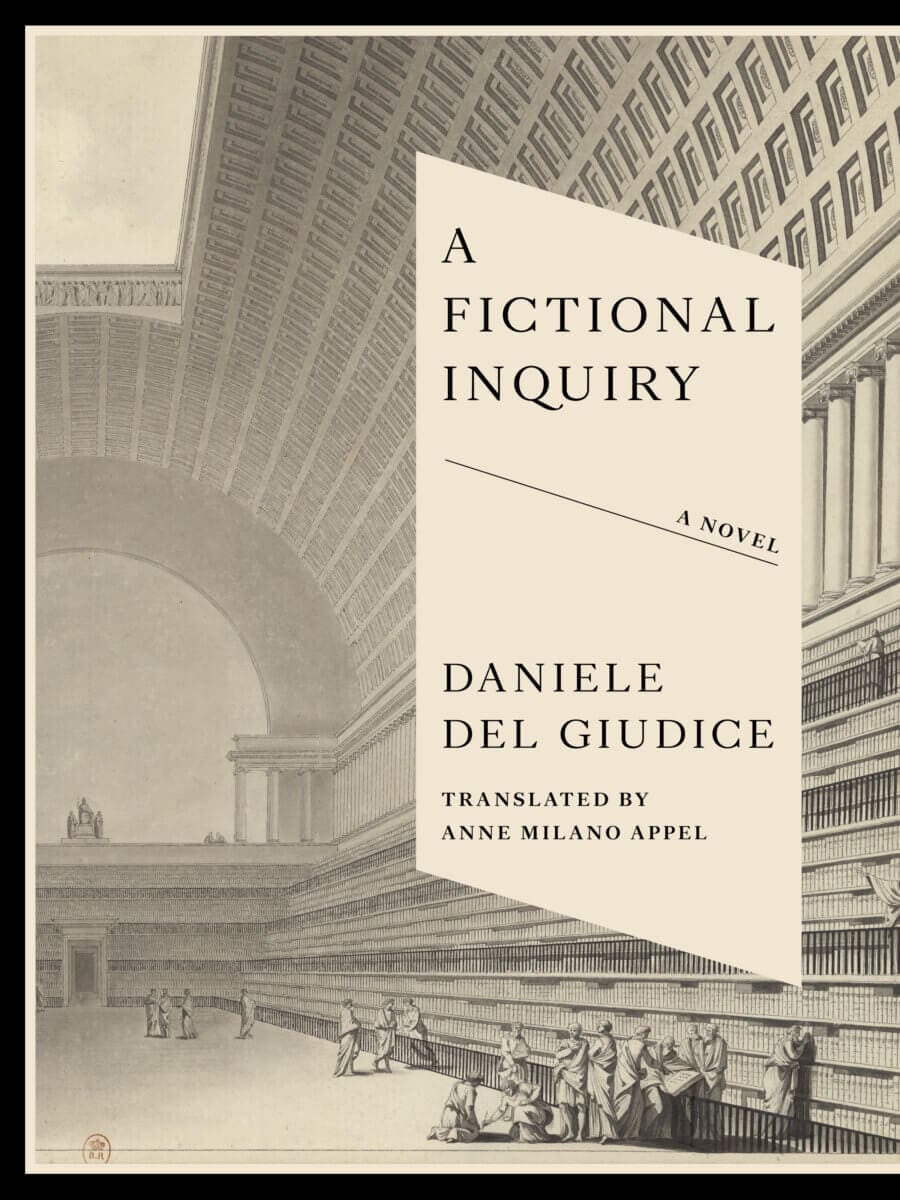

This haunting novel was championed by Italian author Italo Calvino who called it a “very simple book, straightforward to read, but at the same time possessing great depth and extraordinary quality.” First published in 1983 and never before translated into English, A Fictional Inquiry tells of an unnamed narrator visiting Trieste and London to retrace the footsteps of a fabled literary figure. The narrator is intrigued by the elusive, long dead man of letters whose career proved decisive to the culture of his native Italy despite his apparently never having written a line. There are encounters with those who once loved him, walks along the streets he frequented, and visits to his favored cafés, bookstores, and a library in search of an answer. Why did he leave no written trace? In the end, as Calvino wrote when this book originally appeared in Italian, who the legendary author manqué actually was is beside the point. What really matters are the questions and the disquiet running through these luminous pages, the dialectic between literature and life playing out just below the surface. A Fictional Inquiry—which includes notes from both Calvino and translator Anne Milano Appel—is a gem of unparalleled writing appearing in English for the first time.

Excerpt from A Fictional Inquiry

In the train, three things, probably related, though in a way I can’t make out. First of all, the child moving his little plastic train up and down against the window glass, maybe thereby experiencing the childish completeness of being inside something while still being in possession of it from the outside. He’s quite focused as he plays, but the toy train may compensate for the loss of an external form that is no longer visible. He plays with it spontaneously, in the most perfect way, as is the case with a toy train in a train.

Then the fact that the child and his mother and I are in a car of the old intercity train that was designed as a little sitting room, with three or four armchairs and a pale wood counter that must have been a bar and is now absolutely empty. The most beautiful trains are those with a few carriages that have the feel of a house; the furniture is actually moving, like the train itself, so everything is moving and traveling, but the body’s posture does not follow along, it’s not a travel posture, it’s relaxed, in a sprawling position, as if it were at home.

Finally, when we enter the narrow stretch between the rocks and the sea, on the way out of the city, a blinding ray of light strikes the window and, for an instant, traces the outlines of things on the ground. I look out at the monumental white lighthouse: You can imagine the trajectory of that flashing beam making its way to eyes out at sea, where it would be recognized by its recurring intervals, by the type and color of the light. The mariner follows the lighthouse by repeatedly calculating the distance; it’s a good way, I think, to approach things, constantly measuring how far away they are.

Dazed, the child also looks at the lighthouse, and I see his eye in profile, a transparent little ball with a flat iris, a sheet of colored construction paper at the base of a glass bubble. It always makes me shudder a little to see that even in the eyes there is absolutely nothing. Which is why I close mine and fall asleep.