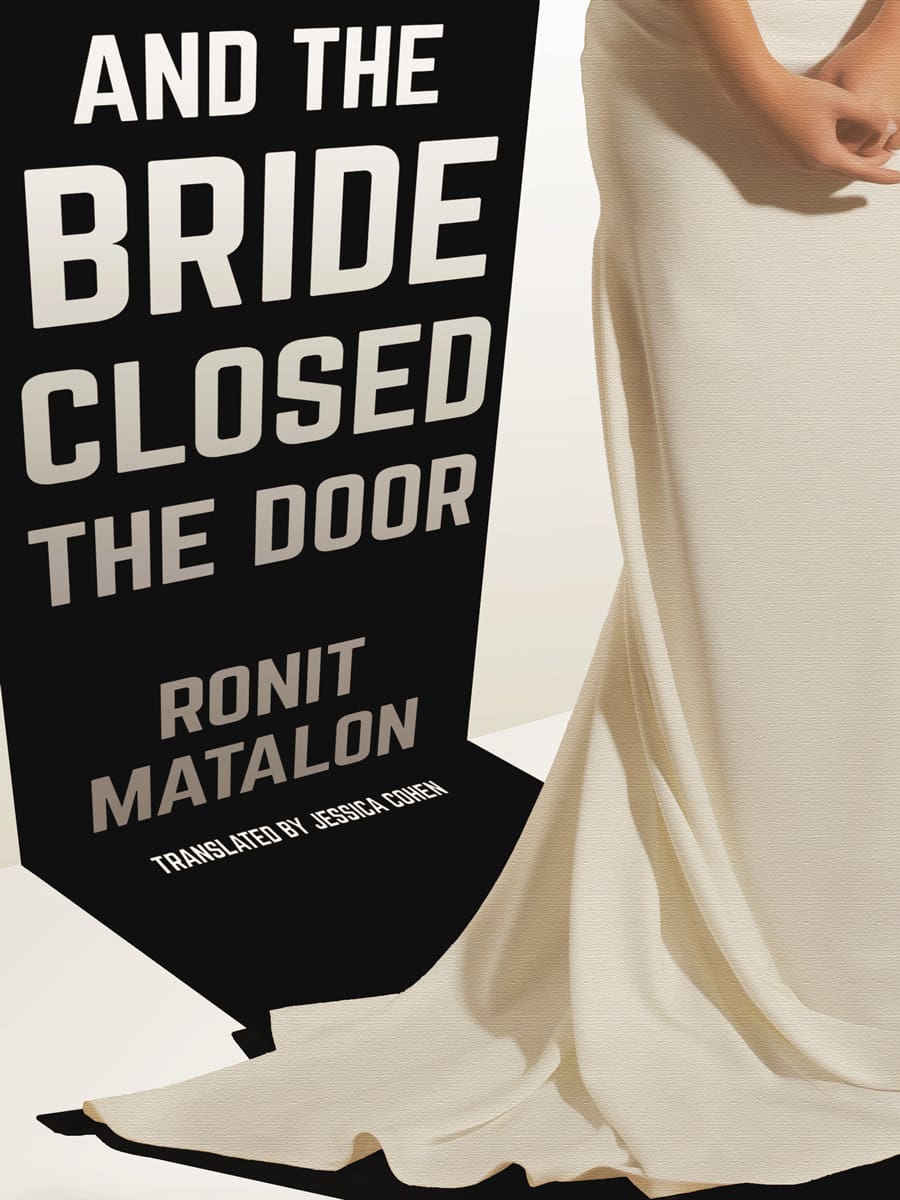

A young bride shuts herself up in a bedroom on her wedding day, refusing to get married. In this moving and humorous look at contemporary Israel and the chaotic ups and downs of love everywhere, her family gathers outside the locked door, not knowing what to do. The bride’s mother has lost a younger daughter in unclear circumstances. Her grandmother is hard of hearing, yet seems to understand her better than anyone. A male cousin who likes to wear women’s clothes and jewelry clings to his grandmother like a little boy. The family tries an array of unusual tactics to ensure the wedding goes ahead, including calling in a psychologist specializing in brides who change their mind and a ladder truck from the Palestinian Authority electrical company. The only communication they receive from behind the door are scribbled notes, one of them a cryptic poem about a prodigal daughter returning home. The harder they try to reach the defiant woman, the more the despairing groom is convinced that her refusal should be respected. But what, exactly, ought to be respected? Is this merely a case of cold feet? A feminist statement? Or a mourning ritual for a lost sister? This provocative and highly entertaining novel lingers long after its final page.

Excerpt from And the Bride Closed the Door

The young bride, who had been locked in her room in utter silence for more than five hours, finally made her announcement, then repeated the astonishing declaration three times from behind the closed door, through which four pairs of ears listened anxiously and with the utmost devotion. “Not getting married. Not getting married. Not getting married,” she recited in a flat, almost bored voice that sounded extremely distant and nebulous, like the final vapors of a scented cleaning spray.

