THE WORDS THAT REMAIN Wins the National Book Award

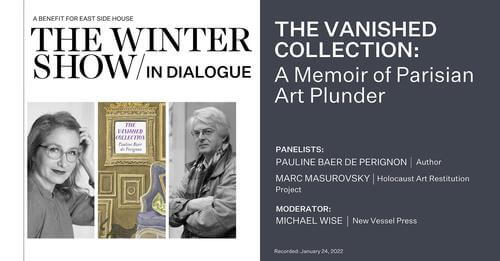

Watch a video discussion of Nazi art plunder in Paris with THE VANISHED COLLECTION author Pauline Baer de Perignon and Holocaust Art Restitution Project co-founder Marc Masurovsky in a program co-sponsored by The Winter Show and American Friends of the Louvre. Click here to view.

THE EYE unveils secrets of Old Masters connoisseurs.

Learn about a rare and secret profession by watching this video of an online conversation, sponsored by American Friends of the Louvre and the National Arts Club in New York, with art historian Philippe Costamagna about his book THE EYE: An Insider’s Memoir of Masterpieces, Money, and the Magnetism of Art. Click here to watch this event for free.

Translator Ann Goldstein introduces Distant Fathers

Watch an insightful discussion of Distant Fathers with translator Ann Goldstein and Italian novelist Marta Barone, sponsored by Rizzoli Bookstore. Click here for video.

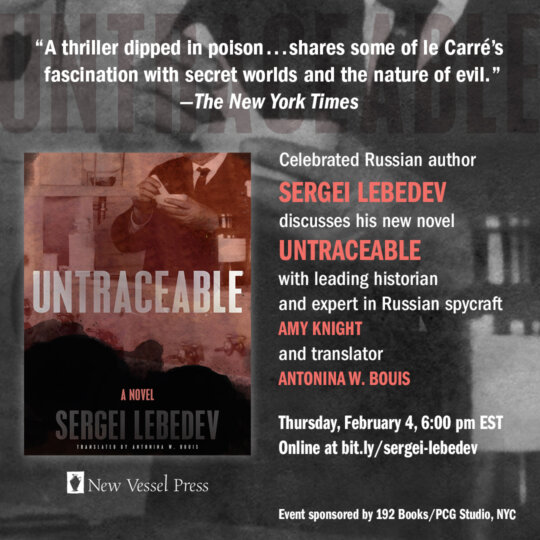

Sergei Lebedev discusses his new novel UNTRACEABLE.

Watch a video of celebrated author Sergei Lebedev in a discussion of his timely novel UNTRACEABLE with leading Russian spycraft expert Amy Knight and translator Antonina W. Bouis, sponsored by 192 Books in NYC. Online at bit.ly/sergei-lebedev

The New York Times profiles UNTRACEABLE author Sergei Lebedev

The New York Times profiles novelist Sergei Lebedev in an article calling his new book UNTRACEABLE “a thriller dipped in poison” with a John le Carré-like “fascination with secret worlds and the nature of evil.”

Villa of Delirium featured in The New York Times

Villa of Delirium is featured in a special report in The New York Times about the fanciful house on the French Riviera that inspired the novel by Adrien Goetz.

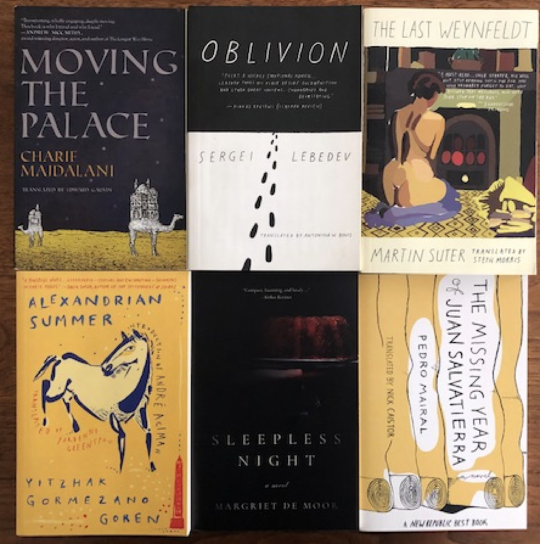

Stay Open to the World Package

Stay open to the world: Read literature in translation with this fantastic discounted package of six books that will take you to Sudan, Lebanon, Russia, Argentina, Switzerland, Egypt and the Netherlands. An extraordinary literary journey for just $60, and we’ll provide free shipping (U.S. residents ONLY). This package comprises one copy each of Moving the Palace, Oblivion, The Last Weynfeldt, The Missing Year of Juan Salvatierra, Sleepless Night and Alexandrian Summer.

https://store.newvesselpress.com/stay-open-to-the-world-package-of-six-books/

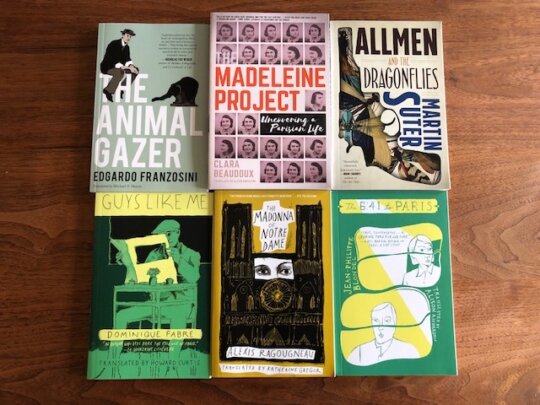

European Travel Package

Enough quarantine, let’s go to Europe! These six books will take you to Paris, Zurich, Milan and Antwerp. An extraordinary literary journey that’s yours for only $60, with free shipping included (U.S. residents ONLY). This package comprises one copy each of The Madeleine Project, Allmen and the Dragonflies, Guys Like Me, The Animal Gazer, The 6:41 to Paris and The Madonna of Notre Dame.

