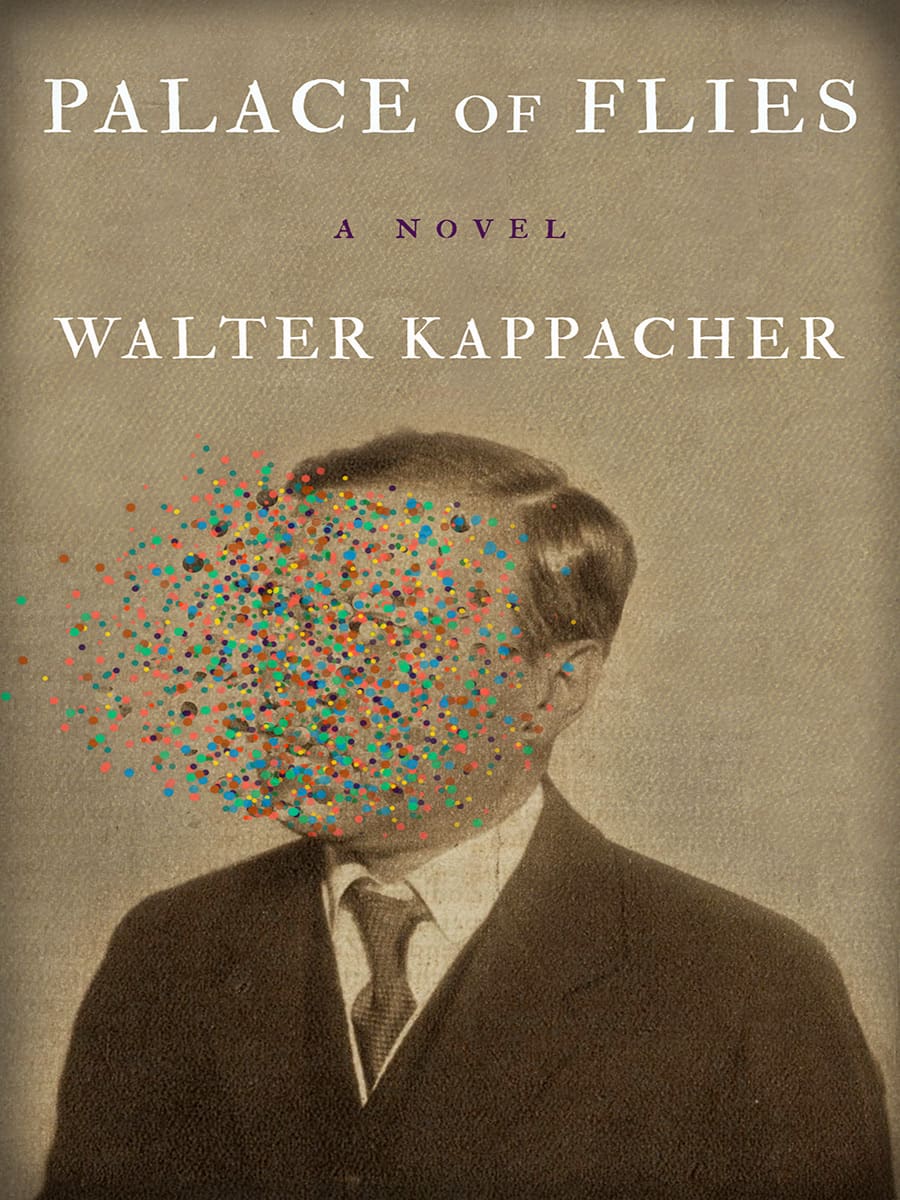

This absorbing, sensitive novel portrays a famed author in a moment of crisis: an aging Hugo von Hofmannsthal returns to a summer resort outside of Salzburg that he visited as a child. But in the spa town where he once thrilled to the joys of youth, he now feels unproductive and uninspired, adrift in the modern world born after World War One. Over ten days in 1924 in a ramshackle inn that has been renamed the Grand Hotel, Hofmannsthal fruitlessly attempts to complete a play he’s long been wrestling with. The writer is plagued by feelings of loneliness and failure that echo in a buzz of inner monologues, imaginary conversations and nostalgic memories of relationships with glittering cultural figures. Palace of Flies conjures up an individual state of distress and disruption at a time of fundamental societal transformation that speaks eloquently to our own age.

With an introduction by Michael P. Steinberg, professor of history, music, and German studies at Brown University.

Excerpt from Palace of Flies

On one of the first days, he wondered whether he might have grown too old for this place, which had been a source of conflicted feelings since childhood. Had his memory of the happy days and weeks here, all those years ago, played a terrible trick on him?

What in Bad Fusch was now called the Grand Hotel was, in fact, a third-rate hotel, really an inn but only slightly more distinguished. In earlier days, of course, in the nineties, around the turn of the century, his family and even the more coddled guests of the monarchy’s summer resorts had not been as demanding as they were today. Often, they had lodged in the bedrooms of farmers, who in turn slept during the summer in the attic.

Now I have this half-full chamber pot under my bed, it occurred to him, and there is no bell, let alone a telephone, to call Vroni or Kreszenz. Why didn’t I stay in Lenzerheide, with dear Carl? The room had been fine, the food first-rate. Swiss, plain and simple: there, the wretched war had not ruined everything. Unlike what he had imagined in Lenzerheide, however, he was as incapable of working in the Fusch as he was in Switzerland. Thus far he had been unable to use the undisturbed environment here to his work’s advantage.

On the contrary, the best thing here in the Fusch had in fact been his acquaintance with Doctor Krakauer, and he very much hoped that it would not break off now—that would be too harsh a punishment for his faux pas. It had been three days since Krakauer disappeared from the face of the earth—on the other hand, he himself had been sitting in his room for the most part, at a little table by the window, unable to believe that his imagination, his associative faculties, have once again completely abandoned him.

He pondered further: actually, I owe it to my circulatory collapse that I met Krakauer—a wonderful fluke of fate that he happened to pass by!

He would never forget the view through the delicate branches, the radiant crown of the . . . beech tree, probably . . . tiny veins, the lines of life . . . or maple? How the leaves shone, some golden, most green. How many things swept through my head in that moment? Five days it has been—or four?

“It seems to me that you are able to sit up; would you like to try that? I will help you, if I may.”

A young man, gray-green loden jacket, held my hand . . . apparently counting the beats of my pulse. With the other hand he placed a hat, my hat, in my lap. I had lain on the ground like this once before, some years ago . . . in front of a garden gate. In Altaussee, in front of the villa of Baroness . . . Lhotsky.

“Are you feeling dizzy?”

The cane the young gentleman was holding was mine. What happened?

“Breathe,” he said, “breathe calmly.”

An elderly couple in their tracht, who had been standing next to the man, now moved away.

He had seen this face once before. Had it been the previous day? If he remembered correctly, in the company of . . . an elderly lady, this man’s mother perhaps, wearing a hat with a lavish brim. From some distance, he heard the sound of a postal omnibus’s engine revving, struggling up the mountain road.

“Your pulse . . . Allow me.”