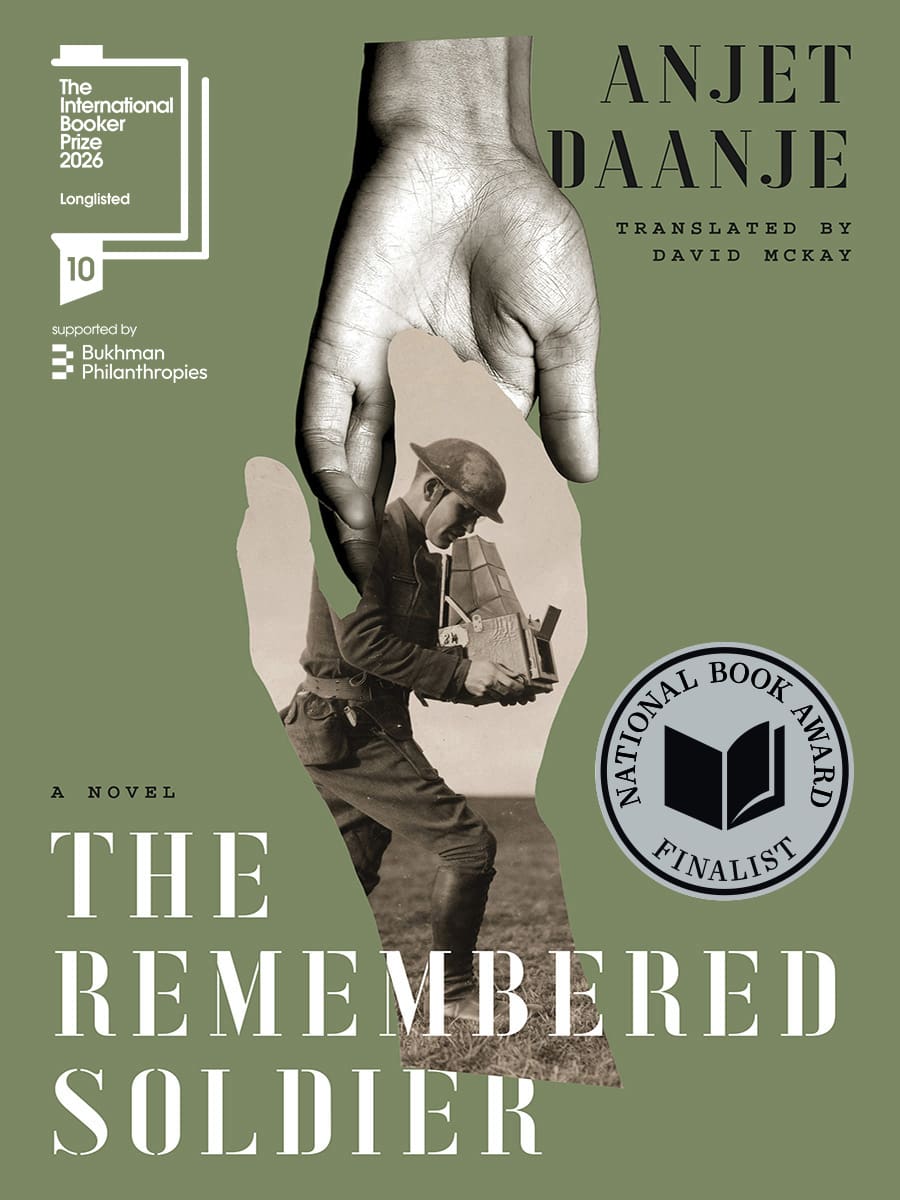

INTERNATIONAL BOOKER PRIZE LONGLIST

NATIONAL BOOK AWARD FINALIST—THE NEW YORK TIMES 100 NOTABLE BOOKS OF 2025—THE WALL STREET JOURNAL 10 BEST BOOKS OF 2025—PUBLISHERS WEEKLY 2025 BEST BOOKS OF THE YEAR—CHICAGO PUBLIC LIBRARY BEST BOOKS OF 2025 —THE NEW YORK TIMES “The Best Historical Fiction”—2026 PEN TRANSLATION PRIZE FINALIST—REPUBLIC OF CONSCIOUSNESS PRIZE FINALIST

An extraordinary love story and a captivating novel about the power of memory and imagination. Flanders 1922. After serving as a soldier in the Great War, Noon Merckem has lost his memory and lives in a psychiatric asylum. Countless women, responding to a newspaper ad, visit him there in the hope of finding their spouse who vanished in battle. One day a woman, Julienne, appears and recognizes Noon as her husband, the photographer Amand Coppens, and takes him home against medical advice. But their miraculous reunion doesn’t turn out the way that Julienne wants her envious friends to believe. Only gradually do the two grow close, and Amand’s biography is pieced together on the basis of Julienne’s stories about him. But how can he be certain that she’s telling the truth? In The Remembered Soldier, Anjet Daanje immerses us in the psyche of a war-traumatized man who has lost his identity. When Amand comes to doubt Julienne’s word, the reader is caught up in a riveting spiral of confusion that only the greatest of literature can achieve.