Click here to purchase:  https://store.newvesselpress.com/european-travel-package/

https://store.newvesselpress.com/european-travel-package/

The Drive – Video Discussion with Author Yair Assulin

THE DRIVE by Yair Assulin is a powerfully subversive novel in a long tradition of anti-militarist literature, with existentialist echoes of Céline's Journey to the End of the Night, Remarque's All Quiet on the Western Front and Hašek's Good Soldier Švejk. Watch the video where novelist Ruby Namdar lays it out in an engrossing discussion with Assulin and his Booker Prize winning translator Jessica Cohen.

Posted by New Vessel Press on Monday, April 20, 2020

Catalogue 2019-20

Author of THE MADONNA OF NOTRE DAME on the Cathedral’s Future

Notre Dame’s Charred Glory and the Challenge of Globalized Modernity

Ten years ago, I worked in the Cathedral of Notre Dame in a job that consisted of ensuring the two groups that came to the massive church every day—the worshipers and the tourists in the tens of thousands—got along with each other. Notre Dame de Paris is as much a Tower of Babel as a Christian bastion, performing a dual role as a church and a monument accessible to the world.

One summer afternoon, I took a break from my task as a crowd monitor in the sanctuary and managed to ascend to the upper framework of the building. It was one of the most extraordinary sights I’ve ever seen—a tangle of beams that has been dubbed “the forest” because it required cutting down a thousand oaks to build it. The ascent into the heart of this structure was like finding oneself in the hold of an immense galleon. To be there was also to come into dialogue with those whose hands created it in the 13th century, working with the knowledge that they themselves would never see the result of this phenomenally long-range construction project. To ascend into the forest was to feel roots under your feet.

A small door gave onto the roof. The lead tiles gave off a blinding light and radiated intense heat. The panorama over the Ile de la Cité took my breath away. At a height of two hundred feet, one was no longer in a ship’s hold, but rather among its masts. Notre Dame de Paris is a vessel that navigates along the River Seine between a glorious past and the challenge of a globalized modernity.

Using these experiences, I’ve written two novels set in the cathedral. The main protagonist, Father Kern, develops the idea that guides his actions: the primary divide among people doesn’t derive from religion, skin color or social standing; the true divide is between doves and hawks; the willingness to extend one’s hand rather than give into the temptation to withdraw into oneself.

On April 15, the forest burned. The roof melted and the great spire that dominated the cathedral collapsed, piercing the edifice’s very heart. The upper level, where it was possible to see things in perspective, is no more. That night, the people of Paris gathered to watch their cathedral ablaze. Believers and non-believers, each suddenly feeling less anchored in the earth. In the ensuing hours, an amazing mobilization occurred. The French government called for a restoration within five years. An architectural competition was announced. And nearly a billion euros were collected from businesses and private individuals to reconstruct the ravaged Notre Dame.

Then the first controversies broke out—very French battles: Should the reconstruction be identical to the old? And all this money donated by billionaires, why couldn’t they have given it instead to those who live on the streets? Notre Dame de Paris is, in both its sublime history and its tragic fire, the symbol of nation consumed in its opposition to the past and the future, the right and the left, rich and poor. A country no longer in harmony nor even capable of self-understanding.

At times the same thing can happen with monuments as with individuals: it’s in the moment that we fear losing them that one realizes how much we value them. Confronted by the cathedral’s fragility, even though its wall are still standing, we remember the imperative to watch over our heritage, material and spiritual. France is a living democracy in a Europe that has ensured us decades of peace and, no matter what one says today, a certain degree of prosperity. Perhaps we have come to take it for granted, to consider it a given, just as we have at times passed by Notre-Dame without even seeing it.

Forgive me for seeking to find meaning in this conflagration, but it’s the inveterate habit of a writer to see metaphors everywhere. To see the big picture, as you say in English, and God knows that our British friends are taking the measure of the violent fire now ravaging their own country. Certain ideas and values have united us as a people. They don’t have the solidity of stone but they have passed the test of time. The artisans who built them piece by piece made sure everyone could take refuge in them and feel reassured. Certainly, it’s necessary to undertake renovation, keep European democracy up to date, avoid its mummification, and prevent it from being distorted by a few with great power.

That terrible night, around 9 p.m., the fire began to move toward the north tower. The heroic firefighters managed to contain it. If the north tower had collapsed, the entire cathedral would have fallen, and all would have been lost.

So in the face of the ravaged monument that thankfully endures, let’s take care not to feed the fire by giving free rein to pyromaniacs who benefit from populism and set citizens against one another by stoking the rage that currently prevails within the country. And because the Notre Dame fire and its aftermath have touched people everywhere, it’s clear that this need for vigilance also applies around the world.

Alexis Ragougneau is the author of The Madonna of Notre Dame

Catalogue 2018-19

Banned Books Week 2017

It’s Banned Books Week, and we’ve put together a little reading guide featuring books from New Vessel Pressand a few other great indie presses who publish literature from around the world, including Open Letter, Archipelago Books, Deep Vellum, Grove Atlantic, and Bellevue Literary Press. We’ve included works by authors whose work has been repressed by both hard and soft means: sometimes, a book doesn’t have to be put on an official “Do not publish” list to disappear from discourse. Quite often books, or authors, are simply ignored, newspapers are pressured not to review certain works, or authors are forced to flee their homelands or face severe repercussions, though all “unofficially.” This expansive understanding of “Banned Books Week” allows us to widen our perspective and think about what it means to muffle voices of dissent inside a country, or culture. We hope you’ll choose a few of these books and give them a read. They’re not only insights into foreign cultures and disturbing histories, they’re also, quite simply, very enjoyable literature.

You can download the guide here and share it with friends. Thank you!

Catalogue 2017-18

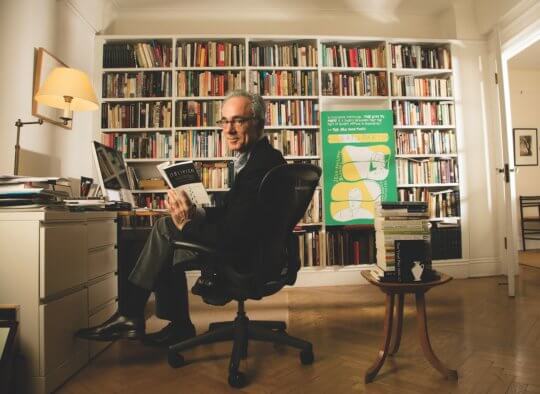

Crain’s New York Business on New Vessel Press becoming “an instant classic.”

