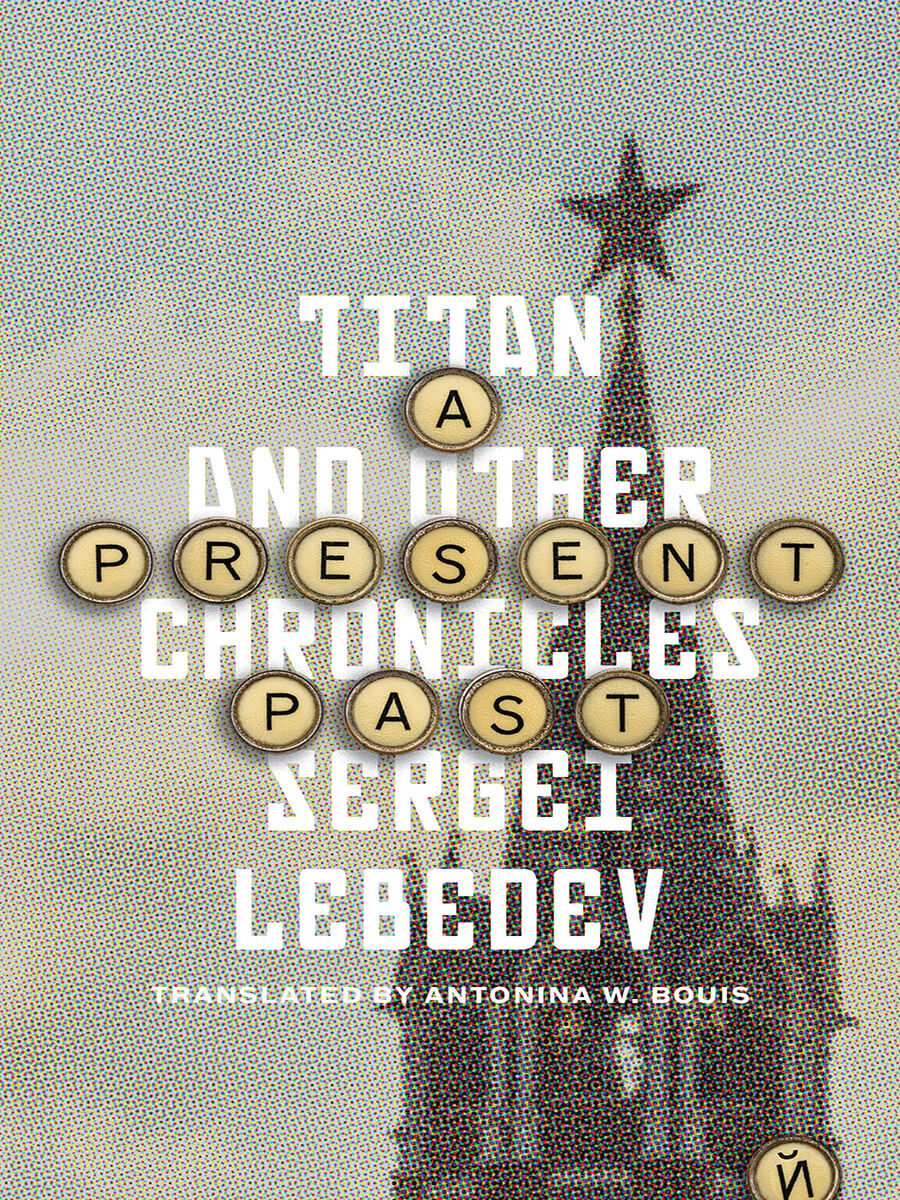

The Soviet and post-Soviet world, with its untold multitude of crimes, is a natural breeding ground for ghost stories. No one writes them more movingly than Russian author Sergei Lebedev, who in this stunning volume probes a collective guilty conscience marked by otherworldliness and the denial of misdeeds. These eleven tales share a mystical topography in which the legacy of totalitarian regimes is ever-present—from Katyn to Chechnya, from Lithuanian KGB documents to the streetscape of unified Berlin, from the fragments of family history to the echoes of foot soldiers in Russia’s wars of aggression. In these stories, as in Lebedev’s acclaimed novels, the voices of things, places, animals, and people seek justice for a restless past, where steel claws scrape just beneath the surface and where the heredity of evil is uninterrupted, unacknowledged, unnamed.

Excerpt from A Present Past

Preface

I remember the final years of the Soviet empire.

Even though I was a child, I remember the phenomenon of mystical feelings, elemental and ubiquitous, as sudden as a volcanic eruption.

The sense of the approaching end of an era also elicits mysticism. However, the Soviet Union was an atheist state, built on the doctrine of materialism. Soviet ideology—at least on paper—called for a rational view of the world and the only ghost allowed was the “specter of Communism” that Marx and Engels had prophesied in the nineteenth century.

That made it all the more astonishing how quickly the other world appeared, the “reverse” side of Soviet consciousness; a dark storeroom filled with everything that had been tossed, hidden, crossed out of life and memory during the seventy years of communist rule.

A new mystical folklore arose before our eyes, seemingly out of the air of the epoch.

It spoke of evil places, anomalous zones where the laws of physics did not hold.

About strange creatures, poltergeists who lived in houses and apartments and persecuted residents they did not like, with knocks and noises and moving objects.

About children born with characteristic birthmarks on their bodies if their ancestors had been executed by firearms.

People’s minds sought images, sought a language to describe the tragedy, and they turned to mystical allusions to make the evil past real and at the same time managed to become estranged from it, turning it into the subject of another world and another reality.

Well, ghosts are not born by themselves. They are born of a silent conscience. Dual moral optics. They are as real as the ignored knowledge of crimes and the refusal to accept real responsibility.

They are the distorted voice of the dead turned into mystical images. The voice of unwanted witnesses.

Throughout its existence, the Soviet state destroyed people and destroyed any memory of the destruction.

However, the archives of state security still retained millions of files. Millions of invented accusations. Millions of false interrogations built on a single artistic scenario: from denial to confession of nonexistent guilt.

These cases, this metatext with its standardized subjects and genres, may in fact comprise the most important and terrible Russian work of the twentieth century. The evidence of evil which remains unread.