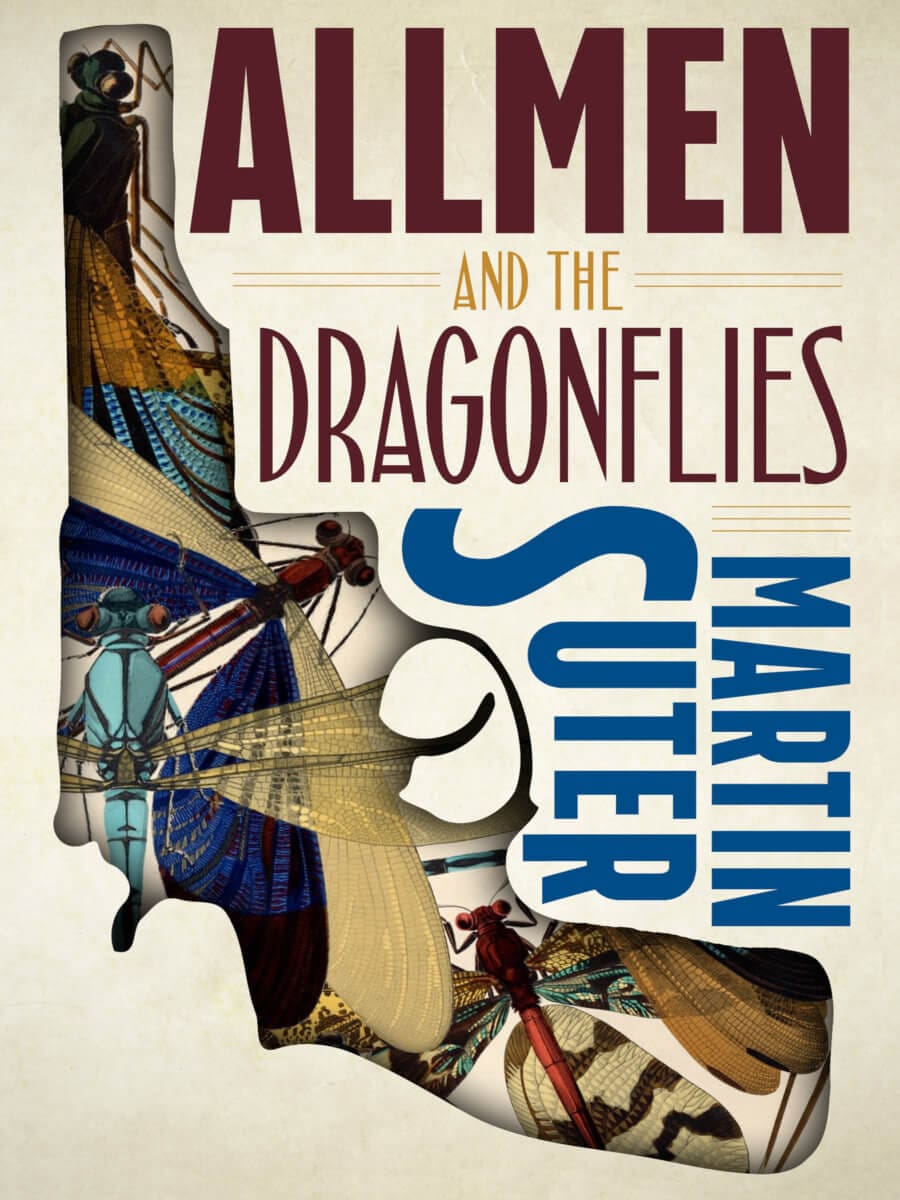

A thrilling art heist escapade infused with European high culture and luxury that doesn’t shy away from the darker side of human nature.