Found in Translation:

How a publishing company ‘spun gold out of nothing.’

By Peter S. Green

It began as idle chatter. Two multilingual literature buffs met at a middle school spelling bee and talked about the foreign books they’d read that had never been published in the U.S. Why not, they thought, open a publishing house and translate their favorites?

“But neither of us had any experience in book publishing,” said Michael Wise, a former Central Europe correspondent for Reuters.

New Vessel Press, founded in 2012 by Wise and Ross Ufberg, then a Ph.D. candidate in Slavic studies at Columbia University and now an editor at online magazine BreakGround, translates and publishes six books annually. The pair pooled $100,000 of their own money to start it. The money went quickly to buying publishing rights, hiring translators and a cover designer (up-and-coming New Yorker cartoonist Liana Finck), building a website, publicizing their venture and paying for printing their first year’s catalog, all before a single book was sold.

Finding manuscripts isn’t hard. Only 3% of books published in the U.S. are translations. The men travel to book fairs in Germany and the United Arab Emirates, get recommendations from friends and read voraciously—Wise is fluent in German and French, and Ufberg, in Polish and Russian. They have become a go-to outlet for foreign publishers. “We look for novels and nonfiction that put you in another place, give you access to another culture, transport you,” Ufberg said.

“What we are doing is all the more important because of the politicians who would just as soon ignore the rest of the world,” said Wise.

Their first book, The Missing Year of Juan Salvatierra by prominent Argentine writer Pedro Mairal, was named one of New Republic’s 10 best books of 2013. Oblivion, a dive into the legacy of Soviet-era prisons by Sergei Lebedev, was chosen by The Wall Street Journal as one of the top 10 novels of last year. “Every other book on that list was by a major corporate publishing house,” Wise said.

Their latest is The Madeleine Project by French journalist Clara Beaudoux, who discovered a storeroom full of papers and photographs belonging to the previous tenant of her Paris apartment and reconstructed the woman’s life through a multiyear storm of tweets. “It’s a graphic novel of the digital age,” said Wise.

“Ross and Michael have really spun gold out of nothing; they’ve really made an instant classic out of New Vessel,” said John Oakes, director of the New School Publishing Institute and co-founder of OR Books.

Critical success aside, making money in the book business is tough. New Vessel lists books for $16, which are sold wholesale for $8, minus a $2 or $3 fee to the distributor. Translations can cost from $3,000 to $10,000, depending on the length and difficulty of the text and the renown of the translator. Grants from foreign cultural institutions cover about a third of the cost of translation.

The partners say they are approaching profitability, with revenue in the low six figures. Their titles sell between 3,000 and 7,000 copies, and sales were up 40% from 2015 to 2016. New Vessel buys worldwide English-language rights, making some money by selling to publishers in Great Britain and Canada. Occasionally, New Vessel gets a cut when a title is optioned for film, like Killing the Second Dog, by late Polish writer Marek Hlasko. Actor Richard Gere helped convince Hollywood studio Tadmor Films to option the screen rights for the tale of two down-and-out Poles scamming lovelorn women in 1960s Tel Aviv, Israel. New Vessel stands to earn a six-figure fee.

Another strategy is to find the next Stieg Larsson, the late Swedish author of the best-selling Millennium trilogy. The pair sees potential in Martin Suter, a German-Swiss crime writer who sells hundreds of thousands of books in Europe. His art-fraud thriller The Last Weynfeldt, published last year by New Vessel, is the first of a three-book deal that Ufberg hopes will gradually seed the market. “Suter didn’t become the biggest-selling author in Germany overnight,” he said.

Marketing remains a challenge. New Vessel offers an annual subscription for $72. Volume is still low, so Ufberg wraps all the subscription books in pastel crepe paper himself, the kind of personal touch that distinguishes New Vessel from large-scale publishers. They organize tours of major U.S. cities for their authors (paid for by the universities and cultural centers they visit). Reviews in The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal give them material to share during a book’s social-media campaign. Ufberg and Wise also occasionally set up a folding table in front of Zabar’s on the Upper West Side, where selling 30 books on a slow afternoon is a success. That’s given them a freedom absent at larger publishing houses that are guided by marketing studies. “We don’t have to pass things through a committee,” Ufberg said. “If we say it’s a fantastic book, we can just publish it.”

And they are reassured that enough people want what they can provide. “Our sales are up,” said Ufberg. “A lot of people are looking for entertaining, intellectual, good reads, and as long as we can keep providing them, we’re OK.”

A version of this article appears in the May 1, 2017, print issue of Crain’s New York Business as “Found in translation”.

Library of Congress lecture by Salvatore Settis on IF VENICE DIES

Can be viewed here:

Salvatore Settis Schedule of U.S. Appearances

Salvatore Settis, author of the much acclaimed book If Venice Dies, will be embarking on a U.S. tour, with stops in Providence, Washington, D.C., New York, Philadelphia, and Los Angeles.

Tuesday, October 25, 7 p.m.

Brown University lecture; Providence, R.I.

http://www.brown.edu/Departments/Joukowsky_Institute/events/

Thursday, October 27, 3-4 p.m.

Library of Congress; Washington, D.C.

https://www.loc.gov/rr/european/calendar/calendar.html

Sunday, October 30, 2 p.m.

Philadelphia Museum of Art

The Irma and Herbert Barness Lecture

http://www.philamuseum.org/calendar/?gv=0&id=30&et=7&dt=October_2016

Monday, October 31, 4 p.m.

Conversation with author and journalist Alexander Stille at NYU Casa Italiana, New York City

http://www.casaitaliananyu.org/content/book-presentation-if-venice-dies-with-salvatore-settis-and-alexander-stille

Tuesday, November 1, 12 p.m.

92nd Street Y, New York City

http://www.92y.org/Event/If-Venice-Dies

Wednesday, Nov. 2, 6-7:30 p.m.

