“And a good day to you,” replied the concierge, placing her hands over her breast and lowering her gaze to the pointed black patent leather shoes with a brass monk strap that, despite the rain, Bugatti wore every day. He had on an overcoat that reached almost all the way to the ground. He opened it slightly to reach inside and dig out the apartment keys from a pocket in his black and white checked jacket, revealing a pair of rather wide gray corduroy trousers, almost puffy around the hips, which suddenly narrowed at the knee to end in a tube shape around the ankles.

What elegance, what refinement, thought the concierge. Only princes, marquises, or dukes dress this way, she thought. And it was no slip of the tongue, when she happened to speak to someone else about him, that she called him the Aristocrat. Monsieur Bugatti, the Aristocrat, is also an artist, a sculptor, she would tell people, but he never invites models up to his studio. That way she didn’t have to worry about anyone leaving muddy shoeprints on her stairs.