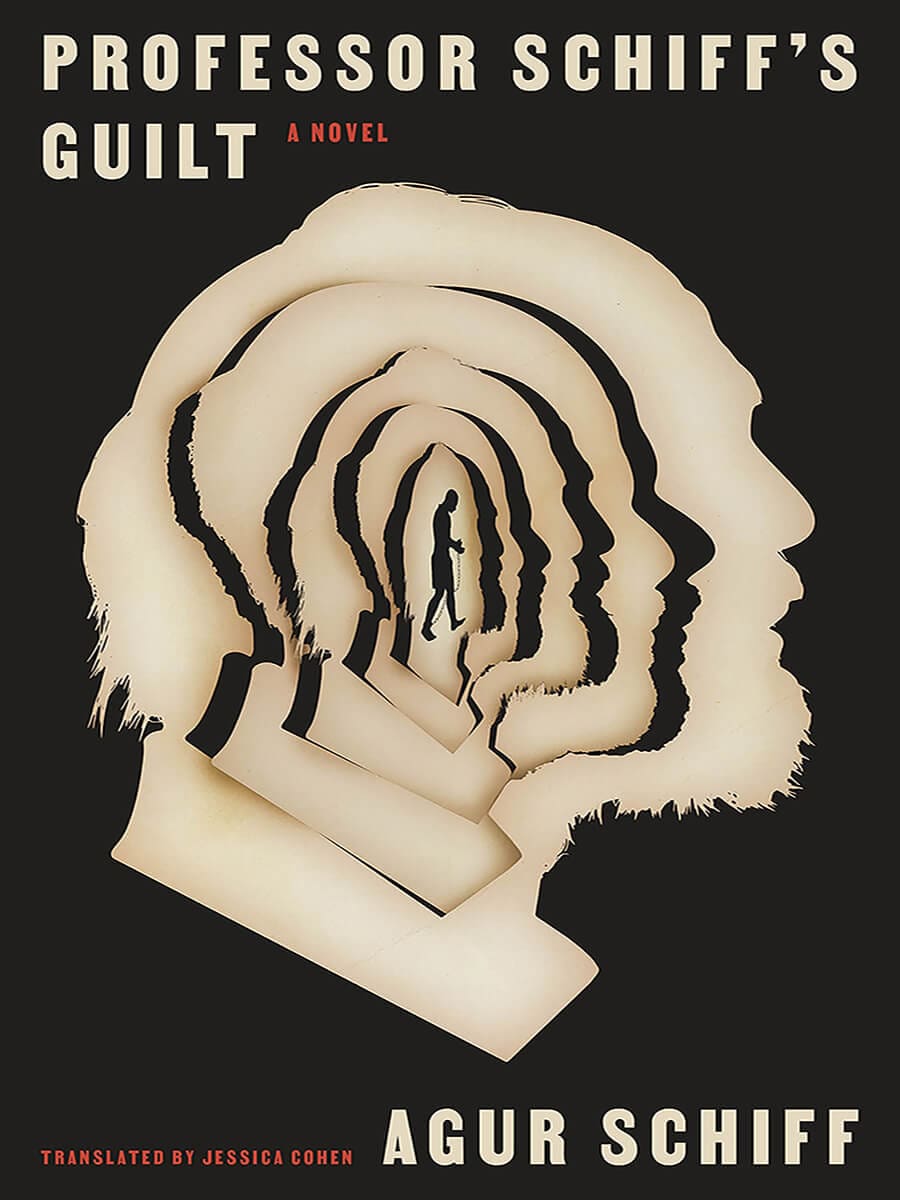

An Israeli professor travels to a fictitious West African nation to trace a slave-trading ancestor, only to be imprisoned under a new law barring successive generations from profiting off the proceeds of slavery. But before departing from Tel Aviv, the protagonist falls in love with Lucile, a mysterious African migrant worker who cleans his house. Entertaining and thought-provoking, this satire of contemporary attitudes toward racism and the legacy of colonialism examines economic inequality and the global refugee crisis, as well as the memory of transatlantic chattel slavery and the Holocaust. Is the professor’s passion for Africa merely a fashionable pose and the book he’s secretly writing about his experience there nothing but a modern version of the slave trade?

Excerpt from Professor Schiff’s Guilt

Yes, it’s true: my grandfather’s grandfather’s grandfather was a slave trader.

I cannot deny it. Nor do I see any point in obscuring this embarrassing fact. After all, I feel no affinity with the man, who departed this world almost a century and a half before I entered it. And I trust you will believe me when I say that our genetic linkage arouses more than a shred of discomfort in me.

Ladies and gentlemen, there are those who claim that the past always makes surprise appearances. Indeed, that is sometimes true. Except that what we have here is not a long-forgotten parking ticket that crops up out of nowhere and, if not paid—with interest, of course—might result in your bank account being seized. Nor are we dealing with an old woman who stops you on the street to remind you that she was the girl you were once madly in love with. No. The past I am being asked to submit to you, distinguished members of the Special Tribunal, is my family heritage, for good and for bad, and when it rears its head, I cannot pretend to be surprised.

Because I have known for years about my great-great-great-great-grandfather, Klonimus Zelig Schiff. About his business affairs, the fortune he amassed, and his mysterious disappearance. I have read about him. I have written about him. I have dreamed about him. I even know what he looked like.

In a portrait that hangs in the Surinaams Museum in Paramaribo, he stands upright and rigid, wearing a tricorn and a stern expression. He is flanked by his wife Esperanza, her head covered with a snood, and although she is not beautiful, she certainly is—how can I put this?—charismatic. In the background, a ship with billowing sails glides across a flat, gray sea that glistens like a sheet of zinc.

Naturally, almost instinctively, one seeks out the resemblance. It’s a bit like searching a baby’s face for the parents’ features. And when one persists, one always finds something. A certain glint in the eye. An angle. A contour. Generally speaking, though, ladies and gentlemen, perhaps you will agree that a face is an asset we tend to overvalue. Particularly if we take into account how quickly it withers and loses its capacity to do justice to its owner.

Then again, why should anyone care what the slave trader who was my great-great-great-great-grandfather looked like? As far as I’m concerned, you are entitled to think that Professor Schiff—namely, I—am him, as long as you can maintain your judicial objectivity. Not that I doubt your integrity, distinguished members of the tribunal. Not at all. I trust you unequivocally.