Bard Graduate Center, New York City

The Protection of Cultural Heritage in Italy: A Short History and Some Current Issues

http://www.bgc.bard.edu/news/events.html

Saturday, Nov. 5 – 2 p.m.

Museum Lecture Hall, The Getty Center, Los Angeles

http://www.getty.edu/research/exhibitions_events/events/settis_venice.html

Catalogue 2016-17

Interview with Klaus Wivel

You speak about it a bit in the book, but could you tell us the impetus for The Last Supper?

For many years I’d been covering the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. After the collapse of the peace negotiations in 2000 the Second Intifada began. I reported from the Palestinian side and it became clear from talking to Christian Palestinians that a shift had taken place in the struggle for Palestinian nationhood.

Palestinian Christians had always been a crucial part of the nationalist movement. The Palestinian cause was about culture, history, and language before religion, which meant the both Christians and Muslims could partake in this endeavor.

However, from 2000 the definition of being Palestinian shifted and Islam became more and more the main denominator. This meant the Palestinian Christians began to feel like strangers in their own land. On top of that the methods in combatting the Israelis also shifted to include suicide bombings, which Palestinian Christians did not want to be a part of. Hence, they where looked upon by many militant, Islamic Palestinians as traitors to the cause. Thousands of Palestinian Christians began to emigrate. They felt trapped between the Israeli military on the one side and the militant Palestinian Islamic fundamentalists on the other. Christians in Bethlehem told me that if the level of emigration continued at this pace, Bethlehem would be emptied of Christians within a few decades. I knew this had to be an enormous story in the West, that the birth place of Christ was being abandoned by Christians. However, the story never really got much attention. This puzzled me.

I also learned about Christians leaving other Arab countries. In 2006, for instance, it was mentioned that two thirds of the Christians in Iraq had fled the country following the Iraq War. Churches were being bombed, Christians kidnapped, priests killed and whole Christian neighborhoods in the two biggest cities, Mosul and Baghdad, ethnically cleansed. This too failed to create a big media story in the West, despite the fact that the Christian community in Iraq is one of the oldest in the world.

When Copts in Egypt became the target of persecution after the fall of President Hosni Mubarak and began to leave by the thousands, I wrote an open letter in my newspaper, the Danish weekly Weekendavisen, calling upon the new Danish foreign minister to arrange a meeting with ambassadors from the Muslim countries and ask them how they were going to protect the Christian minorities in their countries. He never answered. I decided that it was time to pay the Christians a visit in the Arab countries and ask why so many were leaving.

The entryway to the small church of St. Simon the Tanner in Cairo’s garbage city, home to a large community of Coptic Christian garbage collectors and recyclers.

What was the most difficult part about covering this story? Were you ever in danger?

I’m certainly not a reporter who would head for danger if I could avoid it, but there were a couple of dramatic situations. In Cairo for instance I went to Tahrir Square, the epicenter of the Arab Spring demonstrations in Egypt, with a Christian, female journalist. In one of the backstreets we were accosted by thirty or forty teenage boys who looked as if they hadn’t slept for days and were on the verge of running amok.

Tahrir Square has become notorious for the mistreatment, harassment and raping of women–three women had been stripped nude by a major crowd the day before our encounter–which is why women at that time more or less stayed away from the square unless they were completely covered up. The boys that encircled us began to harass the woman who, being a Christian, refused to wear a headscarf. We were completely outmatched, but she managed to talk her way out of the crisis and we were able to get away shaken, but unharmed. After that she said: “Don’t ask me why Christians want to leave Egypt. Ask me why they want to stay.”

There are many moving and troubling passages in this book. But one of the strangest stories, by far, is that of Andrew White, the pastor of St. George’s Anglican Church in Baghdad. We get to meet him, of course, but tell us a little more about your experience with him, what he is like as a person.

I had heard of him in Christian circles in Denmark where he was spoken of as an almost mythic figure, because he is among the only Westerners with the guts to stay in Baghdad outside of the Green Zone during the Iraq War despite having a prize on his head from Islamist groups. Churches had been bombed in the city, Christians had been kidnapped and most of the Christians had left. But he stayed on to help both Christians and Muslims get through the horrible war with a school and medical clinic.

When I went to Baghdad to meet him he me picked at the airport with a heavily armed military escort that drove me through town at 90 miles per hour to his church in the middle of Baghdad, probably the most fortified church in the world. The vicar is huge in every way—big feet, big body, big head, big ideas—but since he suffers from sclerosis, he walks with a cane and often has to be seated. As a friend of Denmark, he had erected a monument in the middle of the courtyard with the names of the nine Danish soldiers who had died during the Iraq War. The vicar had been in favor of the war (but not how it was being fought), he cherished living dangerously while helping the poor, there were books on Jewish mysticism on his night table, and he spoke with warmth about Israel. Not many with that mindset in that city at the time, I’m sure.

You visited four “lands” – Egypt, Lebanon, the Palestinian Territories, and Iraq. It seems as though in all of them Christians face a bleak future. However, did you see any chance for survival there, any reason to hope?

It differs from country to country. The Iraqi situation is the bleakest. I visited areas around Mosul to the northeast that were conquered by ISIS in the summer of 2014 and where all the Christians, over 100,000 of them, have had to flee. In Iraq they face ethnic cleansing. Outside the Kurdish areas there are only few Christians left. They are not likely to return any time soon, if ever.

In the West Bank, however, the situation for the Christians today is better than in many years. In 2007 the Palestinian Authority and the Israeli Army drove Hamas underground and since then some Christians have returned. In Egypt, Christians are also doing better since the Muslim Brotherhood was evicted from power in the summer of 2013. However, it’s important to note that in every Arab country except Lebanon, Christians do not have equal rights. Just to give one example: A Muslim man can marry a Christian woman, and then their children will become Muslim. But a Christian man cannot marry Muslim woman. Discrimination like that—and there are many more examples—relegates the Christians to second-class citizens. In times of crisis the Christians are the group that is being scapegoated.

How long did it take you to write this book? When did you do the research?