Excerpt from The Remembered Soldier

And they slip up the stairs to their bedroom without a sound, she checks in on the children and then flumps into bed and kicks off her shoes as she pulls up her dress and unfastens her garters, and he sits down next to her and does what his feelings of guilt made him decide to do hours ago, he tells her his most dreadful nightmare, the young dying soldier, the boy’s innocence, his own pain, his anger and jealousy, and how he delivers the lad from his misery for just the wrong reasons and what that says about him, the man she married. And she gives him her full attention, she asks no questions, all she does is hold his hand, and when he reaches the end of the story, she takes him in her arms and strokes his hair and back as a mother strokes her child, and she presses his face to her shoulder as if to make it clear she wouldn’t blame him if he burst out sobbing, and still she says nothing and he feels understood, what she grants him is a wonder of wordless human understanding, forgiveness for all the things he can’t forgive himself for. She knows just what to do, that’s his foolish feeling, as if she’s done it before, not once or twice, but dozens of times, until she mastered the skill to perfection, and although he distrusts her compassion, it remains tempting, the idea that he’s no longer alone, tears sting his eyes, a thick lump fills his throat, he swallows and swallows again and tries not to cry, and she waits in polite silence for him to recover, and she can even do that without slighting his masculinity, and then she carefully lets go of him and kisses him. And she goes on undressing, still saying nothing, and he takes off his own clothes in silence, and they make love as if neither of them knows what else to do, her thoughts are elsewhere, and he thinks that behind all her understanding she must be hiding her disgust with him, and he goes to great lengths to pleasure her, kissing her breasts and caressing her between her legs and putting off his own release like a gentleman.

And then out of nowhere she says, as if they’re already in the middle of a conversation, that she wants to tell him something, here it comes, he thinks, his heart pounding, and he feels like snatching up his clothes and fleeing the house, but he rolls off her and lies beside her. And she says that on the day of his mobilization he wanted to flee to the Netherlands with her and Gus, and she talked him out of it, they would have had to leave everything behind, the successful photography business they’d put so much hard work into building up, their family and friends, their whole life, and they would never be able to return, because desertion was punishable by death, she says, and she lets a silence fall, expecting a response from him, but he says nothing. And she adds, in her defense, that she didn’t know there’d be a war, a real war, she means, and she wasn’t the only one, she says, everybody thought it was a lot of fuss about nothing, Belgium was neutral, why would the Germans be so foolish as not to respect that, and if Belgium got tangled up in a war, the Germans would probably be defeated by Christmas, that’s what everyone thought, she repeats, everyone but him, but he always saw objections and difficulties, and it was her job to wave them aside, that’s how it had always been since the first day they were together, so she waved aside the war for him too. We separated as if we’d see each other again in a month, she says, and her voice wobbles and maybe her eyes fill with tears, he can’t tell in the dark, and he understands that for the past eight years she’s regretted her naive flippancy and pictured that new life in the Netherlands with him and the children, but her sense of culpability is an illusion she’s spun for herself, as if she needed something, anything, to feel guilty about.

And she whispers his name, punkin, she calls him, and it sounds like a plea, and he gives her what she longs for, he grants absolution, just as she absolved him for the death of the young soldier from his dreams, but something’s wrong, he couldn’t say just what, it’s the tone of her confession, the time she picked out for it, the weight she lends to it, and in any case, the forgiveness he grants her doesn’t seem to help. A blanket of fear descends on him, he knew it as he stood in front of their undamaged house in Meenen, there’s too much she’s not telling him, and he doesn’t dare ask why, he’s not sure she knows the reason herself, maybe the truth is so shocking she refuses to face it. And he says he’s tired and ready to sleep, oh, yes, of course, she says, taken by surprise, and after a moment she says sleep well and then falls asleep, or makes a very convincing pretense, he suspects that’s more likely.

And his thoughts will not settle, they dance around in the same suffocating circle, he said goodbye to her and Gus at the platform, he remembers that, and he was looking forward to the war, going to the front was an adventure for him, and he even felt guilty toward her for feeling that way, and now she tells him he was so scared that he wanted to flee to the Netherlands with her. It’s not that there are too many questions, it just seems that way because he can’t see the big picture, all these questions probably have just one answer, and he has the feeling the answer’s so simple he actually already knows it, like a word on the tip of your tongue that just won’t come to mind. He lies beside her and his fear colonizes the darkness around him, hiding under the bed, scaling the pitched roof, rustling among the garments on the line, shivering under the blankets, and he reaches for her hand and whispers, are you sleeping, and she answers at once, her voice is as clear and resolute as if she’s swept away all petty cares, she puts her arm around him and lays her head on his chest and tells him about the day he taught her to ride a bicycle, about the taste of wild strawberries and how they laughed at the farmer who thought she was a man, and he thinks she knows it too, their life is built on quicksand, one false step and they’ll drown together.