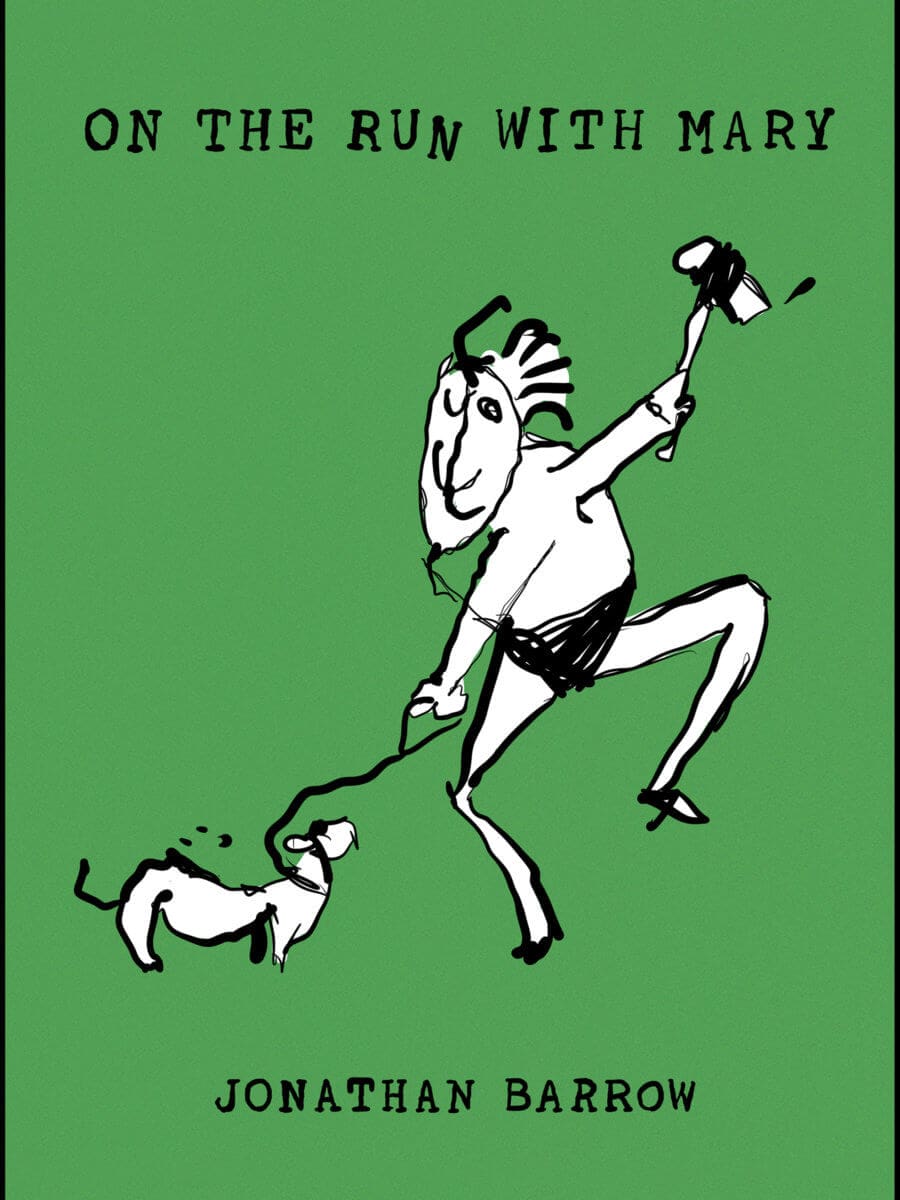

Shining moments of tender beauty punctuate this story of a youth on the run after escaping from an elite English boarding school. At London’s Euston Station, the narrator meets a talking dachshund named Mary and together they’re off on escapades through posh Mayfair streets and jaunts in a Rolls-Royce. But the youth soon realizes that the seemingly sweet dog is a handful; an alcoholic, nymphomaniac, drug-addicted mess who can’t stay out of pubs or off the dance floor. In a world of abusive headmasters and other predators, the erotically omnivorous youth discovers that true friends are never needed more than on the mean streets of 1960s London, as he tries to save his beloved Mary from herself. On the Run with Mary mirrors the horrors and the joys of the terrible 20th century. Jonathan Barrow’s original drawings accompany the text.

