In 1776 Fanny von Arnstein, the daughter of the Jewish master of the royal mint in Berlin, came to Vienna as an 18-year-old bride, bringing with her the intellectual sharpness and vitality of her birthplace. In her youth, she was influenced by the philosopher Moses Mendelssohn, a family friend who spearheaded the emancipation of German Jewry. She married a financier to the Austro-Hungarian imperial court, and in 1798 her husband became the first unconverted Jew in Austria to be granted the title of baron. Soon Fanny hosted an ever more splendid salon which attracted the leading figures of her day, including Madame de Staël, the Duke of Wellington, Lord Nelson, his lover Lady Hamilton and the young Arthur Schopenhauer.

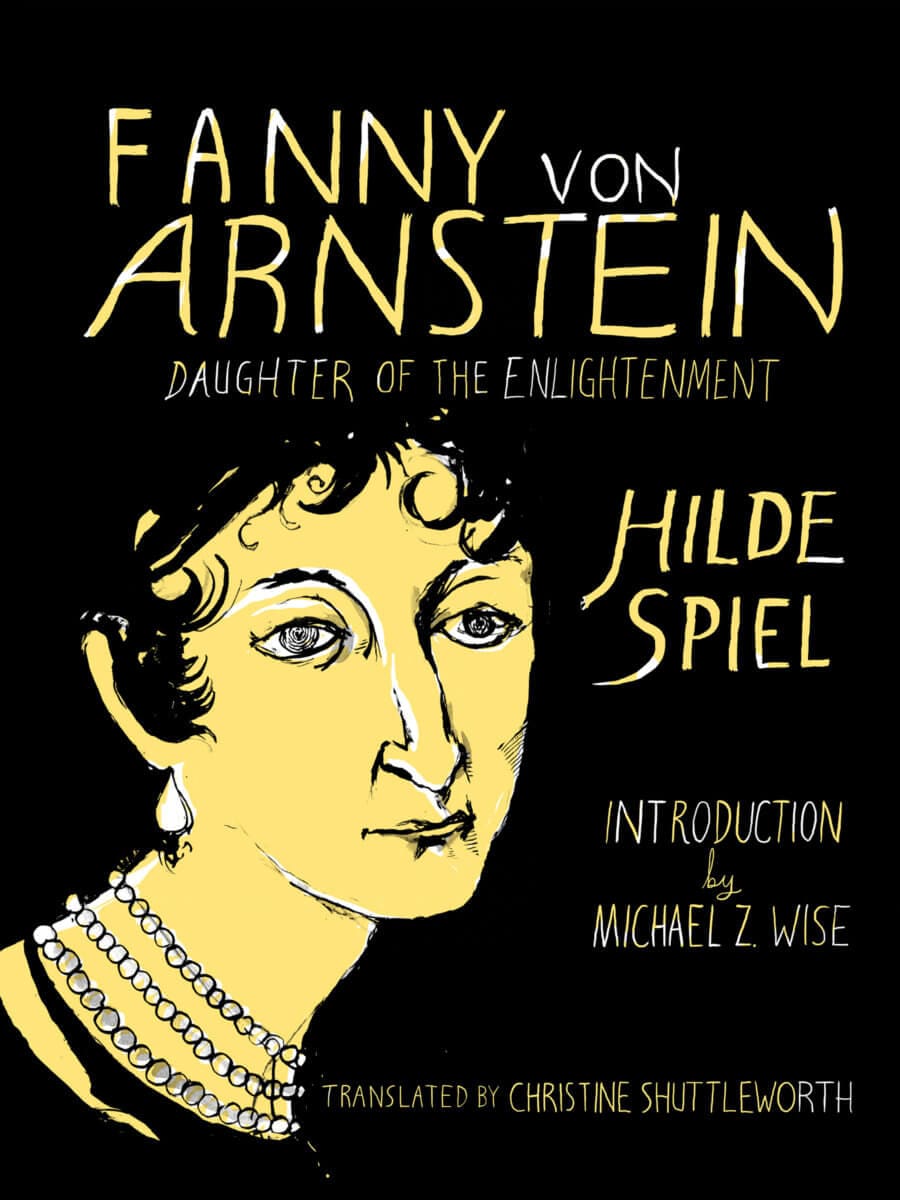

Spiel’s elegantly written and carefully researched biography not only provides a vivid portrait of a brave and passionate woman who advocated for the rights and acceptance of Jews but illuminates a central era in European cultural and social history.

The biography features a critical introduction by Michael Z. Wise, an American author and journalist who has written extensively about Central European culture and spent five years as a Vienna-based correspondent for Reuters and The Washington Post.

Excerpt from Fanny von Arnstein: Daughter of the Enlightenment

And so, shortly before her death, Maria Theresa was still intent on “reducing the numbers of the Jews here, and by no means, on any pretext, increasing them further.” At that time there were ninety-nine families in Vienna, among whom were twenty-five tolerated ones, with children and servants amounting to not more than 520 persons in all. They had much to expect from the demise of the Empress and the accession of Joseph. Yet they uttered no word of complaint or of hope, but knuckled under and kept their counsel, while the dissension of officials raged over their heads. From their ranks no request or petition penetrated to the ears of the government. On the other hand they took part, as far as they were allowed, in the destiny of their country and the rise of their city.