Three of them were crowded into the sad hallway (the grandmother had been placed upon a wicker stool opposite the door when her feet had grown weary from the long wait) and avoided looking at one another for a long time, as though any eye contact might turn the declaration they had just heard into a solid fact, confirming not only its content, but worse—its significance. And so they simply continued to stare at the shut door with its old-fashioned dark wood veneer, seemingly anticipating a thawing, a softening, a miraculous melting—if not of the bride then at least of the door—and hoping for something further: a continuation of the sentence, an idea or a word that might emerge through the door like the wet head of a newborn closely followed by the body itself sliding out.

“I’m cold,” said the bride’s mother, Nadia. She tried to encircle her fleshy shoulders with her own arms, which were encased in the tight-fitting, prickly lace sleeves of the light gray evening gown she had been trying on, at the hairstylist’s request, though her feet were absentmindedly clad in plaid winter slippers with zippers down the front. Her dyed blond quiff perked up in surprise over her forehead, and similar wonderment veiled her gaze when it unintentionally fell on the grandmother, her own elderly mother, by whose presence she seemed as perplexed as she might be by an unfamiliar piece of furniture that she had not ordered yet was suddenly delivered to her home.

“What did Margie say?” the grandmother asked cheerfully. She was hard of hearing and generally “not with us,” as Nadia put it, and throughout all these hours of waiting she had sustained a dazzling smile, full of the pearly white teeth inlayed by the dentist only a week earlier, in honor of the wedding. “What did she say?” she repeated, hanging her round gaze on the chrome door handle, which was positioned precisely at her eye level. She sat on the stool with her legs obediently straight and close together, like a kindergartener at circle time, and patted the remaining two apple quarters (two she had already eaten) on a dish towel on her lap.

Nadia leaned over and gripped her elbow: “Go on, go rest in the living room for now. We’ll let you know when there’s any news.”

The grandmother munched on some apple, and a thin dribble of pale yellow juice ran from the corner of her mouth down to her chin. “Booze? What booze? They’ll have plenty of drinks at the catering hall, don’t worry,” she assured them, wiping her fingertips on the dish towel.

The phone rang in Matti’s pocket. He quickly silenced it, but a few seconds later it rang again and he turned it off yet again. “It’s not her?” asked Nadia. “It’s not her,” the groom replied, “I have her phone, did you forget?” Nadia closed her heavily made-up eyes. “I didn’t forget. I didn’t know you had it. How could I forget something I didn’t know?” She paused. “What are we going to do?” Then she repeated her question more quietly, as if trying not to wake someone: “What are we going to do?”

Matti looked at her intently, somewhat wistful yet completely alert, and seemed to be considering her question, although he wasn’t really. She could feel his gaze jabbing her in the spot right between her painted eyebrows with an injection of despair, tense expectation, and something else she couldn’t quite name. Startled, she turned sharply to Ilan, her nephew, who was leaning over on her right and whispering in her ear. “What? What did you say?” Nadia was confused.

“I corrected you. I said: ‘God, what are we going to do?’ That’s what I said you should have said. ‘God, what are we going to do?’” Ilan displayed his ugliest sneer, intentionally exaggerated, then went back to covetously playing with Nadia’s six gold bracelets. He rolled them up and down her arm, counted them over and over again, pulled them almost up to her elbow then dropped them back down, one by one, to her wrist.

“What does God have to do with it?” Nadia pulled her arm away impatiently. “Why would you bring God into this?”

“It’s true. God forgets no one. Allah ma biyinsash khad, like they say,” the grandmother announced with contemplative satisfaction, rocking slightly from side to side on the stool to stretch her buttocks. Nadia put her hands over her eyes. “I can’t take her. I can’t. Explain to her what’s happening,” she murmured at Ilan without looking at him, and leaned her back against the wall.

Ilan wiped his dry hands on his pants, moved closer to the grandmother’s stool, knelt down before her with his eyes straight across from hers, cupped her milky cheeks in his hands and held her head right in front of his own, so that she could watch his lips move. “Gramsy!” he said quietly, in a soft but persuasive voice. “Lena!” The grandmother’s face lit up and her wide nostrils trembled slightly with joy, as though her name pronounced by Ilan were a surprising discovery. “Can you hear me, sweetie?” he asked with a grave look. She nodded vigorously. “It’s Margie. Mar-gie. She’s not getting married in the end,” he explained. “Why not?” the grandmother asked, as a look of confusion and dread spread over her face. “Why isn’t she getting married?” Ilan replied slowly, accentuating every syllable: “She doesn’t want to. She said she doesn’t want to get married.” “Ever?” the grandmother inquired. “She doesn’t ever want to get married?” Ilan reached out, stroked her hair, and tucked a long strand behind her ear. “I don’t know if not ever, sweetie. We don’t know. For now—she doesn’t want to get married.”