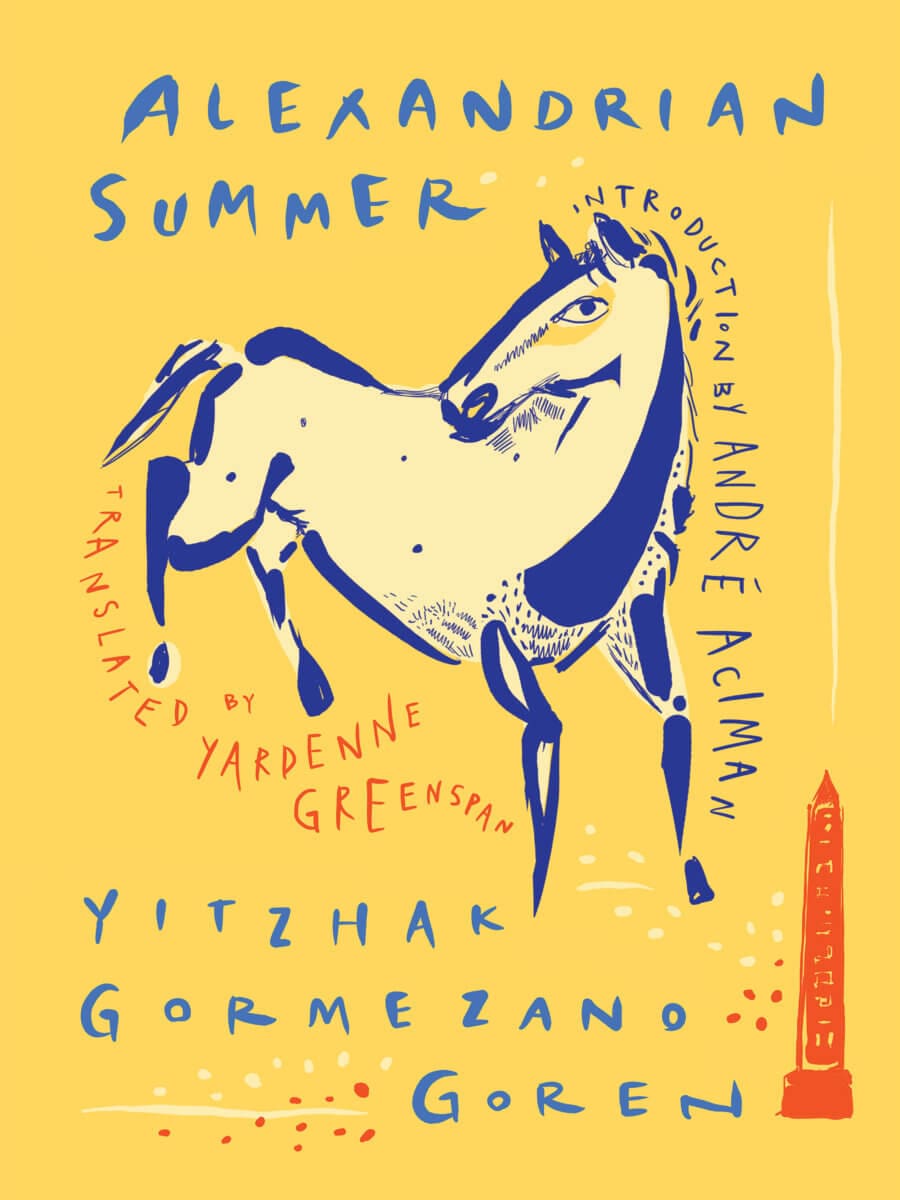

Alexandrian Summer is the story of two Jewish families living their frenzied last days in the doomed cosmopolitan social whirl of Alexandria just before fleeing Egypt for Israel in 1951. The conventions of the Egyptian upper-middle class are laid bare in this dazzling novel, which exposes startling sexual hypocrisies and portrays a now vanished polyglot world of horse racing, seaside promenades and elegant nightclubs. Hamdi-Ali is an old-time patriarch with more than a dash of strong Turkish blood. His handsome elder son, a promising horse jockey, can’t afford sexual frustration, as it leads him to overeat and imperil his career, but the woman he lusts after won’t let him get beyond undoing a few buttons. Victor, the younger son, takes his pleasure with other boys. But the true heroine of the story – richly evoked in a pungent upstairs/downstairs mix – is the raucous, seductive city of Alexandria itself. Published in Hebrew in 1978, Alexandrian Summer appears now in translation for the first time.

The novel features an introduction by André Aciman, author of Out of Egypt and Call Me by Your Name.

Excerpt from Alexandrian Summer

1. From Twenty Years Away

The Sporting Club neighborhood, the horse racing tracks beyond the tramlines. At the intersection of Rue Delta and the Corniche, by the sea, stands house number twenty-four, all seven of its stories (we used to climb up to the flat roof and shoot paper arrows down at the industrious ants running around on the sidewalk, back and forth, as if there were purpose to all this frenzy).

An Arab doorman, Badri, stands guard, squinting at the sun. His face is tan and emaciated. His little boy, Abdu, loiters at his side, helping him watch the shadows stretching over the sidewalk and the passing cars, headed toward the sea. Badri and his son welcome anyone approaching the building with an alert greeting, “Ahalan, ya sidi,” full of expectation: will the guest give bakshish or not? If the guest does tip them, they escort him with bows all the way to the elevator door. If he doesn’t – they point lazily in the direction of the moldy duskiness.

