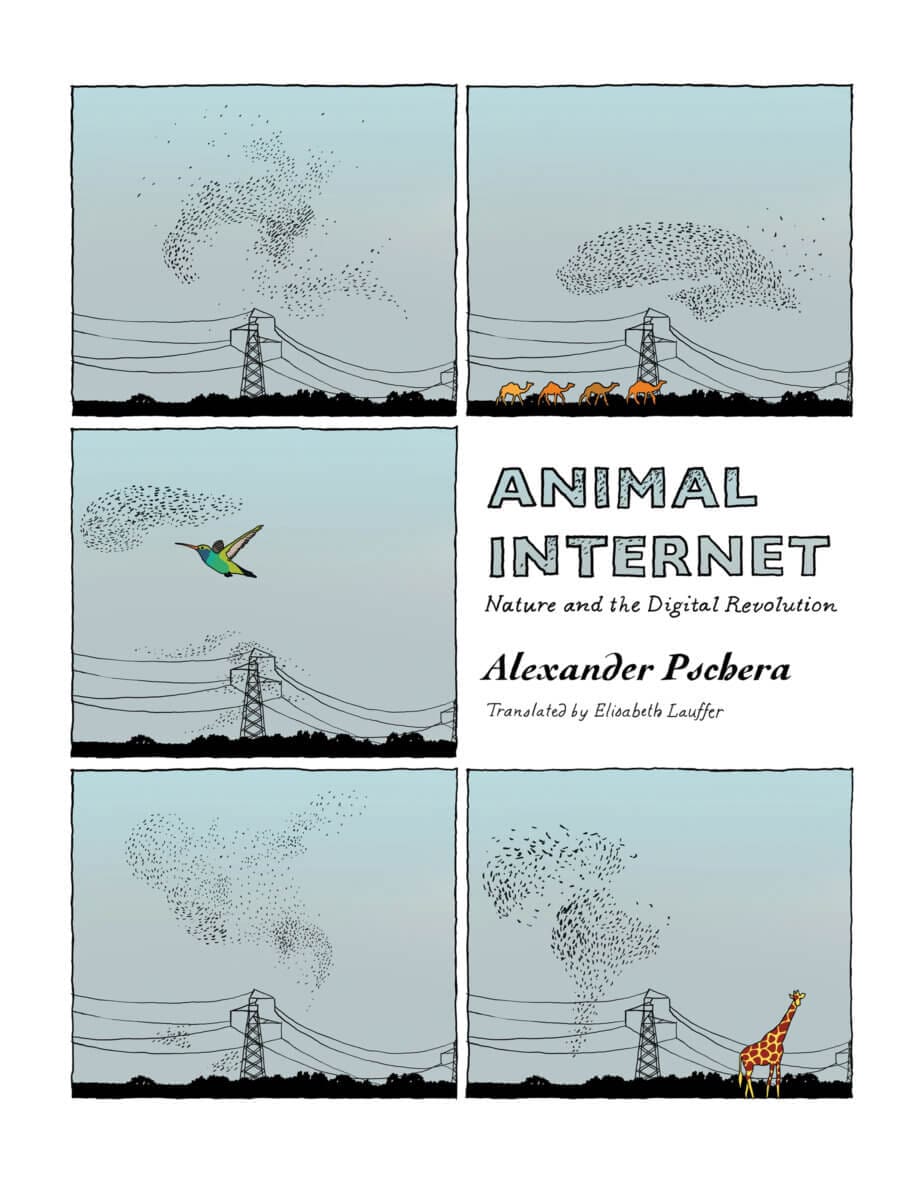

A bestial Brave New World is on the horizon: Some 50,000 creatures around the globe—including whales, leopards, flamingoes, bats and snails—are being equipped with digital tracking devices. The data gathered and studied by major scientific institutes about their behavior will not only aid in conservation efforts and warn us about tsunamis, earthquakes and volcanic eruptions, but radically transform our relationship to the natural world. With a broad cultural and historical lens, this book examines human ties with animals, from domestic pets to the soaring popularity of bird watching and kitten images on the Web. Will millennia of exploration soon be reduced to experiencing wilderness via smartphone? Contrary to pessimistic fears, author Alexander Pschera sees the Internet as creating a historic opportunity for a new dialogue between man and nature.

