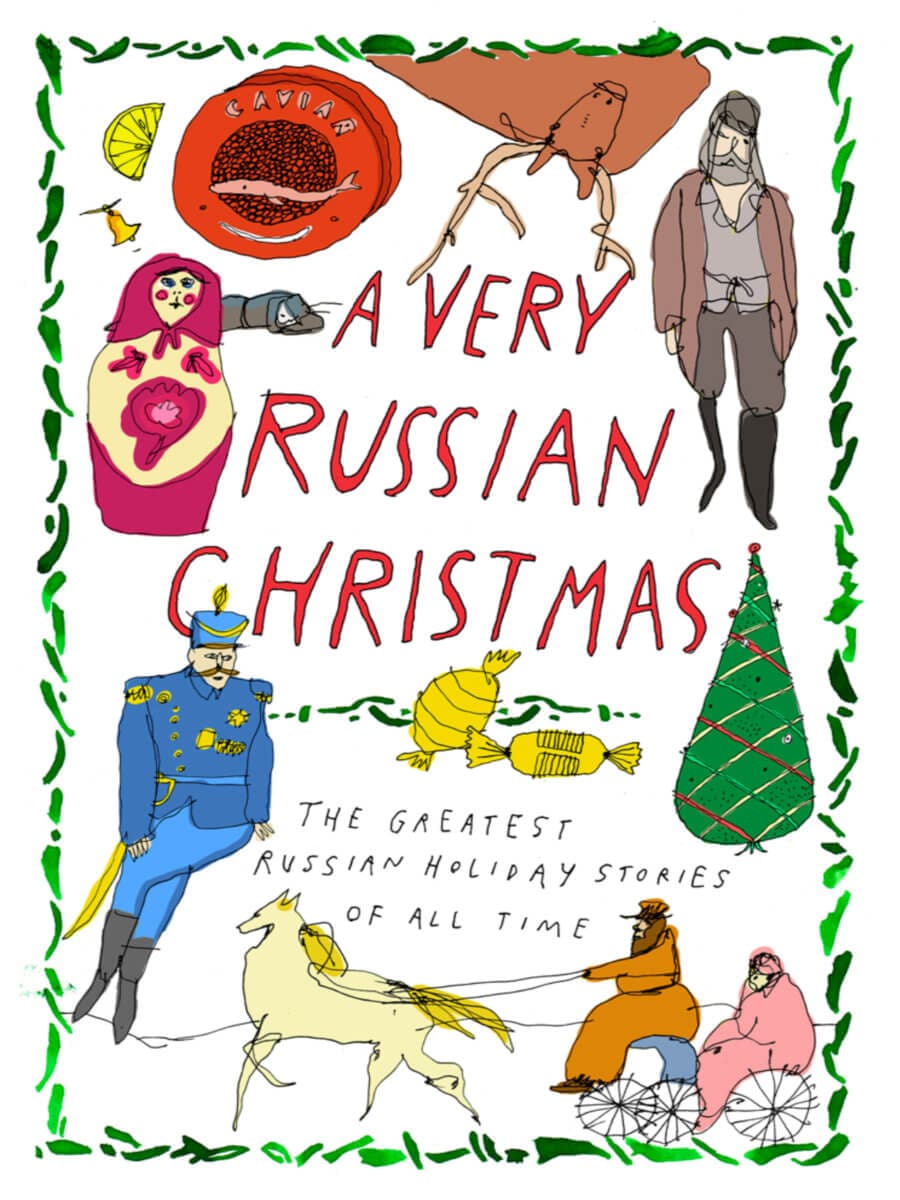

Crimson ribbons and troubled souls, landowners yearning for love, burning cheeks, salmon, and caviar. This is Russian Christmas celebrated in supreme pleasure and pain by the greatest of writers. Running the gamut from sweet and reverent to twisted and uproarious, and with many of the stories appearing in English for the first time, this collection will satisfy every reader. Dostoevsky brings stories of poverty and tragedy, Tolstoy inspires with his fable-like tales, Chekhov’s unmatchable skills are on full display in a chronicle of a female factory owner and her wretched workers, Klaudia Lukashevitch delights with a sweet and surprising tale of a childhood in White Russia, and Mikhail Zoshchenko recounts madcap anecdotes of Christmas trees and Christmas thieves. There is no shortage of vodka or wit in this volume packed with sentimental songs, footmen, whirling winds, solitary nights, snow drifts, and hopeful children. With its wonderful variety and remarkable human touch, this collection proves that Nobody Does Christmas Like the Russians.