The elevator is ancient, barred with black metal and faded gold openwork, and bitten by reddish rust. The door slams with a metallic shake, and … a miracle! The elevator rises with a buzz, dragging with effort a looping tail that grows longer as the elevator ascends. Chilling stories have been told about power outages between the fourth and fifth floors; fights between neighbors, beginning in the stairwell, intensified in the gloom of the elevator, later to dissipate outside, in the subtropical sun that ridicules all human endeavors.

Second floor, that’s as far as I go. If you aren’t lazy, you could climb it by foot. A copper plate bearing the name of a Jewish family, descendant of Sephardic Jews from the era of the Spanish Expulsion (their last name is the name of their home town with the suffix “ano”). The doorbell rings. A dark-haired and skinny servant opens the door and addresses you in lilting Mediterranean French: “Oui, missier, quisqui voulez?” and you stutter and ask: “Is this where Robert … Robby lives?”

The servant is surprised that a thirty-year-old man is interested in a ten-year-old boy, but he does not voice his opinion as long as he isn’t asked to. “Robby – there!” He signals towards the balcony, at the far end of the apartment. “Should I call him?”

“No, no! Please, there’s no need.”

The Arab servant looks at you with a hint of suspicion. “Who you, missier?” and you give him your name, Hebraized to fit Israel of the 1950s, which rejected all foreign sounds. The servant does not decipher any connection between the two names. To him the strange name could be Greek or Turkish or Italian or Maltese or Armenian or French or British or even American. Alexandria is the center of the world, a cosmopolitan city. You want to add: yes, I used to be Robert too. Twenty years ago. I’m coming from twenty years away. I won’t interrupt, I just want to watch. I won’t interfere, God forbid. No one will notice me. I just want to tell the story of one summer, a Mediterranean summer, an Alexandrian summer.

- A Family from Cairo

Waves of memories of that city – Alexandria – rise and recede. The story of the Alexandrian summer does not present itself easily. It is wrapped in layers of nostalgia, of oblivion, of generalizations. I search for the objective, the distinguishing. Should I tell it in first or third person? Should I use real names or give my characters aliases, adding a note along the lines of “any resemblance to real persons is purely incidental”? These may be small details, but they are the ones holding back my pen.