Foreword by Martin Wikelski, Director, Max Planck Institute for Ornithology. The book includes eight color photos and an index.

Excerpted in Scientific American magazine.

Excerpt from Animal Internet

Introduction: Why Today’s Little Red Riding Hood Has a Smartphone in Her Basket

An Old Story in a New Light

Little Red Riding Hood is relieved. She finally has an iPhone now, too. Sure, her mother said she’s still a bit young, and her grades need to improve if she wants to keep this privilege, but the pressure from her clique is simply too great. All her friends have one, and one certainly doesn’t want the girl to become an outsider.

Little Red Riding Hood’s mother is a single parent, and she’s at work all day. She figures it’s not such a bad thing for her to know where her child is. Especially since Grandmother moved to that lonely house on the outskirts of town, where Little Red Riding Hood goes most days after school for some adult supervision while she does her homework. The path she has to take goes through some woods that Mom isn’t crazy about. She likes that she can get in touch with Little Red Riding Hood, and that her daughter will send her a text every now and then. Mom is also constantly reminding her to take out her headphones when she’s in the woods, in order to hear what’s going on around her. You never know who might be hanging around there.

But Little Red Riding Hood isn’t afraid of the woods, let alone the animals that live in them. She loves the doe, the stags, the fox, and the hare. Every day she discovers something new—usually off the path—which is why she also usually gets to Grandmother’s late. But that’s not a problem, because when she tells Grandmother about her new discoveries, the old woman beams with joy. For Little Red Riding Hood, animal tracks and birdcalls are messages from friends. Even the wistful “dieu-dieu-dieu” of the bullfinch quickens her heart, and when she sets out toward home at dusk, the intriguing “who – who – who are you?” of the tawny owl doesn’t sound like a threat, but an invitation. It is the call of nature, and Little Red Riding Hood is more than happy to listen.

What her mother doesn’t know is that this is the very reason she wanted the iPhone. She is as indifferent to texting with her friends as she is to watching those pointless music videos. But all the nature apps out there have given her an entirely new perspective on the woods. Not only can she better identify birdcalls and read animal tracks. Since downloading Animal Tracker onto her phone, she now knows that Martha, the vixen living in the den near the clearing in front of Grandmother’s house, has four pups. She also knows that the red kite that nests in the spruce at the edge of the clearing struck a different course in returning from its winter home this year. And most important, she knows that a beautiful, big gray wolf has been hanging around the area for days. He comes from a pack along the frontier between Germany and Poland, not far from Little Red Riding Hood’s home, and his name is Ferdinand. Ferdinand the Gray, as she secretly calls him, has a GPS tracking device that allows his every move to be followed. What he looks like, what he weighs, which pack he’s running with, how many children he has, and everything he’s experienced on his forays—Little Red Riding Hood can read up on all of this using her Animal Tracker account. A green dot on the map shows Ferdinand’s current position. She trembles at the sight of him approaching a main road or the interstate, and always hopes that he’ll find a safe route into the nearest woods.

This afternoon, Little Red Riding Hood is atremble once more. Not with fear, but with joy. Because Ferdinand’s green dot has appeared on her GPS display and is approaching the red mark that indicates her position. He moves closer and closer. Fingers shaking, she zooms in. Her heart leaps: it can’t be more than a few hundred yards separating her from Ferdinand. She carefully looks around. Straight ahead is a meadow, beyond that the woods retreat into darkness. Little Red Riding Hood sets down her backpack and hides behind a mossy tree. She opens the video app on her iPhone and waits. Maybe she’ll manage to get some footage. Her breathing grows shallow, and she has to try hard to keep her hand still. Minutes pass, but it feels like hours. Her courage is flagging when she spots a mighty gray shadow moving out of the thicket. A majestic wolf’s head appears, frozen in place for a few seconds. Ferdinand the Gray! He assesses the situation in the clearing; it almost looks like he’s trying to hear something, himself—hopefully he doesn’t sense Little Red Riding Hood. The girl starts recording. Now the animal moves. Slowly, but decidedly, the wolf crosses the meadow. He is moving straight toward Little Red Riding Hood.

