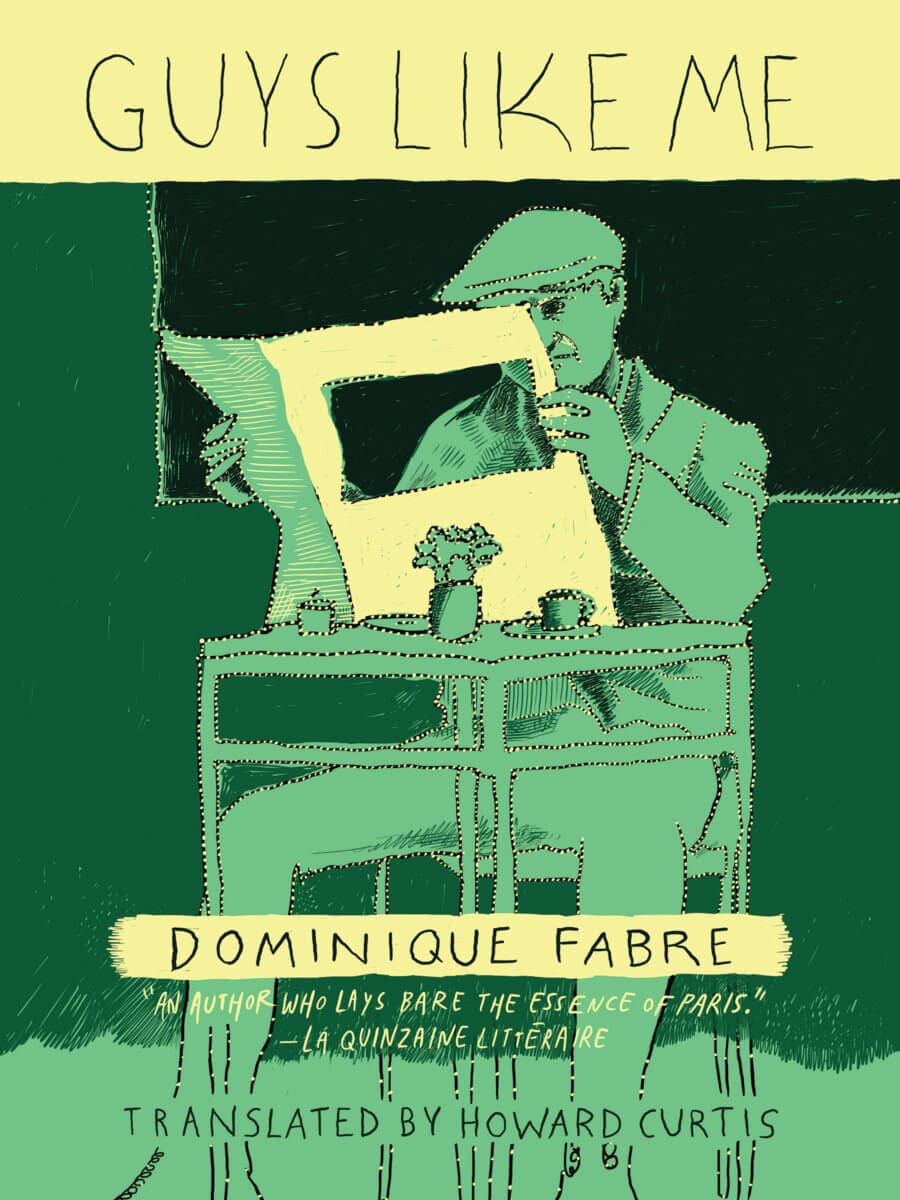

Dominique Fabre, born in Paris and a lifelong resident of the city, exposes the shadowy, anonymous lives of many who inhabit the French capital. In this quiet, subdued tale, a middle-aged office worker, divorced and alienated from his only son, meets up with two childhood friends who are similarly adrift, without passions or prospects. He’s looking for a second act to his mournful life, seeking the harbor of love and a true connection with his son. Set in palpably real Paris streets that feel miles away from the City of Light, Guys Like Me is a stirring novel of regret and absence, yet not without a glimmer of hope.