Excerpt from On the Run with Mary

| It is a strange dark evening with yellow skies. Rain falls and the rush-hour crowds begin to run for their stations.

There is a long queue. We sit patiently and an aide brings tea and warm buns. Next to me sits, all alone, a grievously injured rat. He had damaged his foot in a culvert and had walked four miles to find the hospital. Beyond us, I saw moles, hedgehogs, bats, flies, goats, cats, stoats, shrews and dormice . . . Many were in great pain and many passed away before our eyes. I mask Mary’s eyes with a cloth: these are things which a dog of her sensitivity should never see. Suddenly a most terrible howling from the casualty entrance. I watch closely as a badger, pouring blood, is lifted out of an ambulance. Apparently he had been involved in a collision with an articulated waggon on the A33. Upstairs, I wander through the operating theatres and see many dumb creatures suffering terrible indignities. In Theatre 6 a donkey is having a limb amputated, and next door I see a mole having his tonsils removed without proper anaesthetic. In Theatre 9, a hedgehog is having a prostate operation and all his prickles have had to be removed. That morning, the hospital had received a priority cable from Rhodesia. It warned them that a toad was arriving on Flight 4527 at 10.35 (Heathrow). The toad was dangerously ill and unless treated with the rare serum Ascusi Conci he would almost certainly lose his life. A general alert was sent to police at Heathrow. A special pass was issued to enable the toad and his handler to avoid customs and baggage check-out. The ambulance drove onto the concrete and, with siren wailing, and 6 police outriders as an escort, journey time to the hospital was just 15 minutes. Unfortunately he was found to be dead on arrival and his still warm body will be returned to Nairobi on a scheduled 707 tomorrow morning. After queueing for two hours I at last hear Mary’s name called over the Tannoy system. I take her to the surgery and place her on a low padded stool . . . Suddenly there is a panic in the passage and I hear rushing feet. Three orderlies burst into the room with a tabby-cat. She had taken an overdose and has been rushed to the hospital from her Hyde Park Gardens flat. The doctor orders a nurse to fetch the stomach pump. Just then, there is another sound of scurrying feet in the corridor. Without knocking, an orderly runs in with a barn owl in his hands. She had been found with her head in a gas oven and had been rushed to the hospital by taxi. Mary waits patiently. At last she is again summoned to the padded stool and the doctor, producing a stethoscope, rolls her on one side. He taps her here and there with a rubber hammer and listens carefully to her beating heart. He opens her eyes wide and inspects her teeth. He asks for a small urine sample and passes Mary a flask. But she is unable to produce anything and I have to apologise. When Mary is out of sight, the doctor asks me her history. I explain that we struck up an acquaintanceship on Euston Station concourse only that morning and that I understood she was out of work. The doctor diagnosed neglect and poor nutrition. He gave me a yellow slip which I was to take at once to the all-night chemist at Piccadilly Circus. On the way out of the hospital, a terrier was rushed past us on a stretcher. He had tried to take his life by leaping off Waterloo Bridge but had been fished out of the Thames by the river police.