They sighed when another quarrel with Frederick sprang up over the Bavarian succession, and breathed again when peace was declared after ten months’ bloodless war. They strolled in the Augarten which had been opened to the public, and visited the playhouse recently raised to the rank of “Imperial and Royal Theater” (the Hofburgtheater). They admired the new paving, in tessellated granite, on both sides, of the most important streets in Vienna; they enjoyed the splendid festivals that were held so frequently both in winter and summer, the sleigh-rides of the nobility, the solemn processions, the fireworks in the Prater; they flocked to the column of the Trinity in the Graben for the centenary commemoration of the end of the Great Plague; and they were frightened out of their wits when, a few days later, the great powder-magazine on the outskirts of the city blew up and destroyed a number of houses. Vienna was their home; they knew no other and professed their loyalty to her, even if their love was only seldom returned.

The Empress meanwhile had grown fat and sluggish, could hardly walk and had to be carried by machinery on a green morocco-leather couch to her apartments in the Hofburg and to the balcony of the Gloriette at Schönbrunn. In the autumn of 1780 she contracted catarrh of the chest. Her faith, which had made her as good and happy as she was intolerant, helped her to endure the pain and contemplate her death with dignity. She sat in her arm-chair, surrounded by her family, patiently waiting for eternal bliss. About nine o’clock on the evening of 29 November she breathed her last.

On the same day, in Berlin, whither she had traveled for her confinement, Fanny gave birth to a daughter.

It was presumably on the first, if certainly not the last, of her visits to her parental home, that little Henriette was born to her. Whenever she lost her taste for the mild air of Vienna, the soft tones of its conversation, its leisurely way of thinking, Fanny betook herself to Berlin, to enjoy its brisk wind, sharp outlines, cutting wit and agile comprehension. She refreshed herself in the circle of her clever sisters, two of whom, Cäcilie and Rebecca, were later drawn into her circle and settled in homes near hers. And she enjoyed her reunions with her brothers, although they did not possess in the same measure the circumspection and farsightedness of her father. Her eldest brother Isaac, like his brothers Benjamin and Jacob, had married a cousin from the house of Wulff, just as Cäcilie had taken a maternal cousin for her first husband. With these and numerous other in-laws Fanny had a widely ramified family, which flocked around her whenever she visited the Prussian capital. Moreover, she found in Berlin what she herself was hoping to establish in Vienna: the beginnings of the literary salon.

Under Frederick the Great, court and society had become highly Francophile. Their teachers were Parisian philosophers; Frenchmen had set up the new grammar school, and the King had appointed Maupertuis as president of the Berlin Academy that had been founded by his grandfather. The example of a constant social interchange of thought, of the cultivation of learned conversation, had come from Paris and had incited imitation. The assemblies at the houses of the Marquise du Deffand, the Marquise d’Epinay, Madame Geoffrin and Mademoiselle d’Espinasse were beginning to find followers among the Prussians. The nobility, to be sure, still hesitated to give up its formal receptions, and the bourgeoisie, lacking a feeling for higher culture, held fast to “the simplicity of the household according to German custom.” It was, therefore, left principally to Jewish circles to unite art and society according to the Parisian model. They possessed gifts which allowed them to conform to French culture more speedily than their compatriots — “true intellect, wit and taste, the refined expression of refined concepts, a mocking tone and a speedy perception of the ridiculous, and finally the instinct of a certain practical rationalism in their way of life.” With their growing prosperity they were able to gratify their aspirations towards knowledge and wisdom, to recognition of what was true and possession of what was beautiful, and it was at their gatherings that liberal people of noble birth, whose families and usual social contacts offered them little stimulation, were beginning to assemble. And so, as a later observer expressed it, there developed “a quite original intellectual atmosphere in Berlin, a mixture of Jewry, of the ‘enlightened ones,’ as our ancestors called them, and a kind of Gallic Atticism.”

One of the first houses in which such circles developed was that of the councilor Benjamin Ephraim, who, as the youngest son of the mint-master, raised his controversial name to deserved honor. As early as 1761 he had gone to Amsterdam to set up a business house in association with his father’s firm, had there married a rich heiress and shortly afterwards returned with her to Berlin. Now he was establishing an art collection in his city mansion which was in no way inferior to that of Daniel Itzig and included paintings by Caravaggio, Poussin and Roland Davery. His splendidly decorated apartments were visited, if not yet by persons of rank, at least by some who were noteworthy. In the 1780s his nieces Sophie and Marianne Meyer, later to become respectively Frau von Grotthuss and Frau von Eybenberg, introduced young sons of old families into his house, after first gaining entry to the upper social circles through their early conversion to Christianity.

But Benjamin Ephraim, like Daniel Itzig and the far poorer, though considerably more highly honored Moses Mendelssohn, in whose houses the beginnings of an “intellectual Berlin” had likewise formed, was by no means able to unite the higher reaches of society with those of poetry, politics and science, as a series of talented women succeeded in doing one or two decades later. When Fanny visited her native city for the first time since her marriage, Henriette Herz was sixteen and newly married, Dorothea Mendelssohn a little younger and Rahel Levin a child of nine. Before the Berlin salon came into its prime, Fanny had already founded her own in Vienna.