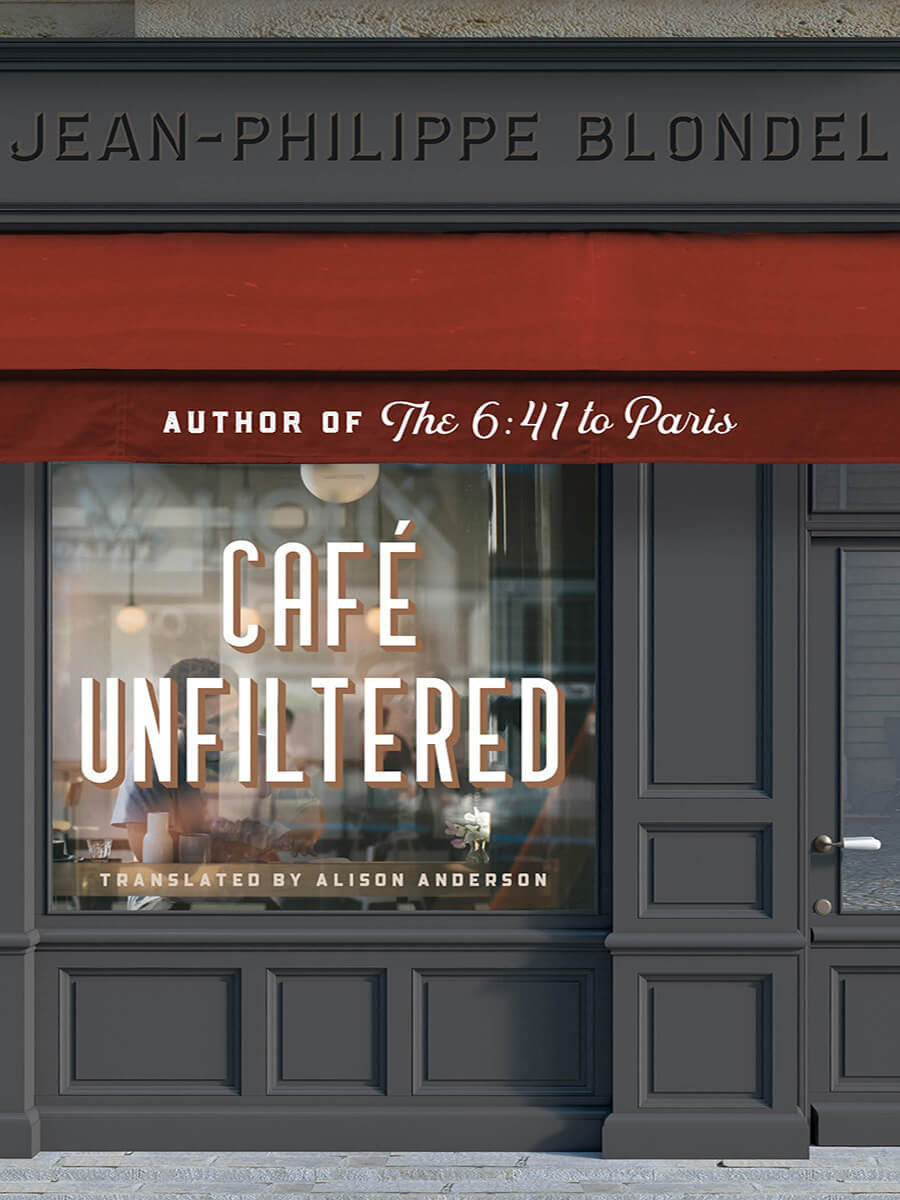

At a classic café in the French provinces, anonymity, chance encounters, and traumatic pasts collide against the muted background of global instability. Jean-Philippe Blondel, author of the bestselling The 6:41 to Paris, presents a moving fresco of intertwined destinies portrayed with humor, insight, and tenderness. In the span of twenty-four hours, a medley of characters retrace the fading patterns of their lives after a long disruption from Covid. A mother and son realize their vast differences, a man takes tea with a childhood friend he had once covertly fallen for, and a woman crosses paths with the ex who abandoned her in Australia. Amidst it all, the café swirls like a kaleidoscope, bringing together customers, waiters, and owners past and present. Within its walls and on its terrace, they examine the threads of their existence, laying bare their inner selves, their failed dreams, and their hopes for the uncertain future that awaits us all.