A little less than a year, from the autumn of 2012 to the summer of 2013. I took one country at a time and wrote the chapter on each before travelling to a new country, except for the chapter on the Palestinian Christians, for which I returned to visit the Christians in Gaza.

Were you afraid that people would see your reporting as being mission-driven: in other words, that when you were writing, you already had an objective and an ulterior motive in mind? What do you say to critics who might ask, Why not write about every religious group that’s being persecuted?

I knew I would be accused of having an ulterior agenda. In Denmark and in Europe (and in the US, I guess) the debate on Islam and Muslims has been contentious for years and I knew I would be venturing into a minefield. Some told me before I began that I only was writing this book because I was Christian. This is why I make a point of saying that I’m not Christian. I was never baptized. I consider myself an atheist.

Others were certain that I wrote the book to put Muslims in a bad light. I guess the consequence of this line of thinking is that you shouldn’t write stories where Muslims appear as the perpetrators, not even when they clearly are. How this can be seen as a morally right thing to do escapes me.

Some would also criticize me for only focusing on the Christians when other minorities in the Middle East also are suffering. But despite my secularity I fail to see why being interested in the fate of the Christians in the Middle East, the origin of the dominant religion of the West, can be seen as dubious. Frankly, I have for years found it odd that it’s not more discussed than it is.

In a word: Anyone who reads the book will hopefully understand that this is a piece of journalistic work. I aim to convey that the situation for Christians in the countries I visit is so dire that we must shed light on it.

There was great controversy in Denmark after the book was published there in 2013. What were the different responses to your book? And how did you react? Were you surprised?

The book certainly received a lot of attention when it came out, mostly because most Danes were simply unaware of what was going on when it came to the Christians in the Middle East. But the book mostly got fine reviews on all sides of the political spectrum. I hope it shone through that I managed to be balanced and fair. But I’m critical in the book towards influential academics in the field of Middle East studies who in my view have completely neglected this topic and who have appeared apologetic towards the Islamic world. Naturally they were not too fond of this. However, after the ISIS attacks on Christians in Iraq and Syria, the gravity of the situation became evident to everybody. Last fall the new center-right Danish government included in its platform that it would show special attention to the persecution of Christians and other minorities around the world. I’m sure my book has played a role in this.

How would you respond to politicians and other persons of influence who might be reluctant to speak out about the persecution of Christians for fear of inflaming tensions between U.S./Europe and the Muslim world?

We cannot afford to abandon minorities facing extinction, and we are not doing the Muslim countries any favors by evading a forceful response. Christians in the Middle East have been great merchants, businessmen and artists for centuries, and many Muslims are well aware how much more impoverished and monolithic the area would become if the Christians left. We cannot close our eyes to the fact that for years Islamists have persecuted Christians all over the Middle East. As I write this, at the end of March 2016, an attack on Christians in Pakistan has just killed over 70 people. The question to those who fear “inflaming tensions” is: How has our silence helped this minority?

You wrote the book after the murder of Daniel Pearl but before the killings of several Westerners by ISIS. Are you planning to return to the region yourself to do further reporting of this kind? How do you see the outlook for similar reportage on human rights conditions in the societies you visited?

I would be thrilled to go back, but I was sent to New York to cover the US after the book came out, so the Middle East is not the topic I’ve been covering these past few years. That’s why I haven’t returned since I wrote the book.

For years there was too much focus on Israeli atrocities and way too little attention given to abuses in other Middle Eastern states. I don’t say this because I wish to shield Israel from bad press. On the contrary: I have a view that shouldn’t be very controversial—especially coming from a journalist—but in strange way it is. A critical press is good for any country. We take this for granted in the West. Although Israel dislikes the negative attention it receives from Western media (including its own) and generally doesn’t see it like this, media scrutiny is basically a service to the country; the same argument can be made for all countries. And on the flipside: the lack of scrutiny given to Arab regimes especially in the European press has been a betrayal of the Arab peoples living there. It treats them as if they were too fragile and immature to deal with the inquiry we expect the press to accord our own Western societies. Human rights groups have had the same fundamentally flawed approach to the Middle East.

Since the Arab Spring this has changed. At the moment I think we have many excellent and courageous journalists living in the Middle East doing important human rights stories.

Say something about the people who helped you on the ground.

Since Arab countries are more or less closed societies it’s crucial to have locals helping you. I’ve had help in all the countries, but in places like the Palestinian Territories and Egypt, some assisting me didn’t want me to publish their names for fear of retribution. Journalists often forget to state the obvious: that there is very little freedom of speech in some of these places. You can’t expect people to give you a truthful answer.

In Egypt and the Palestinian Territories dissidents are in fear of ending up in jail. This is one reason why it’s easier to work as a writer than as a TV journalist. People will—and this was specially the case in the Palestinian Territories—often say one thing when a camera is on, and another when it’s off. It was highly evident among the few thousands Christian who were still living in Gaza under Hamas rule. Christians—especially here, but in many other places—are in a way doubly oppressed. Not only by a government that allows little dissent from Muslims and Christians alike, but also from a dominant Muslim society where Christians are treated with contempt amid increasing radicalization. In such places you have to rely on anonymous sources.

What other stories have you covered? What have you been covering since you left the Middle East? You worked for a year as the New York correspondent for Weekendavisen. What was your favorite story here? The most interesting/strangest/most memorable place you visited?

I’ve been working as a journalist since 1998 so I’ve covered many stories and also allowed myself to do many different genres of writing, like interviews, reviews, essays, etc. I’ve also been editing for my paper over long stretches of time. A few months after writing the book on Christians in the Middle East, I helped to write the autobiography of one of Denmark’s most notorious and famous bike riders, Michael Rasmussen, the Danish version of Lance Armstrong. Of course, like everybody else he had been doping too, and he spilled the beans to me. Great story that caused a sensation in Denmark and abroad, but, well, quite different book from the one I’ve been talking about here.