Johann Friedrich von Allmen, a bon vivant of dandified refinement, has exhausted his family fortune by living in Old World grandeur despite present-day financial constraints. Forced to downscale, Allmen inhabits the garden house of his former Zurich estate, attended by his Guatemalan butler, Carlos. When not reading novels by Balzac and Somerset Maugham, he plays jazz on a Bechstein baby grand. Allmen’s fortunes take a sharp turn when he meets a stunning blonde whose lakeside villa contains five Art Nouveau bowls created by renowned French artist Émile Gallé and decorated with a dragonfly motif. Allmen, pressured to pay off mounting debts, absconds with the priceless bowls and embarks on a high-risk, potentially violent bid to cash them in. This is the first of a series of humorous, fast-paced detective novels devoted to a memorable gentleman thief who, with his trusted sidekick Carlos, creates an investigative firm to recover missing precious objects.

Martin Suter’s novel The Last Weynfeldt was published by New Vessel Press in 2016.

Excerpt from Allmen and the Dragonflies

Allmen habitually rested for half an hour in the afternoon. This little siesta didn’t just refresh him, it also reminded him every day that he was privileged to be a man of independent means. Even after all these years, sleeping while the rest of the country was pursuing productive activity gave him a sense of enormous happiness he knew only from cutting class at school. He called it “cutting life.”

There was nothing more delicious than closing the curtains on whatever was going on outside, slipping under the cool quilt in your underwear and listening to the distant sounds of the world with half-closed eyes. Only to emerge from your afternoon snooze shortly afterward, amazed and invigorated.

His bedroom was filled by a king-size bed, a bookshelf for his nighttime reading matter and two closets for the section of his wardrobe appropriate to the time of year. The rest of his clothes were also stored in the laundry.

He lay in bed, next to him a paperback for the unlikely situation he was unable to doze off. The rain pattered softly against the window, otherwise the world outside kept quiet.

He couldn’t entirely banish Dörig’s letter from his consciousness. Not because of the twelve thousand, four hundred and fifty five francs. He would find them somehow. It was the nature of this final demand which was disturbing him.

However badly Allmen managed money, he was extremely good at managing debt. He had learned that during his time at Charterhouse, the exclusive boarding school in Surrey where his father had sent him at fourteen at his own request. Allmen wanted to be cleansed of his family’s jumped-up farmyard whiff, as he put it.

At Charterhouse handling debt was an unofficial part of the boys’ education. Debt was nothing to be ashamed of. On the contrary, it was good for one’s reputation to have some. For pedagogic reasons the school rules set a limit on the amount of pocket money pupils could be given. This led to a proliferation of money lending. Everyone boasted about their debts, looked up to those with the highest, deferred them or serviced them in installments, always paying them off with style and nonchalance.

Allmen had continued this in later life. Right from the start, the income from his inheritance had failed to match his growing need for capital, and his deceased father’s trustees soon lost their patience. They were succeeded by a series of handpicked advisors, whose advice contributed more to Allmen’s expenses than his income. He soon found himself forced to finance his lifestyle and his new acquisitions—alongside the Villa Schwarzacker these included apartments in Paris, London, New York, Rome and Barcelona—by parting with some of the more secure, solid assets his father had bequeathed him. And when he had used up that supply, he maintained himself via sales—mostly rash—of his new acquisitions, first the real estate, then furniture, then collector’s items, then one by one the decreasing number of items which in his former life he had considered indispensible. And finally items acquired in a similar manner to the Kangxi vase.

As a rich man, Allmen had been a highly generous creditor. And now in his role as debtor, he expected the same patience and understanding from his creditors. Initially he was not disappointed. His former solvency stood him in good stead. What he had were not debts; they were outstanding payments, accounts, pending items. Creditor and debtor treated each other with the respect everyone owes someone they are dependent on.

And this was why Dörig’s letter had opened up a new dimension. It was a crude, vulgar fit of rage from a man prepared to use violence, a category he had not yet encountered. Allmen abhorred all forms of violence. Including the verbal form.

He was seriously perturbed. But when he woke half an hour later from his siesta, amazed and refreshed as ever, this perturbation had receded into something quiet and distant.