Excerpt from Guys Like Me

1

His eyes were blue, from where I was. He looked tired. He looked as if he’d been waiting there for a long time, although that was impossible. Neither of us could have known in advance which way we’d be going that day. I’m a mature man, I’m fifty-four, but in some respects I’ll never be mature enough. For example, the way I sometimes get scared when I meet someone. Mostly you just run into people, and it’s of no consequence. Actually, our lives are full of consequences placed end to end, and it’s hard to believe that the lack of consequences in this case could have lasted all those years. But he looked familiar, from where I was. From where I was, it might still have been possible, somehow, to turn around and walk away, even though obviously I would never have turned around and walked away of my own accord. But a car might have started, in which case I’d have had to get out of the way, or I might have looked the other way and not seen his reflection in a shop window. I’d have reacted by saying to myself what does that guy want with me? And I’d probably have ignored him, I’d probably have forgotten him. His face looked drawn, but his hair wasn’t gray. I’ve almost lost my hair. Sometimes I put my hand through it, and there’s nothing there. My ex-wife used to laugh when I did that, and I don’t think I took it well. I don’t like taking a wrong turn, but it’d be right to say that when we met again we’d both taken a wrong turn. Maybe our lives, too: lots of wrong turns placed end to end, you can never reconstruct the whole journey.

*

His clothes were almost as all-purpose as mine. He’d been wearing them longer than I had. His shoes were polished, in spite of the wear and tear. At that moment, he’d already resumed his place in my life, and I in his. But had we ever really been friends? He was carrying a computer case, and of course I could never have imagined how important it was in his life. It was a long time since he’d last had his own things, in his life, and he kept all those papers in his case, in an ashamed kind of way. He was pretending too. He’d always pretended, I told myself later, remembering things from long ago. But I wasn’t so sure of that in the days that followed. His eyes were blue, and he was carrying that fake case. By the time we were pushing thirty, his good times were already behind him, as far as I knew. He’d already had a beautiful wife, a beautiful apartment, and we’d stopped seeing each other except from time to time, although I often felt like calling him. I didn’t know why he was where he was. He didn’t tell me, he was long past explaining things. Try to find out what happened, and you never get the answers you want. Try to figure out how the Earth turns, how people live and die, notice the changes on the streets, and there’s too much missing, when you get down to it. How are you doing? Neither of us said things like that, things like, how many years has it been? What have you been doing with yourself all this time? He didn’t have time for things like that, with his case in his hand. He said only hey, I thought it was you.

“Me too. It is Jean, isn’t it?”

“Yes, don’t you recognize me?”

“Yes, yes, of course I do.”

We shook hands, didn’t say any more, just carried on walking together. We were in the area near the station, where I almost never go, not since I moved. But for some reason, I sometimes make a detour and go back there, stay there an hour, without talking to anyone.

*

He didn’t live in the neighborhood anymore either. There was a time when he hadn’t lived anywhere in particular, to be honest. A day here, three nights there, even sometimes in hotels that didn’t have names, only street numbers, surrounded by recent Eastern European immigrants and Arab regulars, he was a bit old for that. We walked back up the street, without intending to we were going in the same direction, the two of us. We sat down in a café on Rue d’Amsterdam, pretty much halfway along the street. A place where for a long time now, maybe forever, people have been crossing diagonally to gain a few seconds, on this side of the street, on the way to one of the side entrances to the station, near the big post office. It was because of his case that I realized. How could a guy like that get to this point? I’m not the only one to ask myself that question, not that he talked much about it. His hands also seemed as if they came from another time. It’s crazy, but that’s how it is. We were at the back of the café, where it was dimly lit. Above the bar were posters advertising special offers, the week’s happy-hour cocktails. That kind of thing shows me I’m also from another time really. I’ll never be able to manage. Every time that idea comes into my head, I get scared, I don’t know what to do to get rid of that feeling.Though sometimes, I like it. They didn’t have happy hours in the bars we used to go to together in the old days. There was a time when I often went to England for my work, and there too, I noticed it, time must have passed everywhere, often in the same way. In the light of the booth, his face looked drawn. He was carrying a shadow with him, along with all the rest, the lines, the deep marks left by our lives. Which of us was the first to ask what the other wanted to drink? I can’t remember. I’d really like to remember everything, I might be able to trace the crack he’d slipped through, the crack through which he left again, even if I couldn’t help him. I like helping people, though, in life. I’m not a good Samaritan, or a bad one, it’s the way I was born, period. How can I explain it?