The video is running. Two minutes. Two minutes, thirty seconds. Three minutes. Little Red Riding Hood gets a cramp in her leg, but there’s no time for the pain. The wolf is now barely twenty yards away. She appreciatively moves the camera along the animal’s body—she films his head, back, and bushy tail. The wolf stands still and looks directly into her lens. Has he discovered her? For a fraction of a second, memories of old fairy tales flash through Little Red Riding Hood’s mind, images of small, helpless girls deep in the shadowy wood, threatened and devoured by savage wolves. Could there be any truth behind those tales? She thinks of her single mother. “What would she do without me?” For a moment, our uneasy observer considers stopping the video and calling the emergency number.

But it doesn’t even occur to Ferdinand the Gray to play into the myth humans have created for him. A warm sunbeam spans the meadow. Steam rises from the grass. The old wolf stretches out his front legs. He yawns with relish and flops onto the grass like a sack of potatoes. Little Red Riding Hood keeps filming and filming. Already five minutes, thirty seconds. What would happen, anyway, if she left her hiding spot and approached the wolf? Would he attack? Or would he simply flee? Suddenly she’s tempted to risk the experiment, but reason ultimately prevails. There also isn’t time. She’s already running over half an hour late, and Grandmother must be waiting for her.

At this very moment, a shrill “beep beep beep” announces the arrival of a text message. Her mother! “where r u … call me right away … im worried … mom” The digital tone shoots through the woodland idyll like a deadly arrow. Ferdinand the Gray jumps up and disappears into the trees like greased lightning. Little Red Riding Hood can just barely follow the green dot on her screen, which is moving faster and farther away from the red one. “Farewell, dear friend!” she whispers. “Take care!”

Her wolf video is six minutes, twenty-four seconds long. No sooner does she arrive at the house than she shows it to her grandmother, who watches eagerly. Together, grandmother and granddaughter watch and rewatch the amazingly sharp images. Little Red Riding Hood can’t get enough of recounting the feelings that alternately overcame her, crouched behind that weathered old tree stump: tension, excitement, fear, joy. She suddenly remembers the cramp in her left leg, too. She then uploads the video onto Ferdinand the Gray’s Facebook page. The page was created by wolf fans to document the animal’s life. The old fellow’s got over two thousand digital friends—not bad for such a supposed villain! So far, though, the site hasn’t had much more to offer than blurry pictures and tracking updates. Little Red Riding Hood’s video is the first long documentation—and the comments left by the wolf community are accordingly enthusiastic. They range from “Fantastic footage, I would have been so scared in your shoes!” to “Forget National Geographic—watch Little Red Riding Hood.” Within hours, the video has over five thousand clicks and no end of shares. It finds its way to the World Wildlife Fund and the Natural Resources Defense Council homepages.

Little Red Riding Hood ends up spending the night at Grandmother’s house. They drink green smoothies—Grandma is a modern woman, and a vegan, at that. By the time Little Red Riding Hood finally manages to break away from Ferdinand the Gray, it’s already pitch-dark. Even the bullfinch has ceased his somber “dieu-dieu-dieu” and tucked his head into his red-gray plumage. Before Little Red Riding Hood pulls the blanket over her own head, she takes out her smartphone one last time, to say goodnight to Ferdinand. And then she sends her mom a text: “hi mom … i made an amazing new friend … his name is ferdinand … tell u about it tmrw … he may be a lot older than me, but he’s so beautiful … but ur the best, always have been, always will be … luv u … lil red.”

