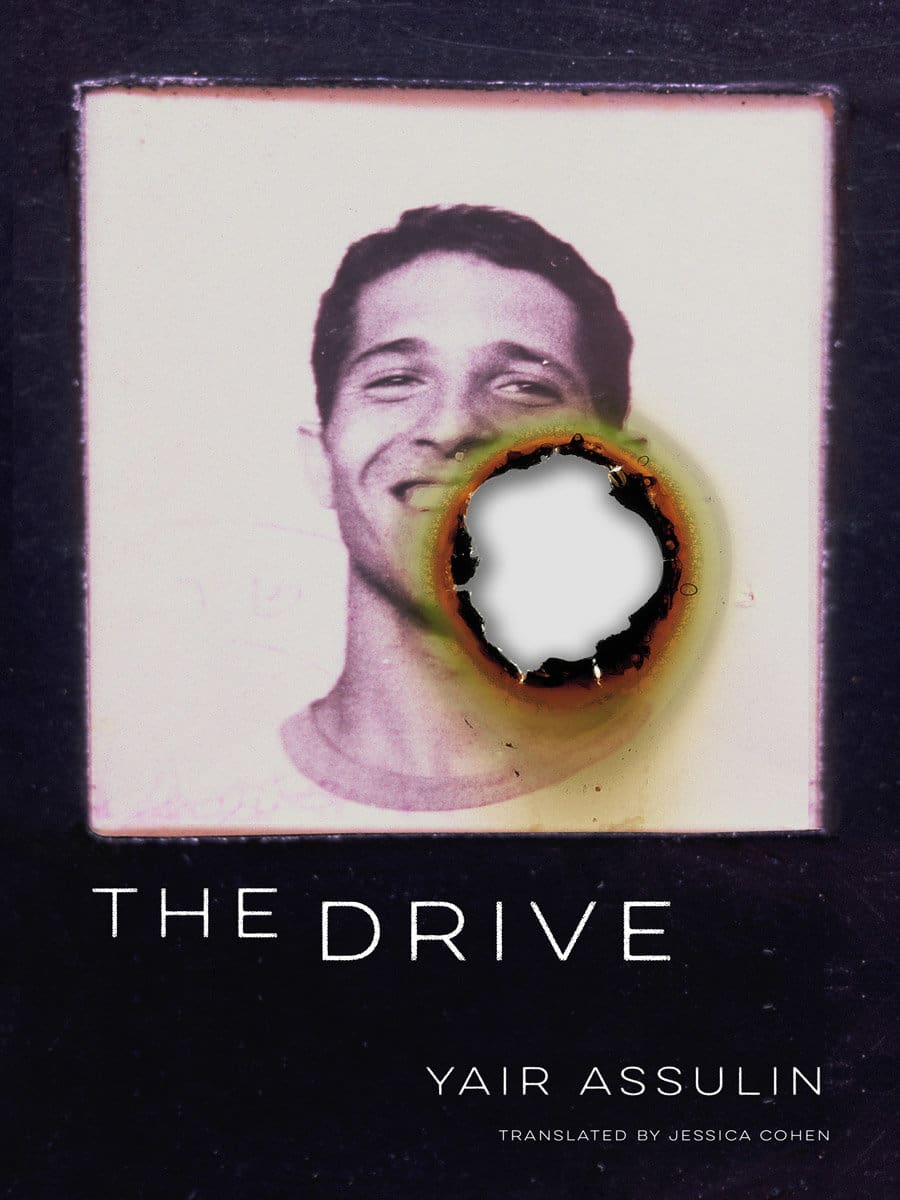

This searing novel tells the journey of a young Israeli soldier at the breaking point, unable to continue carrying out his military service, yet terrified of the consequences of leaving the army. As the soldier and his father embark on a lengthy drive to meet with a military psychiatrist, Yair Assulin penetrates the torn world of the hero, whose journey is not just that of a young man facing a crucial dilemma, but a tour of the soul and depths of Israeli society and of those everywhere who resist regimentation. Weary of being forced to be part of a larger collective, can one fulfill a yearning for an existence free of politics, the news cycle and the imperative of perpetual battle-readiness—without risking the respect of those we love most? A compelling story of an urgent personal quest to reconcile duty, expectations and individual instinct.

Author Yair Assulin, Booker Prize winning translator Jessica Cohen and novelist Ruby Namdar discuss The Drive in an online presentation co-sponsored by McNally Jackson Books in New York City and City Lights Booksellers in San Francisco. Click here to watch a video of the program.