***

The walk to Piccadilly was uphill and I stopped constantly for rests. Luckily, in Metton St., a kindly Rolls Royce driver stopped and offered me a lift. He lowered his electric window and asked where I would like to go. I was about to step in when Mary coughed and showed her head through a slit in my gaberdine. The driver spotted her at once and said he detested dogs. I must not travel with her. He insisted that I should leave Mary in the gutter where she belonged. Then Mary began to cry and the driver, hearing her sobs and seeing her poor matted coat, relented and gave her a cushion for the back seat.I was asked to sit up front along side him. After a few minutes I realized that he was a homosexualist. Though in his 70th year his trousers were extraordinarily tight around the crotch and his testicles protruded in an unpleasant fashion. Without warning, he put his hand on my thigh and began to stroke. And then he began at my fly-buttons. I had to look the other way. Mary was comfortable in the back seat. She was snoring a little and the tears had gone.Suddenly the car began to spin. The homosexualist had devoted too much of his attention to my pubic areas and had neglected the highway. Now we were facing oncoming traffic and a collision seemed inevitable. I saw the front of a truck and the driver letting go of the wheel and covering his face . . . I was told that the queer died on the way to St. George’s. There, in the mortuary, he was identified as Marcus Peimenne. They took off his silk clothing and put them in a dump bin. He had no next-of-kin and lived alone in Stafford Street. I was pinned under a panel and TD 3728 of the Metropolitan Police knelt beside me. He had taken off his tunic top and this was on my stomach. I tried to feel down but he guided my hand away. In the distance the sirens were wailing louder. They set up a plasma-drip on the roadside and a crowd gathered. ‘Jean, there’s a lad dying down there. Don’t let the children see.’ I heard the firemen with their cutters and later felt stretcher men wrap me in red blankets. ‘Is that lad dead?’ Then they pulled a strap (or girth) around my waist to prevent me rolling during the journey. I saw them wheel a heavy oxygen breather towards me. Mary could not get up the folding steps and a stretcher bearer, realizing we were acquainted, lifted her. She found the polished flooring tiles in the ambulance slippery and fell several times. Then the stretcher bearer placed her beside me. Immediately she licked at my blood with her rough tongue and found her way beneath the blankets. But the stretcher man, fearing infection, lifted her away. Above me the blue flashing light shone through the open ventilation slot, and the siren, deafeningly loud, made my ears hum. When the morphine began to act, I felt better and began to pick out the well-known landmarks beyond the smoked glass. But then the ambulance stopped violently. The curved doors were opened and my drivers began collaborating over their A-to-Z. We were hopelessly lost in some sort of cobbled alley. Hens’ feathers flew about and there was a stench of fowls’ innards. It was a poultry abattoir. There were hundreds of crated dead. My drivers lifted me down onto the cobbles. And there I lay, under the red blankets, looking up at the evening sky. Mary, tired and ailing herself, was asleep beside me. Then the stretcher men walked away. Sparrows, chaffinches, crows, rooks, blue-tits, thrushes and larks circled over me. Then a heavy flapping of wings: it was a Golden Eagle staring at me from behind a parapet. He swooped and I felt sick and faint. Luckily, a passing charabanc backfired and distracted him. My blood had stuck to the stretcher canvas. So, as I got to my feet, skin was torn from my groin and thighs. There were dressings and ointment in the ambulance and I did what I could. They had left the blue light flashing: it was reflecting in windows all down the alley. I could not find Mary. I searched up and down the alley. Then I heard a noise beyond an open door. It lead into the plucking room of the abattoir. There were 2,000 live broilers ready for tomorrow’s slaughter. Mary had got one by the leg. The bird was in agony and there was a deep wound in her breast. She screamed and blood poured from her mouth. Then pandemonium broke out. For in the next hutch there were 500 18lb turkeys. Furious at Mary’s brutality they had broken through their shutters and were white with anger. Hundreds of beaks began to peck at her and it was only my quick reaction which saved her from a terrible death . . . I took her in my arms and staggered as fast as my injured legs could manage to the main road. I looked back and saw the ambulance and stretcher surrounded by thousands of furious fowls. There were pheasants, partridges, Rhode Island Reds, and, then, with an alarming screech, another consignment of hens broke their hutch and poured out into the alley. Mary, shaking with fear, apologised for her behaviour and promised that it would never happen again. Suddenly I begin to pee uncontrollably. It must be caused by shock and I am deeply ashamed. In moments, my trousers are drenched and unsightly. I have to wrap my mackintosh tight to hide all trace. Desperate to do more, I run to the GENTLEMEN sign that I see 200 yards ahead. The attendant will not permit Mary to enter a cubicle with me and insists that she should be left in his booth. I take four rough towels from the pile and run to the end cubicle. In there, I stripped and dried myself. Suddenly there is a knock at the door. Foolishly, I open it and the attendant pushes his way in. He produces his organ and asks if I would like to be dirty with him. Disgusted, I push him away. He leaves at once and a minute later he passed a brief apology note under the door. I acknowledge this at once and I hear him snatch up my note and run to his booth. I am disturbed from my defecation by a coughing and snuffling in the next cubicle. It is strangely familiar. I go down on my knees and, placing my head as close to the gap as I dare, I try to see who it is. Horrified, I leap to my feet . . . for there, watching me through a spy-hole, is the Head Master. In a desperate panic, I try to get my clothes on – but find that he has cleverly hooked away my trousers and pants. I hear him smirking and grunting and a moment later he tosses a mountaineer’s grappling-hook into my cubicle. I crouch in the corner and watch helplessly as he scales the partition. For a moment I think he will lose his balance, but he finds a narrow ledge and hangs from it, kicking at me with his studded brogues. I am at my wit’s end and call desperately for the attendant. He comes running and, grasping the situation in seconds, he produces a revolver and fires several shots at the Head Master’s wrists. With a horrible scream, he loses his grip and falls headlong into the lavatory bowl. It is still full of my motions and he splutters and begs for mercy. But I have nothing to say to him and, after dressing, pull the chain. He cannot move for his head is jammed firmly in the bowl, and he suffers appalling indignities. Later I hear that he was rushed to St. Thomas’s with asphyxiation and deep wrist wounds. Once more, I try to make my way to Piccadilly to buy Mary’s tablets. She is rapidly sickening and her temperature and pulse-rate alarm me. She stumbles constantly and I carry her for the last mile. There is a long queue at the prescription counter and there are at least 70 in front of us. Mary, though in great pain, sits calmly on my lap. Next to us sits a drug addict waiting for his next supply. His name is G. L. Husse and his terrible predicament means that he is no longer able to keep his job as a post office counter clerk. He had an experience with Methalin whilst on holiday in Spain and since then has not been able to control his craving. He showed me the dropper-jabs in his arm (like bee-stings) and I sympathised. Next to him there was a young man named C. E. Kenne. He kept his hands over his crotch all the time and I wondered why. Looking closer I realized that he had an erection. Later, I found out that he had been in this awkward position since 3 o’clock yesterday afternoon. He is now waiting for some tablets that will permit the blood to leave his organ – this will allow it to descend. While we queued, Mary suddenly told me a most appalling piece of news. Speaking in a hoarse whisper, she confessed that she had been a drug addict for 34 years and that she was now suffering withdrawal symptoms from the killer Letharine. I was speechless and desperate. I grabbed her back thigh and found hundreds and hundreds of needle-marks: blood oozed from many of the punctures and septicaemia was present. I picked her up and hurled her across the room. She dragged herself back to me and, licking at my ankles, begged for kindness, help and understanding. A crowd gathered and a Manager asked me to leave or he would call the police. So I took bruised Mary in my arms and ran out into the street.