This story could occur, with slight variations perhaps, in much of Europe and North America today. It is only slightly too perfect. The new version of Little Red Riding Hood is no fantasy. It really does exist, this direct connection between human and animal. I have the evidence to prove it: the ultraflat smartphone in my pocket connects me to a flock of glossy blackbirds that spend their summers in Bavaria and their winters in Tuscany: the northern bald ibis, or waldrapp. Software installed on my phone establishes contact with these rare and beautiful birds as they fly in striking V-formation over the Alps for the winter. Many dangers lurk along their voyage over the mountains. This is also why the waldrapp is tagged with a radio transmitter, which allows its handlers to locate and thereby better protect it. The bird’s last “encounter” with humans proved considerably less symbiotic. The waldrapp was hunted so aggressively in past centuries that it nearly went extinct, with very few remaining in the wild. Now a reintroduction program is under way, using technology in an effort to bring the bird back home to Germany. The positioning data for individual birds are transmitted via satellite to a database, and from there to a Facebook page, where the information is presented in text, image, and video formats. Facebook is thus transformed into an animal blog. This is a space where the birds—and not just some anonymous representatives of the species, either, but the waldrapp ibises Balthazar and Remus, Tara and Pepe—can share the literal ups and downs of their lives. Using digital technology today, I can get as close to the waldrapp as Little Red Riding Hood got to the wolf, or as the prehistoric hunter had to get to his prey, in order to kill it. The Internet is anything but virtual and abstract here; it is a hyperreal, sensory experience. I can see where the ibises currently are and what they are doing. I can see what company they are keeping. I can see what problems they are combating: whether they have flown into a snowstorm or been blown off course, and how they respond, in an effort to get out of trouble.

A chapter in the history of human-animal relationships has thus come full circle. The hunter of the Stone Age had to come within a spear’s throw of the mammoth. He heard the animal’s breath and smelled its excretions. Later, the development of better weapons for hunting marked the end of this existential proximity to the wild. It was stored, however, in humans’ cultural memory, in the form of fables, myths, and fairy tales, in which frog princes and cat courtiers, foxes and rabbits came into regular contact with humans and one another. After centuries of alienation, humans can now regain this closeness. It is possible to gain a bird’s-eye view of the world, flying—like a postmodern fairy tale character—over the ridges of the Dolomites on the back of a waldrapp. We are getting back to our roots culturally, as well. In the grottos of Altamira, the hunter painted mighty animals in earth tones on stone, images that still bear witness to the deep relationship between humans and animals, the hunter and the hunted. My mammoth is a waldrapp ibis that I, along with many others, worship on a Facebook page. These birders comment on incidents that occur during migration and upload their own photos. The digital Facebook wall and the Caves of Altamira are, as surprising as it may sound, two sides of the same coin. Both fulfill the same role in the systems of their respective civilizations. They visualize the awareness we have of nature, thereby strengthening a mutually shared value system.

We are standing on the threshold of a new era of interaction with and awareness of nature, because the waldrapp is no anomaly. There are many further examples of the digital interconnectedness of humans and animals. In the Cascade Mountains of Oregon or on Arizona’s Kaibub Plateau, Little Red Riding Hood’s encounter with the wolf could become an everyday occurrence—with a better outcome for the animal and without traumatizing the human. Many of the wolves ranging the American countryside, disquieting humans along the way, are wearing GPS collars. Their positioning data are recorded and then transferred to websites, where anyone can follow the animals. In addition, photos captured by hidden cameras provide a vivid take on life in the wolf den. These wolves are no longer anonymous beasts that appear out of nowhere, attack, then vanish in the mist. Instead, they have names and personal histories. They are no longer simply representatives of a species, but rather, real individuals. We can research their biographies and personal preferences as easily as their personalities and social behavior. This ultimately transforms wolves into likable contemporaries—a remarkable career for the creatures, which have for centuries been pegged as humans’ archenemies. They have been considered sneaky, sly, ferocious. This new surveillance technology succeeds where generations of ardent eco-advocates and eager ecological educators failed—in freeing the wolf from the snare of misrepresentation and allowing it to turn back into a normal animal. Thanks to digital advances, its daily life has been made transparent and tangible. A new dialogue between humans and nature has arisen. To take this dialogue a step further, it would not be unrealistic to dream of a new language between humans and animals.

