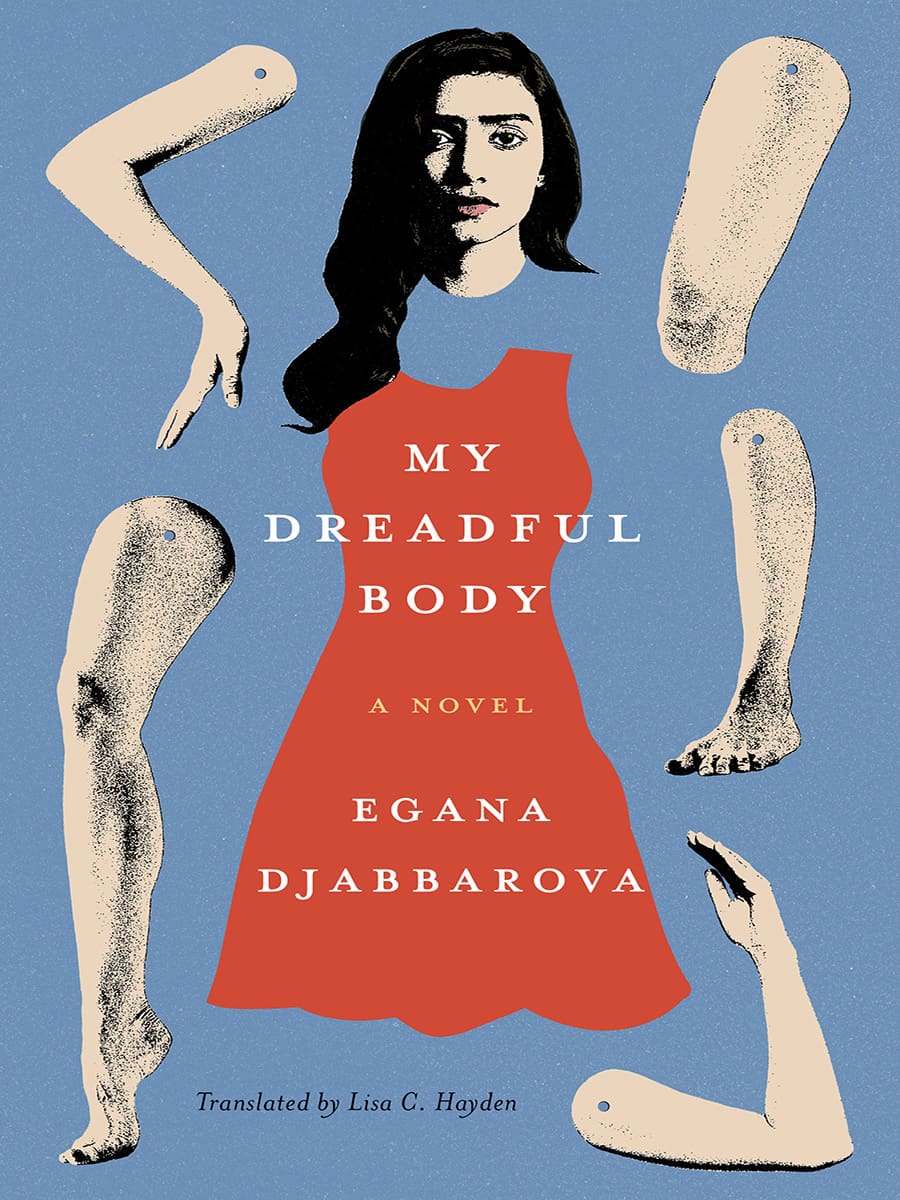

A dazzling debut novel about a young woman’s vexed coming of age in a traditional Azerbaijani community in Russia, grappling under the weight of Muslim patriarchal norms and a debilitating neurological condition. The mysterious affliction leaves her unable to control her muscles, plagued by pain and speech disorders, defying diagnosis. Addressing each body part with the scrupulousness of a medical researcher, the narrator explores memories, traditions, and taboos related to her physical self. In the process, a woman once destined for the role of a beautiful marriageable daughter comes to be perceived as damaged goods. With verbal elegance and poetic power, Egana Djabbarova unveils a hidden world in which illness unexpectedly facilitates her liberation. Her book stands in the proud tradition of confessional feminist writers like Sandra Cisneros, Arundhati Roy, Audre Lorde, Toni Morrison, and Jamaica Kincaid.

Excerpt from My Dreadful Body

According to my mother’s strict orders, the big, bushy black eyebrows in the oval mirror were not to be plucked. This was not just because Allah forbids his creatures from changing anything about their bodies. It was also because I was unmarried. The primary event in the life of any young Azerbaijani woman, after all, is undoubtedly her wedding and only that wedding can bestow the right to make changes, even if Allah does not approve of them. In small mountain settlements, the eyebrows were first and foremost in differentiating an innocent, unmarried young woman from a woman who had already married.

Eyebrows that were even, almost artificial, and so thin they might have been drawn with ink to let people around them know that a girl was now forever a woman, that thick brows resembling paradisiacal shrubbery were in her past. Yes, most of the girls in a typical Russian school who admired themselves in tiny little round mirrors from state-run newsstands were perfectly calm when they used soulless metal tweezers to pluck unruly, bristly little hairs. I pondered for a long time what possible danger there could be in tweezing my eyebrows, given that the girls in my class were all still the same the next day, maybe even a little happier. My brows seemed to expand daily, occupying more and more space between my eyelids. If my girlfriends had something like pale vines, then I had the huge dark wings of a mountain bird.

The question of how to deal with my eyebrows preoccupied me just as much when we went to visit my father’s relatives in Baku. Dense mattresses and coverlets of various colors, adorned with all kinds of decorations, lay, lazily stacked, on a bed in a small room. My aunts and grandmothers had filled most of those mattresses themselves. They first thoroughly washed lambswool, then carefully laid it out right in the yard, under the dazzling Baku sun, until the time came for the longest and most torturous part of assembly. Clean pillowcases decorated with roses were quickly filled with wool that Mama and Bibi, my aunt, packed in firmly, as if it were stuffing for a gutted turkey. They then sewed the edges by hand and pierced the center of the mattress with long stitches made by the very thickest and largest needles, which were so difficult and dangerous to use that they often covered the women’s hands in bloody constellations. It was on those lovingly sewn and stacked mattresses that I sat with my cousins, silently observing how grown women with glistening rings on their fingers used silk thread to pull out each other’s brows.

I recall wondering where their hands had mastered all those secret motions and how they’d learned to manipulate the thread so quickly and energetically that it flawlessly removed the unwanted while leaving the essential. The skin reddened quickly after recognizing the bitterness of loss, as if it mourned each tiny hair. Twenty minutes later, new brows had replaced the old, engraved on the skin like an ornament on a vase. Cold, calm, and unaware of their own past, those brows lent the face’s owner a new expression unique to those acquainted with the strength of one’s own willpower and the possibility of changing one’s body.