*

He didn’t talk at first. He looked as if he needed rest. He also seemed to be contemplating something, a kind of map of his life, a whole bunch of forks in the road, our encounter being one path, or a kind of crossroads. I don’t know how to talk about these things. We don’t like to say these things. But we see them in the faces of the people we meet. The fact is, nothing about these things changes with time. For years, they’ve been giving tents to poor people so that they don’t die of cold during the night. But we weren’t in winter anymore, so why did I think of that when I saw him? He was clasping his case to his chest, sitting on the imitation leather banquette. He’d insisted on my taking the banquette, as if that was still one of the generous gifts he could afford. But I played a stupid game with him, without even being aware of it, and said I had to go take a leak. He nodded slowly, with a big, cracked smile, and finally took his place on the banquette. When I came back upstairs, I saw him sitting there with his case clasped tightly to his chest. A steel cannabis leaf in the colors of the Jamaican flag was hanging from the zipper, and later I saw a whole bunch of guys like him and me with cannabis leaves in the colors of the Jamaican flag, but not all of them were down on their luck. I feel like telling jokes, like with him. He was waiting for me to say something, as if he really wanted me to take responsibility for the stupidity of this reunion.

“Let me look at you.”

*

I said that, or maybe I didn’t, but from that first time, I could never look at him enough, a bit like when you’re in love, and you’d like to have a woman’s face and body permanently in front of your eyes, so as not to offend them. Of course I thought he’d changed a lot. Maybe we both simultaneously recalled dates and events, memories we could have shared. He didn’t open up in that café, didn’t relax his smile. But I recognized him when he jutted out his lower lip and blew upwards. That was something he always used to do when we were teenagers. Maybe that stupid gesture was something he thought was seductive, the way other people use their smiles.

“Do you ever hear from André?”

He stopped smiling. André was another guy with blue eyes and a smile. André Lebars? Yes, that’s the one. He made a face, no, he hadn’t heard from him lately. Why should he care about him anyway? That was kind of the impression he gave me at that moment. He didn’t want anyone standing between us, I sensed at that moment that he had decided to cadge money from me.

*

It started when I turned forty, like most guys I know. I sponsor a little orphan, a little Haitian boy as it happens, and every year I keep the letter he sends me, a completely stereotypical letter to the white man who sends him a check for twenty-five euros every month. A year after my divorce, I also started volunteering in a hospital, but that way of doing good didn’t suit me all that much, because often, the next day, I’d start to feel symptoms, and more than once I fell ill. How can you give a hand to someone who’s dying anyway?I never figured out the answer to that. There were support groups too, with shrinks, only it bored me, and I stopped, it wasn’t my thing. Then I met a woman I was hoping to get love from, but nothing like that happened. I was forty-four when I discovered that you can hope to get love in return for a washing machine, two installments on a car, and other things like that. When I realized that, I was cured of that woman, and of others too in the long run. I wasn’t seeing much of Benjamin at the time. Just after our separation, I tried to live close to him, I’d call him every two or three days, but even during the times when he needed me I often disturbed him. So I found myself calling him less often, he was growing up. I’m very proud of him, he’s done well so far. But I can’t say anything about that pride because I think all I’ve done is pay, since he was eleven, and he’s twenty-six now. I missed all that, I sometimes tell myself. He soon got into the habit of living with a sporadic father, his mother didn’t set him against me too much, I let things go during the divorce proceedings in order not to hurt them. Two years later was the time of the woman with the installments who needed a washing machine, a time also of unemployment and depression, and I couldn’t pay the alimony in time. A bailiff came at seven in the morning. I’ve never dared to ask Benjamin if his mother told him.