But why, some might ask, do we need such a language? Don’t we do enough already to research animals’ habitats and ensure their survival? Doesn’t the conservation debate already get considerable attention in politics, society, and the media? Isn’t it even safe to say there’s an overabundance of green issues today? It may seem that way subjectively, but in fact, despite a host of international programs, species extinction worldwide is not only advancing unchecked, it is rapidly gaining speed. Human and animal destinies are diverging, humans sitting on the Raft of Medusa, animals floating away on Noah’s Ark. The separation has become fundamental. Not only is the basis of many wild animals’ existence under threat, but these animals no longer play a role in everyday life, either, having disappeared from regular human routine in Europe and North America over the course of the last two hundred years. In many parts of Asia and Africa, where industrialization has not yet destroyed all native life forms, animals—both wild and working—still serve as companions to humans, sharing in their daily lives, while in the European cultural realm, they were forever supplanted by machines and technical apparatuses from the start of the twentieth century. The key factor, however, is that since then, humans and animals have occupied not only different living spaces, but different spaces of being—spaces that were formerly one and the same.

But the connection to nature, to that which grows, is inherent to humans, who are and always will be biophilic creatures. Humans cannot live without animals and plants. Hence the green compensation that has followed the years of nature deprivation and loss. Over the last two hundred years, the real animals have been replaced by likenesses. The process is dialectical: the further we distance ourselves from nature, the more we produce, reproduce, and disseminate images of animals—all without moving a single step closer to nature in the process. Postmodern awareness of nature simulates green structures and represents animals merely by pictures, or pictures of pictures, or links to pictures. But these representations do not replace the animals; instead, they simply fake their presence. This awareness has no way of accessing the tangible animal existence on display in the Caves of Altamira.

Nevertheless: overcivilized humans still hear the call of nature. Something profoundly authentic awakens in them when they drive out to the country or read about humans and animals in fairy tales and myths. Even the postmodern awareness of images appears to have an emotional center that responds to the call of the wild. The first questions to emerge: Why is this the case? How can that be? Next question: How can humans respond to this call? Because personal willingness is not enough to break free of the “idea of the idea of nature,” the cold prison cell in which the postmodern citizen has been trapped.

Technology, which first brought about and subsequently heightened humans’ alienation from nature, is now part of the solution. It is the missing link to reestablishing the connection to the animal kingdom. The Animal Internet has the potential to revive the human-animal relationship, thereby reinventing nature, as it were.

Despite hopes for a newfound closeness, it is worth considering that the shape of nature will face radical change in achieving this relationship. The chaos of wilderness will morph into a networked room. The thicket will be digitally cleared. Nature, defined as the untouched in the Western imagination, will not only be touched, but penetrated. If the postmodern natural world served as the temple of that ersatz religion called ecology, then the natural world remaining after this era will be a desecrated, denuded one. In becoming this transparent, however, nature loses a central quality: nature that is fully transparent is no longer autonomous. This iteration of nature no longer draws its authority from its independence vis-à-vis human society, but rather from its ties to the very same. The Animal Internet is turning nature into a system controlled, if not created, by humans.

This is a watershed in the consciousness of civilization’s weary ranks. Nature’s increasing illumination and transparency signifies the destruction of a space that has always served as a subjective escape route for the senses. Because in the last few decades, “back to nature” was the last possible antithesis—both politically and individually speaking—to the unrelenting rhythm of the economy and the working world. “Nature” was the last possible stand against the daily grind, perhaps even against what used to be known as “destiny.” For many, nature has even replaced God. This nature is now subject to the dictates of the all-consuming Internet. It is being materialized, no longer serving as an idea that can be readily used in opposition to the societal status quo.