Excerpt from Café Unfiltered

I’m a parasite.

That’s precisely what José the waiter must think of me. He slaps his napkin over his shoulder and lets out an exasperated sigh, but he hasn’t threatened to throw me out yet. Honestly, that would be ridiculous: in all the time I’ve been seeking refuge here, the room has never been more than half full.

Customers may have started coming back inside, but they’re uneasy. They keep their mask within reach, and finger it nervously. The limit imposed on gatherings has been lifted, and if we want, we can get together in groups of twelve or fifteen. What’s worrying is this new variant everyone’s talking about, with a Greek letter for a name, but it makes you think of India all the same—majestic elephants, Bollywood, and overcrowded cities.

The terrace, on the other hand, is often packed with people. They’ve heard that there’s virtually no risk out in the fresh air, that droplets are dispersed on the wind and won’t contaminate our skin. Droplets, too, have been let out of confinement, have become immaterial. Still, people remain discreet when it comes to laughter and exclamations. And at the end of the tunnel. People squinting. Groping for the daylight. All these curfews have accustomed us to behaving like pet mice. At night we scurry around at home, without sticking our nose outside.

It’s the same when it comes to conversation. It’s often mezza voce, for fear of arousing the demons of Wuhan or elsewhere. We mutter the word “vacation” tentatively, and at the same time make a face that means: Like last year, our vacation won’t be anything like it used to be. Wait and see. All of us, wait and see.

Except me.

Sitting on my leatherette banquette, I’m not waiting for anything. I’m observing. The way men and women behave. The ones who used to greet each other with open arms, and now they touch each other’s shoulder or upper arm, sometimes daring to let a hand linger on the other’s skin, until they withdraw their fingers, furtively, and rack their brains wondering where they’ve left the hand sanitizer.

Now and again our gazes meet. They realize I’m staring at them and they move a few inches away. I’m making them uneasy. Then they spot my notebooks and pencils, and the big fountain pen, and they breathe more easily. An artist. The satisfaction of being able to pigeonhole me. Ah yes, the arts. Culture. Fields that have suffered more than others, over the last two years, right? So abruptly deprived of an audience and their only source of income. How are we going to make it through these times? It’s almost as if they’re about to give me a few euros, along with some words of compassion and encouragement. We are all with you. We believe in you.

I wonder how much they’ll remember, once they look away. The image that’s been printed on their retina. A woman in her thirties. Her hair on the short side. Straight. Brown, almost black. The color of her eyes? Green? Blue? Brown? No, honestly, now, they haven’t been paying attention. Nor to her figure—which must mean there’s nothing worthy of note where that’s concerned. Especially as she was sitting down, you see. It’s always tricky trying to gauge a person’s height when they’re not standing there in front of you. She had a nose piercing, didn’t she? Or maybe it’s just what you expect from an artist, it’s such a cliché, with artists. Oh yes, because she’s most definitely an artist. She was sketching. The streets nearby. The interior of the bar. Who knows, maybe when I first noticed her she was sketching my portrait. I’d really like to see that. If I run into her again, I’ll ask her. Except that if I do run into her, I won’t recognize her. In the meantime, she’d do better to find another occupation. A real job, in other words.

I think about all the places I’ve worked. The offices in Paris. The company with an open-plan layout in Helsinki. The tearoom in Vantaa. The convenience store next to my parents’ place. After all these years waiting on other people, going through their lives, all I want now is peace and quiet. To step aside. That’s it. That’s the right way to put it. Since the autumn, I’ve stepped aside. As I had already cut myself off from the rest of the world a few months earlier, when I came home from Vantaa, I’ve become marginal. No, that’s not right. I’m on the red line separating the margin from the rest of the page. It’s a rope I’ve stretched tight and I’m walking on it, clumsily. I don’t know when I’ll fall and whether it will all end badly. Above all, for the time being it doesn’t interest me.

It’s other people who captivate me. All the people my age, making their way, fearful or bold, convinced they’ve been through the most intense time in their life during these various lockdowns, and that they’re rediscovering a world that they’d taken for granted. I find them touching, and I envy them as well. Though you might not think it, I’d like to join in the dance again, too, but I’ve forgotten the steps.