Please consider other volumes in this series: One for Each Night, A Very Mexican Christmas, A Very French Christmas, A Very German Christmas, A Very Italian Christmas, A Very Irish Christmas, A Very Indian Christmas, and A Very Scandinavian Christmas.

Excerpt from A Very Russian Christmas

Mikhail Zoshchenko

From “My Last Christmas”

It’s been a long time since I’ve celebrated Christmas.

The last time was about seven years ago.

Before Christmas itself I took a trip to some relatives in Petrograd. Luck wasn’t on my side: I ended up having to spend the night at some rinky-dink station. The train was running twelve hours behind.

And the station really was rinky-dink. There wasn’t even a buffet.

The security guard, by the way, was bragging: “In general, there’s a buffet but nowsabout,” on account of the holiday, it was closed. It was small comfort.

There were about twelve of us hapless travellers at this station. There was a fish merchant with a beard, two students, and some woman in an old-fashioned cloak, with two suitcases, and the others were folks unfamiliar to me.

Everybody sat submissively at the table in the tiny waiting hall and only the merchant showed signs of anger raging inside. He jumped up from the table, ran to the guard, and we could hear him squeal and puff himself up. One of the managers answered him calmly:

“There’s no way of knowing … Eight in the morning … No earlier.”

Among the passengers there was somebody else: a tidy-looking wee old man in a fur coat and a tall fur hat. At first the old man, laughing good-heartedly, comforted the passengers, gently looking in their eyes, then he took up singing in a quiet, reedy tenor: “Thy Birth, O Christ, Our Lord.”

He was a wee old man with an absolutely pious appearance.

Good nature and meekness were visible in each of his movements.

He sat on a chair and, swaying in time, was singing “Thy Birth.” But suddenly he popped up off the chair and disappeared from the station … A few minutes later he returned, holding in his hands a spruce twig.

“Here!” said the wee old man in exaltation, as we walked up to the table. “Here, dear ladies and gentlemen—behold we have a tree!”

And the wee old man proceeded to stick the tree in a decanter, humming softly, “Thy Birth, O Christ, Our Lord”

“Here, ladies and gentlemen,” the old man said again, taking a few steps away from the table and admiring his handiwork, “On this festive day, because of somebody’s sin, it is we who must sit here like the wretched of the earth …”

The passengers looked at the fussy figure of the little old man with displeasure and irritation.

“Yes,” the old man continued, “because of somebody’s sins … Of course, on this festive day, we—Orthodox Christians—are used to spending it amidst our friends and acquaintances. We are used to watching our little children jump in indescribable delight around the Christmas tree … Out of human weakness, fine ladies and gentlemen, we enjoy gobbling up ham with green peas and sausages one after another, and a slice of goose, and a tipple tipple of the you know what …”

“Tfu!” said the fishmonger, looking at the wee old man with disgust.

The passengers slid forward on their chairs.

“Yes, gentlefolk,” the old man continued in the most delicate of tones, “we’re used to spending this day in delight. However, even if that’s not the case, you don’t rail against God … They say, not far from here there’s a small

church, I’m going there … I’m going, fine gentlefolk, I’ll cry my share of tears and light one of the wee candles …”

“Listen,” said the merchant, “maybe we can get ahold of something? Perhaps we can get our hands on some, eh, some of that ham? Perhaps if you ask around?”

“I suspect it’s possible,” said the wee old man, “for money, dear ones, anything is possible. If we can get it together …”

The merchant extracted his wallet, banged it on the table, and began to count. The passengers happily turned in their seats, pulling out their bills.

In a few minutes, after counting the money they’d collected, the wee old man announced delightedly that there was enough for food and drink and more on top of that.

“Just don’t be long,” said the monger.

“I’ll light a wee candle,” said the old man, “cry a tear, ask the Orthodox Christians where I can make a purchase, and be back … For whom among you, gentlefolk, shall I light a candle?”

“Light one for me,” said the woman in the cloak, rummaging in her wallet and pulling out bills.

“No, Madame,” said he, “allow me, with my most modest means, to do you a Christian deed. Who else among you?”

“In that case, for me,” said the merchant, hiding his wallet.

The wee old man nodded his head and left. We could hear his voice: “Thy Birth, O Christ, Our Lord”

“What a saintly little old man,” said the merchant.

“A surprising little old man,” somebody seconded. And the passengers began to discuss the wee old man.

An hour went by. Then two. Then the clock struck five. The old man hadn’t come. At seven o’clock in the morning he still wasn’t there.

…