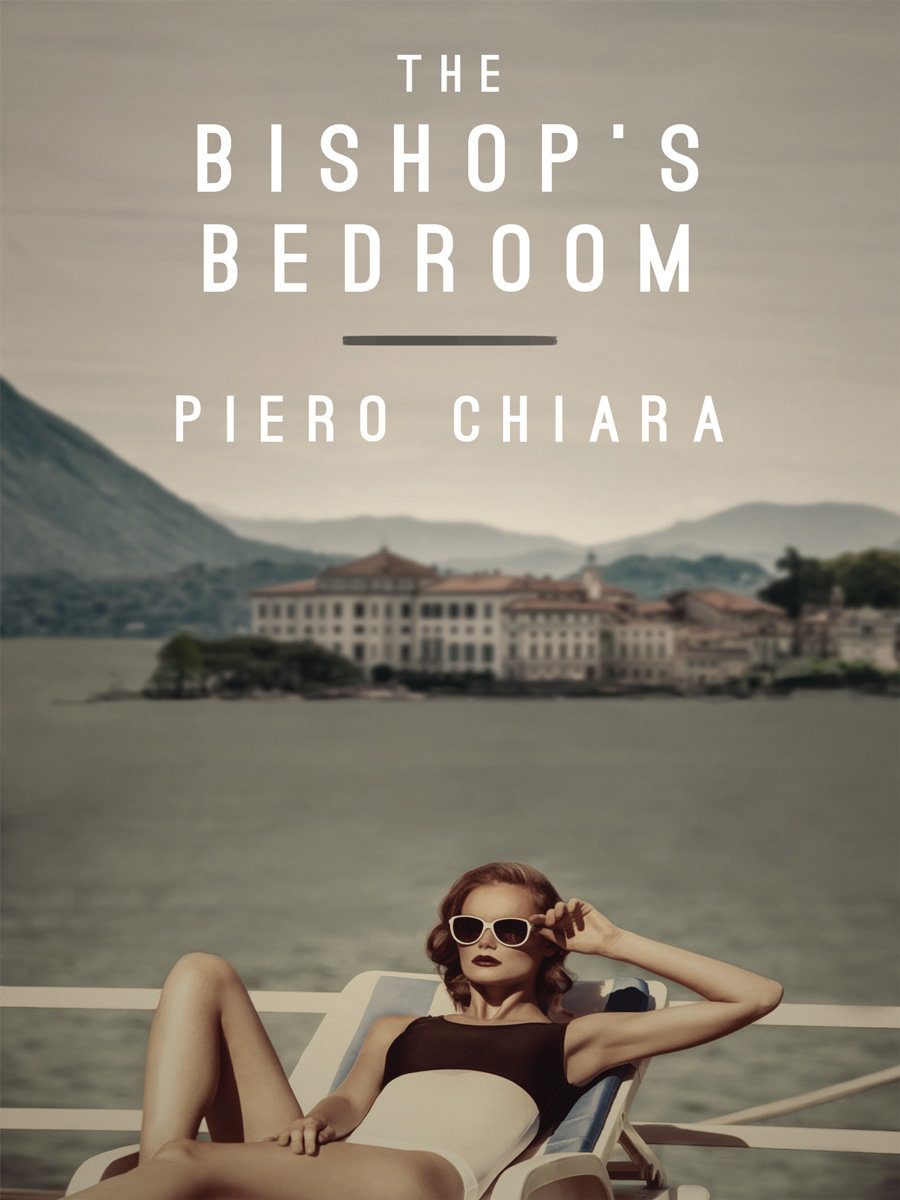

Summer 1946. World War Two has just come to an end and there’s a yearning for renewal. A man in his thirties is sailing on Lake Maggiore in northern Italy, hoping to put off the inevitable return to work. Dropping anchor in a small, fashionable port, he meets the enigmatic owner of a nearby villa who invites him home for dinner with his older wife and beautiful widowed sister-in-law. The sailor is intrigued by the elegant waterside mansion, staffed with servants and imbued with mystery, and stays in a guest room previously occupied by a now deceased bishop related to his host. The two men form an uneasy bond, recognizing in each other a shared taste for idling and erotic adventure. But suddenly tragedy puts an end to their revels and shatters the tranquility of the villa. A sultry, stylish psychological thriller executed with supreme literary finesse.