I want to tell you about the Hamdi-Ali family. What is it like, really, this family? The Hamdi-Ali family embodies joie de vivre, the unending Mediterranean energy. Yes, Mediterranean. And maybe it’s because of this Mediterranean-ness that I’m sitting here, telling this story. Here, in Israel, which feels much more like Eastern Europe to me. I might as well be sitting on the shore of the Baltic Sea, for all the distance I feel from the Mediterranean, which can be seen from my window in Tel Aviv. That’s why I am eager to tell the story of the Hamdi-Alis, and the story of Alexandria. A Jewish family from Cairo that came to Alexandria to spend a summer of joy. Alexandria of the days of King Farouk, with his hook-mustache and his dark glasses, the Alexandria I knew as a child, this Alexandria, which has been feeding my imagination for over twenty years, from the day I left it on December 21st, 1951, when I was ten years old.

A storm brewed as we sailed from the port toward the lighthouse, and didn’t stop until we reached the shores of Italy. There, we were welcomed by Christmas snow. Winter was at its peak, but me, I wish to tell the story of a summer, a summer in Alexandria, an Alexandrian summer: vacation, horse races, sailboats, fishing for sea urchins, swallowing crabs, platonic (and not so platonic) romances, traffic jams, traffic jams, traffic jams, honking, honking, honking of cars and cars and more cars. All rushing toward the Corniche, the busy road overlooking the sea, where vacationers at the beach rented shacks so they wouldn’t be forced to undress in the public dressing rooms with “all those Arabs.”

- The Royal Family

Car. Car. Truck. Motorcycle. Another car. Yes, he made it! He got it down. Next: no point in listing a bicycle. Another motorcycle. Yes … it’s hard to see the license plate number from the balcony – but he has it down! What a beauty – there’s a luxury car. Quick, write down the number. De Soto, Chrysler, Lincoln-Continental. When they approach the intersection they are forced to slow down and then he can write down their numbers. And if there’s a traffic jam he can even rest for a few seconds. What a festival of sounds!

“The summer in Alexandria is a nightmare!”

“I don’t understand, why aren’t drivers forbidden from honking in urban areas? Don’t give me that look. In any civilized city in the world …”

“What a cacophony! I’m about to lose my mind.”

“If you think Cairo’s any better, my dear, you’re mistaken, ma chère. When you approach the Qasr-al-Nil Bridge, the honking can even wake up the Pharaohs in their tombs!”

“Yes, but in Paris …”

“And in London …”

Those grownups! Living in Alexandria. Most of them born there. Arabic? God forbid! French, sometimes English. Looking askance with coquettish flirtation at the fashion hubs of Europe, making a commendable effort not to lag behind the dernier cri from Paris, London or New York. Especially the women, as they sit around playing rummy. Robby often eavesdrops on their conversations. He’s the youngest, much younger than his older siblings. Mostly solitary. No, not a tragic loneliness of the kind that gives birth to reclusive poets – nonsense, he has friends his age. But he can’t spend all day at their houses or have them over at his. In Alexandria, middle class children do not play in the street, heaven forbid.

And so he invents all sorts of strange games.

“Well, boys, is your mission clear? Whenever a car passes, you take down its license plate number. Look alive, boys, stay on your toes. If you notice any suspicious movement, report to headquarters immediately! Okay, at ease!” Perhaps these orders were spoken in some Hollywood film he saw in one of the theaters on Boulevard Ramleh? Or perhaps he just made up some sort of rationale for his bizarre obsession with taking down the license plate numbers of passing cars?

“What are you writing-writing-writing down there in your notebook all-the-time-all-the-time, Robby?”

“I’m, uh …”

“And most importantly boys, maintain secrecy! Never reveal your mission.”

“Uh, uh, I’m not writing, I-I-I’m … uh … drawing.”

“Oh, Livia, you have to see Robby’s drawings, a real talent. When he grows up, he’ll be an architect. Robby, come show Madame Livia your drawings.”