The ubiquitous debate about transparency in data gains a significant aspect in connection to the Animal Internet. Today nearly fifty thousand wild, largely migratory animals are equipped with GPS units that transmit a constant stream of wide-ranging data. New animals are hooked up to the circuit every day. Huge amounts of animal data emerge—big animal data, so to speak. Till now, the big data debate has revolved around the questions of how much transparency we want and how people can protect themselves against monitoring by corporations and government entities. This discussion is now beginning with regard to the animal kingdom. Animals are now joining humans in the glass house. Bit by bit, a transparent natural world will emerge—animals are already becoming more easily tracked, cameras with self-timers send pictures from the farthest corners of the rainforest to users’ phones; Facebook pages and blogs provide information on animals’ whereabouts; smartphone apps reveal the location of highly endangered species like mountain gorillas or orangutans. This revolutionary form of interaction with animals will yield a new, as yet unknown and extremely sensitive store of data available to anyone who owns a computer or smartphone. With this knowledge, humans will push their way deep into the lives of animals; they will break open their “personal space.” Against the backdrop of the data debate about the omnipotence of Internet companies and people’s vanishing freedoms, the prospect of a transparent nature seems like an expansion of the digital war zone. Do we need data protection for animals? The question arises in a genuine debate about the new friendship between humans and animals.

Furthermore, this is necessary because transparent nature introduces a new way of ecological thinking that breaks with conventional ideas and practices of nature conservancy. Transparent nature is no longer a habitat in isolation; rather, it is a green habitat embedded in a gray civilization, the two connected by digital paths, bridges, and tunnels. The central idea of transparent nature is the direct, albeit technologically driven, contact that is again possible between humans and animals. The precondition for this is humans’ ability to move freely in the natural world. Habitats and nature preserves, those instruments of classic ecology, function differently. Their objective is not to encourage contact, but to prohibit it. They abide by the principle of systematically barring human access to nature, as opposed to seeing it embedded in their everyday life. Habitats try to save animals from humans. This is reasonable, of course, but it also results in the impassable, ever deepening rift between humankind and nature. Humans are experiencing an estrangement from their natural surroundings, especially from animals. This romantic ecology of exclusion, as one might describe the philosophy of the habitat, attempts to further cast nature as an autonomous space, treating it as if it were exempt from the human-powered dynamic of global development. The central ecological question at the start of the twenty-first century, however, is this: How can humans save the environment without compromising their own future development? How can nature, with the help of technology, figure into the logic of human progress in such a way that both profit?

Humans can save the environment and animals from impending ruin only once they divorce themselves from the conception of technology and nature, civilization and wilderness, as competing or dichotomous spheres. This thinking defines current ecological thinking and concrete conservation practices. Beyond that, however, we must distance ourselves from the myth of an unspoiled, impenetrable natural world that answers only to itself, and acquaint ourselves with the idea of transparency in nature, as fitting to the age of humans. Humans are (inter)connected to animals in a new way in this open nature, and far from being punished for entering this world, they are rewarded. Technology is no longer the eternal adversary of nature, enemy of the righteous and engine of destruction; instead, it has emerged as an ideal, adaptable interface between humans and their natural surroundings.

This book proposes that such radical rethinking is the only way to save the animals. Not because this would automatically result in improved living conditions for them, but because it would teach humans to see animals anew, sensitizing them to their fate. For humans will want to save only what they know. Ecology needs to be restored to its essence: to the tangible relationship between humans and wild animals, which will serve as the foundation for whatever follows. Only a new form of communication can reconnect humans and animals. People today are more focused on developments that directly improve their own lives than on, say, a conservation program for poison dart frogs in Costa Rica. This book suggests a different course. It tells the story of that disruptive moment in technology, when the investment banker in New York or Frankfurt forgets about his new Porsche for just a moment and becomes online friends with a frog.