I actually spent two years writing from New York: I came back to Copenhagen last summer. I’ve covered everything in the U.S. from the potter’s field at New York’s ghostly Hart Island where prisoners bury the unclaimed dead, to the water shortage in California, bull fighting in Texas, artists in Detroit, prison education inside Taconic Correctional Facility in Bedford Hills, following the campaign trail in Colorado, and many interviews and book reviews. I also took the time to go to Chile to write about how former dictator Augusto Pinochet plagiarized his history professor in one of his books while serving as president, and to do a story about a soccer team in Chile, one of the country’s best, started by Palestinian, Christian immigrants. Of course, I wanted to know where they went and what they did when they left the Middle East. They played soccer, I guess.

I certainly wouldn’t mind spending many more years in the Americas.

Upcoming events with Klaus Wivel

Klaus Wivel, author of The Last Supper: The Persecution of Christians in the Middle East, will be participating in the following events:

Wednesday, April 27

6:00 – 7:30pm

Carnegie Council on Ethics and International Affairs

In conversation with James Kirchick

170 E. 64th St.

New York, NY 10065

https://www.carnegiecouncil.org/calendar/data/0617.html

Thursday, April 28

6:30 – 10 p.m.

PEN World Voices Festival

Westbeth Center for the Arts

55 Bethune Street

New York, NY 10014

http://worldvoices.pen.org/event/2016/01/24/literary-quest-westbeth-edition

Friday, April 29

12:30-1:30 p.m.

Lunchtime discussion

LL 309 | Lowenstein Center

Lincoln Center Campus | Fordham University

New York, NY 10023

http://www.alumni.fordham.edu/calendar/detail.aspx?ID=4425

Saturday, April 30

2:30-4:00 pm

PEN World Voices Festival

Zoom In/Zoom Out: Europe

With Karim Miské, Klaus Wivel

Moderated by: Adam Shatz

Dixon Place

161A Chrystie Street

New York, NY 10003

http://worldvoices.pen.org/event/2016/02/09/zoom-inzoom-out-europe

Tuesday, May 3

6:30-8:00 pm

Book talk, followed by Q&A

Scandinavia House

58 Park Ave

New York, NY 10016

http://www.scandinaviahouse.org/events/the-last-supper/

Thursday, May 5

7:30-9:00 pm

Foreign Policy Initiative

Salon evening

Exact time and address TBA

Washington, DC

Interview with Alexander Pschera, author of Animal Internet

How did you first hear about the idea of the Animal Internet, and what was it that got you interested enough to write a book about it?

How did you first hear about the idea of the Animal Internet, and what was it that got you interested enough to write a book about it?

The whole thing started when I encountered Waldrapp Shorty on Facebook. This bird is part of a zoological project, but on Facebook it looked like a joke. First I thought it was fake—an ugly bird with its own Facebook account? Can’t be … Then I realized step by step that this was no joke, but a very, very serious development. Serious for the bird, serious for the people trying to reintroduce nearly extinct Waldrapps into the European wilderness—which is, by the way, a tough job—and even more serious for the social media followers who spent days and days with Shorty, taking and posting photos, commenting on his behavior and so on. I understood that there was a big story behind this individual bird tagged with a sensor—a story which had the power to change the notion of “nature” and to transform the human approach to animals and plants. I started to research and wrote a big article for one of Germany’s most popular monthly magazines, Cicero. This became the first chapter of the book.

What were some of the most fascinating stories you investigated for Animal Internet? What were the most memorable of the locations you visited and the animals you saw?

Some years ago a big brown bear turned up in the village where I live. He came from Italy, crossed two borders and some highways and started to ramble around in the Bavarian Prealps. People weren’t amused because this bear, dubbed Bruno by the media, killed sheep, ate honey and strolled through the streets at dawn. Finally he was killed by hunters because nobody was able to catch him. Today Bruno stands as a trophy in a Munich museum. The whole affair was a big scandal because it showed the distance between people and nature in modern Europe. In the book I retell the story and ask: What would have happened if Bruno had been tagged? What would be the attitude of the public if it could follow this predator in real-time on Facebook and YouTube? Some other fascinating stories were the rescue of the Saiga-Antilopes in Kazakhstan—this mammal holds the sad record of being the mammal to go extinct the fastest (this was due to the political breakdown of the Soviet Union and the ensuing anarchy)—and the way Californian and Australian oceanographers are protecting surfers and divers from the great white shark by a sort of digital warning system that’s connected to Twitter. But these are only a few of the many fascinating animal stories ranging from tagged butterflies to whales which I tell in the book. With the Animal Internet nature is telling it’s own story.

Were you putting on a brave face in the book, or do you really believe that the digitization of animals is our only hope to save them?

Let me put it this way: I am a huge fan of the real wilderness. I live in the mountains (okay, the Bavarian Alps are not the Rockies, Munich is only 100 miles away, but my wife who used to live in Paris thinks that we live in the wilderness), I like hiking and skiing, and when I’m out in nature I hate people playing around with their stupid smartphones. I am very much analogue out there. This was my starting point. But when I started talking to experts, park rangers and zoologists who really cared about their animals, I gradually understood that the mysterious opacity of nature which we hold up as romantic ideal actually is killing animals. Because you can’t protect what you do not know. You’re even less like to care about animals or to donate to a rescue fund if you are not able to follow the story of their lives. So, at the end of the process of writing the book, I came to the conclusion which is pretty much backed up by famous and influential scientists like Professor Martin Wikelski (who is the successor of Konrad Lorenz) and Professor Josef Reichholf, that analogue and digital must merge in order to create a new space of nature in which the positive, empathic, loving relationship between mankind and creation is the most important condition for the survival of most of the species. And the Internet is the key to this new space. So, theologically speaking, one could say (as has been done before by media thinkers): It looks like the Internet is God.

You speak a bit about climate change in Animal Internet; in your view, is that the greatest threat facing animals today? And will any amount of digitization and tracking be enough to stop humans from polluting the earth into extinction?

No, I don’t think so. Climate change will only transform the structure of the world’s fauna. Some species will disappear, others are benefiting from climate change and global warming. Nature reconstructed itself after the ice age. Creation is resilient. I see a much bigger and much more direct risk in man’s ineffable urge for growth, in the mental structure of our modern societies which has them hurtling towards the destruction of the environment. Climate change will not kill gorillas or orangutans, but deforestation will. Digital tracking is a feeble measure against this global bulldozer. So the book definitely has a melancholy note.