Excerpt from The Drive

The car coasted along the empty highway to the Mental Health Officer at Tel Hashomer Hospital. “Tell me what you want,” Dad had said the night before, in tears, after I’d cried for perhaps an hour without stopping and said I couldn’t go on, that I felt as if I were suffocating, that I’d rather die than go back to the base. “Just tell me what you want,” he repeated, “what do you want to do? What do you want to happen?”

“I don’t know,” I answered. “I don’t know, I really don’t. I just know that I don’t want to go back there. I don’t want to.”

“But what is it that’s so terrible there?” he asked for the millionth time since I’d first cried over the phone, and I knew that someone looking from the outside could not even begin to comprehend the suffocation that filled me each time I took the train to the base, the insurmountable pain I felt when I walked through those gates, the fear of something I cannot describe or define, the horribly cramped sensation that was unrelated to anything, certainly not to a particular place or space. Again I told him that I was miserable. Again I told him that I felt I was losing myself. A few days earlier I’d told him I wanted to jump in front of oncoming traffic. I didn’t want to die, I just wanted some time off, a little time to calm down.

Now I remember that picture clearly, of how I stood on the side of the dilapidated road outside the base and there was mud everywhere. I remember the headlights of a distant car approaching, and the feeling that this time I was serious, this time I was really going to do it. I remember the voices in my head that told me I’d already said that so many times, and I remember the insistence in my mind that this time I had no choice, I was going to jump, and even if I died I didn’t care. Then I envisioned Mom and Dad’s faces, and I heard Mom’s voice, which had been slightly high-pitched when I’d called a few days or a week earlier and burst into tears when I said I couldn’t take it anymore.

I was on a different base then, near Nablus. The whole unit was on that base, which was full of tents and surrounded by giant concrete walls, long lines of massive gray blocks. I walked around for a week feeling as if I were going to suffocate. All I wanted to do was shut my eyes and sleep. It was winter and the work was exhausting: sitting in the war room listening to the phone. It wasn’t dangerous, I know, not dangerous like driving in the middle of the night in a black Audi to arrest a wanted person in a village, or like sitting at a lookout post in the middle of nowhere when someone could put a bullet through your head at any minute, or like actually fighting in Lebanon or Gaza. But for me, it was soul-crushing. It wasn’t just the work but all the people who hung around those big rooms full of telephones and supposedly important conversations, and the horrible feeling that you were insignificant. That you were nothing. That you were but one more instrument on the desk, like the pen or the computer or the old, encoded phones. Sometimes I had the feeling that I wasn’t even an instrument, that in fact I hardly existed, that I had to do everything for someone who did everything for someone who did everything for someone, and sometimes I had the feeling that the ladder never ended but merely branched out endlessly and reeked and grew mold and became caked with mud.

That was how I felt on that base, but I know that even that doesn’t explain the phone call when I could no longer suppress my sobs as soon as I heard my mother ask how I was. Up until then I kept trying to sound as if everything was fine, there was no problem, I was doing all right. And that definitely was not a reason I could give Dad when he asked me, “What’s so bad there?” Because even that didn’t explain why things were so bad for me there—not the reeking ladder that never ended or the fact that I wasn’t important and didn’t exist, not even the dreadful fact that I did not have my own regular bed on that base, that a few of us shared what was called a “whore bed,” and every morning I had to strip my sheets off and shove them under the bunk bed in the big green dusty bag we were given at the induction center. Or that after a night shift I had to wait for someone to get up so that I could get some sleep until they came to wake me up and tell me I’d slept enough, or in fact not even wake me, because I was usually awake already and lying in bed with my eyes closed just to steal a few more moments of quiet, a few seconds in which I could think about Ayala, for example, and remember how a few weeks ago we’d had a wonderful conversation after we hadn’t talked for a while, or to think about the argument I’d had with Dror and about how I was right—to reanalyze the logic of my position and verify that I really was right. That was probably also not the reason for the phone call that dropped us into the whirlwind that eventually saved my life.

And yes, I know that every soldier goes through similar things at one time or another, and there are some who go through much worse, and there are even some who are going through similar things right now, as I write these words in a quiet room, with a Schubert sonata for violin and piano playing in the background. But when your soul hurts—and in those days it hurt more than I had ever imagined it could, and it kept on hurting more and more—all this knowledge about other people and other pain makes no difference and offers no relief.