“Later … later … I’m, uh, busy right now.”

“He’s busy. He’s busy. He’s busy!” They laugh amongst themselves. Not even ten yet, and he’s busy! Does he shop at the Hanneaux department stores, like us? No. Does he play cards, en-matinée, like us? No. Must he rebuke the servants from time to time, like us? No. Then what is he so busy with? “It’s your turn, Geena darling.”

“Thank you.”

Writing down and cataloging cars – that is a task for summer days. In winter: a raging wind, rain, hail, school. The balconies in Alexandria are open. No shutters and no blinds. The apartments are sprawling and no one is in need of an extra room, and so the balcony is a balcony, open to the gale that revolts in winter, and to the rays of sun, searing and burning in summer. They say you can bake a pita on the stones of the pyramids. But Alex is cool and temperate. Reminiscent of …

“What are you talking about? Capri! Really! How can you even compare them?”

“Who can afford to go to Capri or the Riviera every year?”

“That’s why they all come surging here in the summer.”

A 1940 Topolino. The screeching of the brakes. A belch, a hiccup, a moan, pulling up, right below the balcony. Robby doesn’t even get a chance to take its number down. Three cars pull up behind it. Three next to it. Another traffic jam! Curses in all the languages of the Mediterranean. No one can compete with the Greeks for a good swear word! And honking, honking in all scales.

David Hamdi-Ali, tall as a toreador, blond as a Nordic cavalier, elegant like Rudolph Valentino, leaps with agility in his supple white leather shoes, subduing the drowsy virus whose journey through his body has finally run its course to conclude with a series of asthmatic coughs. David ignores the swearing and the cursing, and even responds to the threats with Olympian serenity. How can they know that, on top of everything else, he’s also a “dirty Jew?” He opens the car door for his mother, Emilie, with a light bow, expressing his love and adoration. From the moment her feet touch the sidewalk, he ignores the other passengers, his father Joseph and his brother Victor. The eleven-year-old boy filters out, looking around with suspicious, coveting eyes, fixing his gaze on all passing women, with no regard to age or race. Before he even knows which way is up, he receives a blow to the back of the neck, his brother hissing at him: “Stand up straight, moron!” This is simply the nature of things: David was born a prince, and he won’t tolerate his brother, with his infuriating habit of sticking out his neck and rolling his watery eyes, ruining the image of his family. Victor, just like his big brother, is wearing a white summer suit, but on him it looks like a tattered sack. It is strewn with wrinkles in back and filthy in the front, like the face of an old Arab woman from a forgotten village. David drove the Topolino for more than six hours in the blazing summer heat, yet he emerges from the car ironed and spotless. You’re born this way. Emilie adjusts the fluttery white net that slides down her wide-brimmed hat – an entirely superfluous gesture, seeing as how the net had already been sloping at a natural, graceful, elegant angle. You are either born a queen, or you are not born a queen. Joseph wears a wine-colored fez which seems too big for his head even though it is not. His clothes also seem to hang on his body. Some souls are at home in the world, while other souls … Joseph sighs and shakes his head, and the red fringe of the fez swings with each shake.

Stretching their bones. Six hours in that Topolino … It’s a wonder it didn’t break down in the middle of the desert. David drives it as if it were nothing less than a Rolls-Royce, but one has to admit it’s slightly less comfortable than that. Ahhhh … what a wonderful breeze from the sea! This is Alexandria! There, that’s the apartment, on the second floor, you see, Victor? Victor, stand up straight, you idiot! That kid over there, that’s Robby. You’ll be friends! Waving. Yes, Robby answers with a wave and disappears from the balcony, running to announce to his parents: “The Hamdi-Alis are here! The Hamdi-Alis are here!”

Salem, the servant, is sent down to help carry their luggage. Robby trails behind him. The notebook remains on the wall of the balcony. The wind flips through the pages, not understanding the meaning of all these numbers, numbers and more numbers.