You have a chapter in your book that deals with house pets—we love our dogs and cats more than ever, and spend billions of dollars a year on pet-related products. Do you think that the increasing closeness of humans to our pets obscures our views of animals in the wild, to the detriment of the latter?

That is definitely so. We look at house pets more as family members, as parts of a social structure than as animals. Every dog species once had a duty, at least in old Europe. Dalmatians escorted stagecoaches, Schnauzers protected breweries, Rottweilers cleaned up stockyards. This is all long gone. Today we choose a dog not because of his abilities (agility excepted) but because of his shape, color and so on. We make an aesthetic decision—as if we are picking out a new table or TV set. This has nothing to do with the substance and essence of nature which used to be present in the way people looked at farm and working animals all through history up to the beginning of World War Two. Then came technology, and it was all was gone.

You mention the popularity of bird watching in the book. Several prominent American authors—Jonathan Franzen, James Wolcott, Jonathan Rosen among them—are avid birders and like apprising their readers about their sightings, making it seem like bird watching has replaced baseball as the eggheads’ favorite sport. What’s going on here?

Birding is an old discipline. It started with Aristotle and used to be an aristocratic pastime especially in Great Britain. So there are two ways to explain the current fashion for sitting still and gazing at water birds who all look identical through $2,000 binoculars: The first is that we are bored with postmodern abstraction and want to go back to basics; we want to reconcile with our ancient roots (Aristotle). The other explanation would be: Americans especially are bored with democratic mass civilization and want to turn into real Englishman again with Barbour jackets and gumboots. Like: “My inner self is actually Sean Connery!” or “Make America English Again!” This seems to me the background and significance of these eggheads crawling through the wilderness and counting ducks. And this might also explain the shift from baseball to birding (B2B): Birding is as much impregnated with statistics as baseball. You count, you make lists, you share your numbers. And Birding versus Baseball has an added benefit: It’s healthier for the egghead.

You’re a German author whose book has now appeared in English. Do you have a sense at this point about the differences in how the tracking of animals is received in the United States versus Europe?

Sure. Very much. Europeans are technophobes. Americans are technophiles. In Germany we are curbing our use of nuclear power and going back to the Middle Ages in terms of energy production. The European equation reads like this: technology = risks. The U.S. equation reads: technology = chances. So it’s no wonder that the leading guy, even the “inventor” of the Animal Internet (the term stems from me, the technology from him), Martin Wikelski, used to work at American universities before coming to the Max Planck Institute. That’s where he developed his vision of a new zoological discipline of monitoring animals from outer space by GPS. He has a lot of trouble with German colleagues and environmentalists who believe that the new transparency of nature represents more of a risk than of a chance. And then there is the European obsession with data security. We are already talking about data protection for individual animals. All this is patent nonsense because why should we care about the data set of a sea turtle which our ignorance has killed? I would recommend these ecological conservatives read Animal Internet. There they will find the future of humanity and nature.

Upcoming events with Alexander Pschera

Alexander Pschera, author of Animal Internet: Nature and the Digital Revolution, will be reading at the following venues. Check back here for more updates on Animal Internet:

Monday, April 18

6:30-8:00 pm

NYU Deutsches Haus

42 Washington Mews, Greenwich Village

New York, NY 10003

http://deutscheshaus.as.nyu.edu/object/io_1458742280549.html

Tuesday, April 19

5:00-6:30 pm

St Agnes Branch of the New York Public Library

444 Amsterdam Avenue and 82nd Street

New York, NY 10024

http://www.nypl.org/events/programs/2016/04/19/author-talk-alexander-pschera-animal-internet

Tuesday, April 19

7:30-9:00 pm

Alchemist’s Kitchen

Discussion with David Rothenberg

21 East 1st Street, Lower East Side

New York, NY 10003

http://www.thealchemistskitchen.com/pages/events

North and East

Sergei Lebedev is the author of Oblivion, The Year of the Comet, The Goose Fritz and Untraceable.

One day, on a cold winter eve, my father took his rifle down from the rafter to clean it. In answer to my unspoken request, he took out, from under the ceiling of the apartment, tightly bundled heavy canvas sleeping bags, a threadbare, faded rucksack, marsh boots, smoky mess kits, an officer’s field desk for maps, and a geologist’s hammer—his expeditionary equipment. While he took apart the rifle and cleaned the barrels with the ramrod, I, who had never been farther than the dacha, looked at these items from his past—and I knew who I’d become when I grew up, where the blue arrow of the compass, with its cracked leather strap, would take me.

North. And East.

I don’t know or remember what my peers dreamed about. My book of desires was a geographical atlas of the USSR, a giant folio with maps on the scale of 1:2,500,000, twenty-five kilometers to one centimeter. I’d open at random to a page with a map of the Transbaikal or the Archangelsk region, drink in, swallow from the pages the names of rivers and mountain ranges, distant islands in the polar seas; I’d imagine where I’d go, alone in a dark valley, along susurrus rivers in the fog, with clear stars climbing above the glaciers at the foot of a gorge. Neither my friends nor my comrades appeared in these dreams. Only untamed spaces, and their calling out to me.

North. And East.

My parents’ friends used to gather at our apartment—the same geologists, geophysicists, the staff from polar expeditions. They held conversations over vodka, sang songs—the songs you wouldn’t hear over the radio, songs of the camps, songs of the arrestees. And an icy chill from the faraway places would blow over the table, over the simple snacks and the shot glasses, and the air of celebration abated, as if the others at the table saw what I couldn’t see—some sort of frozen abyss, where people disappeared without a trace; a dark ill-boding secret arose behind snatches of words about the abandoned barracks, exiles who were enlisted into labor, about the unknown graves.

What could I comprehend of this? Nothing. But those far-off evenings, those voices, they did something to me, mingling with the inner whisperings of blood; something further sharpened, further aimed the arrow of the compass: North, and East.