Excerpt from The Bishop’s Bedroom

In the late afternoon of a summer’s day in 1946, I arrived at the port of Oggebbio on Lake Maggiore at the helm of a large sailboat. The inverna is a wind that rises from the Lombardy Plain every day during good weather and blows the entire length of the lake. Between noon and six o’ clock it hadn’t driven me any farther than that small lakeside village, so I decided to spend the night.

On board alone—as ever, it seemed—I struggled for half an hour to moor the boat in a good position, cover the sails and prepare the berth for the night. All this under the eyes of a middle-aged man who from the moment I’d cast the anchor into the mud of the marina had turned the spectacle of my arrival into his entertainment. At the time, it was fairly common to find vacationers or bored villa owners hanging about in our ports. For them, the arrival of an unknown craft, whether rowboat or dredger, was enough to dispel the melancholy of their stay on a lake. They might have come seeking pleasure and relaxation, but they ended up dealing with all manner of hassle if they were property owners, or being ripped off by hoteliers if they were just tourists. Toward evening, all of them found themselves longing for the seaside, where they could have gone around between the bunkers and recently dismantled blockhouses gorging on naked women, fried fish, dances and films.

Leaning against the iron bar of the railing like a ship’s captain, the man watching me from above the quay didn’t actually fit any of those categories of lakeside malcontents, who realize too late that they’ve made the wrong choice. He had the air of someone with a fondness for the place, and he was enjoying the silence around him. The little houses along the shore, the restaurant, the tobbaconist’s and the sailing shop—always closed—were so devoid of life, movement of people or goods, they looked like they’d been painted on canvas.

Behind the houses a wall of laurel, magnolias, pines, acacias, camphor, and a bit farther up, chestnuts and oaks hung over the water where I was busying myself, turning it green and dark like the bottom of a pond.

Still under the calm and watchful eye of that landlubber standing against the railing, I pulled the waterproof tarpaulin over the boat, covering it for the night. Then I pulled hard on the mooring rope to align the stern with the quayside. I let go of the rope and with one leap, I was on land.

When I got to the top of the granite stairway that led to the pier, I found myself so close to the sole witness to my arrival that it was natural for us to greet each other with a nod and a quiet “Good evening,” the way you do out of courtesy and good manners with people you don’t know in the mountains, at sea or on the water, at any rate, when you’re traveling and you meet other travelers.

I was already headed toward the Ristorante Vittoria when I heard the question: “Excuse me, may I ask you something?”

I turned. “Of course,” I replied.

Without the least sign of flippancy, the man inquired, “What sort of boat do you have? Is it a brig, a barquentine, a sloop or a schooner?”

It wasn’t the first time I’d been asked something like that in these lakeside ports. My boat actually had the solid appearance of a whaler or a bragozzo, and couldn’t be categorized in the recognized tonnage.

“It’s a yacht with a jib and a square-top mainsail,” I replied. “It was designed and built before the war by the engineer Vittorio Quaglino, from Intra. He conceived it for sea-fishing and hoped to build a series. It’s not pretty, but it’s roomy, comfortable and easy to manage—to the extent that I can control it on my own. It has a little kitchen and two couchettes inside.”

Not entirely satisfied, this respectable but curious fellow then asked why my boat was called Tinca; he’d read it on the transom.

“Maybe because it’s squat and potbellied like the tench fish,” I answered. “And it’s the name Quaglino gave it. It’s not to my taste, but I’m used to it. I could have thought of a better one—I’d have liked Tortuga, but changing the name of a boat or ship seems to bring bad luck.”

“You don’t fish?” he asked again. He positioned himself between me and the village.

“No, I don’t. I follow the wind around the lake. At night, I stop in one of these little ports, take a short walk, go and eat in a hotel. Then I come back to the boat and sleep below deck—or if it’s hot, on deck, protected by the canvas.”

“What a life!” he remarked. By now more interested in me than in my boat, he offered me a drink in a cafe in front of us, a local serving sodas and ice cream, and selling punches or perhaps a little grappa during the winter when a few travelers wait there, chilled, for the morning boats to arrive or depart.

He made as if to sit down on one of the straw chairs outside the cafe, and introduced himself: “Orimbelli.”

I, too, said my surname in a hurry. And then I sat beside him in front of the lake, which was now in shadow. We were like two old acquaintances from the village who spend the dinner hour in company with little to say, simply watching the world go by together.

“Your health,” he said, raising his aperitivo.