***

The doorman at the strip-tease club seemed to know Mary and he lets us in for half-price. It was about 2.30 in the morning and the place was full of men. There was a piano and a low stage. A girl was dancing with no clothes on and she was doing unprintable things with a hedgehog and two slugs. We sat right at the back for fear of being seen. Mr. Jusse, the manager, brought a bottle of fizzy pop to our table and a plate of currant buns. Suddenly Mary jumped off my knee and ran, by way of a ramp, onto the stage. She stood up on her back legs and showed off her parts to the audience of 47. They were furious and booed. Many eggs were thrown and Mary fell to her knees twice. But, undeterred, she continued with her routine. It was revolting, obscene, and indescribable. I blushed and hung my head. The manager ran onto the stage and tried to drag her off. But Mary bit him on the wrist and he ran back to his office with blood streaming down his evening suit. Unable to find a taxi he had to run to St. George’s, where he was given 19 stitches. Appalled by these scenes, the doorman dials 999 and 12 minutes later 37 police constables and 3 detective sergeants made their way down the dark staircase. When the audience saw them, they rose and ran for the EXIT. Many got away but several were caught and dragged upstairs to a waiting police van. When the police saw me, they ran with truncheons and manacles. I was pinioned between two constables and taken upstairs. Mary, completely absorbed by her foul activities, was taken by surprise. She howled bitterly as a constable flung her into a blue hessian sack. The journey to the police station was not without incident. Our driver had been drinking and was unable to keep the van on the road. We collided with several humans who were killed outright and, at the junction of Pell Street, we ran over a toad that was trying to get from Leicestershire to the South Coast. His legs were badly crushed and his neck was severed. I looked back as we sped away and saw him trying to get on his feet again. Just as he was up a City Council gutter cleaning machine came past and swept him into the machinery. After he had gone I found a tiny suitcase near where Toad had been struck down. I opened it, and found 2 pairs of toad’s socks, a change of underwear, a cheap toad’s plastic mac and a pair of slippers. |