There was only one figure of childhood that was able to, if you will, divert the arrow. At my grandmother’s house—my mother’s mother—there was a hefty box of war decorations and medals. It weighed a kilogram or two. The Order of Lenin, two Red Banners, two Red Stars, countless medals; sometimes I was allowed to look at them, hold them in my hands, my fingers growing numb. My grandfather, first husband of my grandmother, was a company commander in Stalingrad, and I always knew, though nobody ever told me, that these were his decorations, the decorations of a true hero.

When nobody was looking, hesitating out my own impudence, I would pin one of the orders onto my shirt and stand in front of the mirror. And I no longer saw mountain valleys, but frozen ditches, oncoming German tanks, black smoke, misty, snow-covered fields. There was probably nobody who was more Soviet than I was at that moment, a ten or eleven year old kid, frozen in front of the mirror wearing somebody else’s—though mine, too, in a way—medal, which was pulling comically on the pocket of my child’s t-shirt.

To fight and die for one’s country; to adapt somebody else’s biography as your own—a child of the last generation of the Soviet Union, I was still open to its heroics, its myths, its hagiographies, behind which I didn’t suspect the possibility of deceit.

This ebbed when I was a teenager, of course, but still something remained deep in me: like honor or pride, like a feeling that you’re a purposive link in the chain of generations.

And then, life determined what came next—which arrived like a telegram, a sign from my own personal future, too massive to understand it at that age.

At fifteen I set off to work on my first geological expedition—there, to my coveted North, to the promised land of the East. In the city of Pechora we plunged into a helicopter to fly to the pre-polar Ural Mountains. The old Mil helicopter took off roughly from the field, gained speed, gathered height, and the striped, prison-camp color scheme of the heat electropower station flashed by, and jagged clouds, a sliver of Pechora with the scattered logs of tree felling on the shoals—and all the sudden, just like an irregular heartbeat, the entire taiga opened up for tens of kilometers all around.

There was a strange bald patch that could be seen in the middle of the taiga, half overgrown roads and toy-like houses (from the distance), with caved-in roofs, grey and black, decorated by light lilac-covered smears. Smears the color of fireweed, the plant that grows on fire sites and vacant lots. And all of this—again, from a bird’s eye view—came together into a certain scheme, an architectural draft, as if an invisible hand had scattered them all across the taiga, united by roads, decayed bridges over rivers.

There was a strange bald patch that could be seen in the middle of the taiga, half overgrown roads and toy-like houses (from the distance), with caved-in roofs, grey and black, decorated by light lilac-covered smears. Smears the color of fireweed, the plant that grows on fire sites and vacant lots. And all of this—again, from a bird’s eye view—came together into a certain scheme, an architectural draft, as if an invisible hand had scattered them all across the taiga, united by roads, decayed bridges over rivers.

Not believing, not wanting to believe, I looked at the second pilot through the open door of the cockpit. Understanding my question, he shouted in a loud voice, to block out the roar of the turbines:

“That’s a camp! A former camp!”

I’d already read Shalamov and Solzhenitsyn, already understood what was being discussed around my parents’ table as a child. However, being born in Moscow, living in Moscow, I never thought that the camps existed in the same times as I did; in my time. They had to do with the deep past, the era of my parents’ youth, and it was impossible to imagine them in 1996.

When you’re on a helicopter that’s in flight, the scariest thing of all is to hear silence. That means water’s gotten into the fuel line, the turbines have stalled, and the propellers have begun to windmill.

But at that moment I heard silence. No, the turbines hadn’t stalled, there was a terrible vibrating din, but I was cut off from it all, I’d been tossed into another dimension. I sat on the seat at the side window looking down and I was sealed in a capsule of silence, was one on one with myself, just myself. I felt I was a witness, that life had changed irrevocably simply because I had seen what I saw.

Then there were seven years of expeditions; the same North and East. Deserted mines and adits, rusty rails and train cars, rotting wooden boards of former barracks, old caravan trails, sunken in the yielding tundra earth by the hooves of packhorses. We walked the areas of the former camps, gathered samples of minerals for museums there, where once inmates had labored.

There weren’t enough of us and in order to cast our wide net without gaping holes over the huge area, we walked solitary routes, a strictly prohibited technique for safety reasons. Why do I mention this? Because, of course, later this would tell upon our fate: the feeling when in the morning you lace up your boots at the campfire, and around you are the voices of your comrades; but by the time you’ve finished tying them, you take a step and you’re alone already, only dispassionate nature all around, and whether you’ll make it through depends on you.

You’re alone, and nobody will help you.

I believe this feeling helped me back then. Then, when the North and East let me go, released me, all of the sudden I felt they’d given me everything I needed, and further expeditions would simply be repetition.

My grandmother died. I went to her apartment, to get her papers in order.

My grandmother had two husbands—one, my real grandfather, the same one who was the company commander in Stalingrad, and a second one, who died when I was six months old. I didn’t know anything about the second one except his name—Aleksandr Ivanovich—and what he left behind: two fishing rods, a hat, and a folding chair, stored in the attic at the dacha.

Among the papers I found two officer’s ID booklets. I remembered how in childhood I imagined myself as the descendant of a grandfather-hero. And, spurred by curiosity, I opened the ID card of my grandfather Grigory.

But there was nothing noted in it except a medal “For Victory over Germany”—a medal given to everyone who participated in the war.

Already standing stock still, I opened the second ID card.

Aleksandr Ivanovich Erkin.

Lieutenant Colonel, B.Ch.K. (All-Russian Special Commission for Counter-Revolution and Sabotage); OGPU (Joint State Political Directorate); NKVD (People’s Commission of Internal Affairs); MGB (Ministry of State Security).

Did not fight in the war.

Was awarded …

All of these orders and medals belonged to him, my grandmother’s second husband, an executioner and murderer, twice decorated in 1937, the year of the Great Terror.

And I stood with two cardboard ID booklets in my hands, cursing myself, cursing my parents—yes, they knew whom the medals belonged to in reality, and they were silent. I stood, understanding why I wandered through the North and East, for what reason I’d seen the ruins of the former camps, stood at the foot of the unnamed graves—in order to write a book.

A book for those like me, who will one day open their family archive—and find there something completely different than what they expected.

—Sergei Lebedev