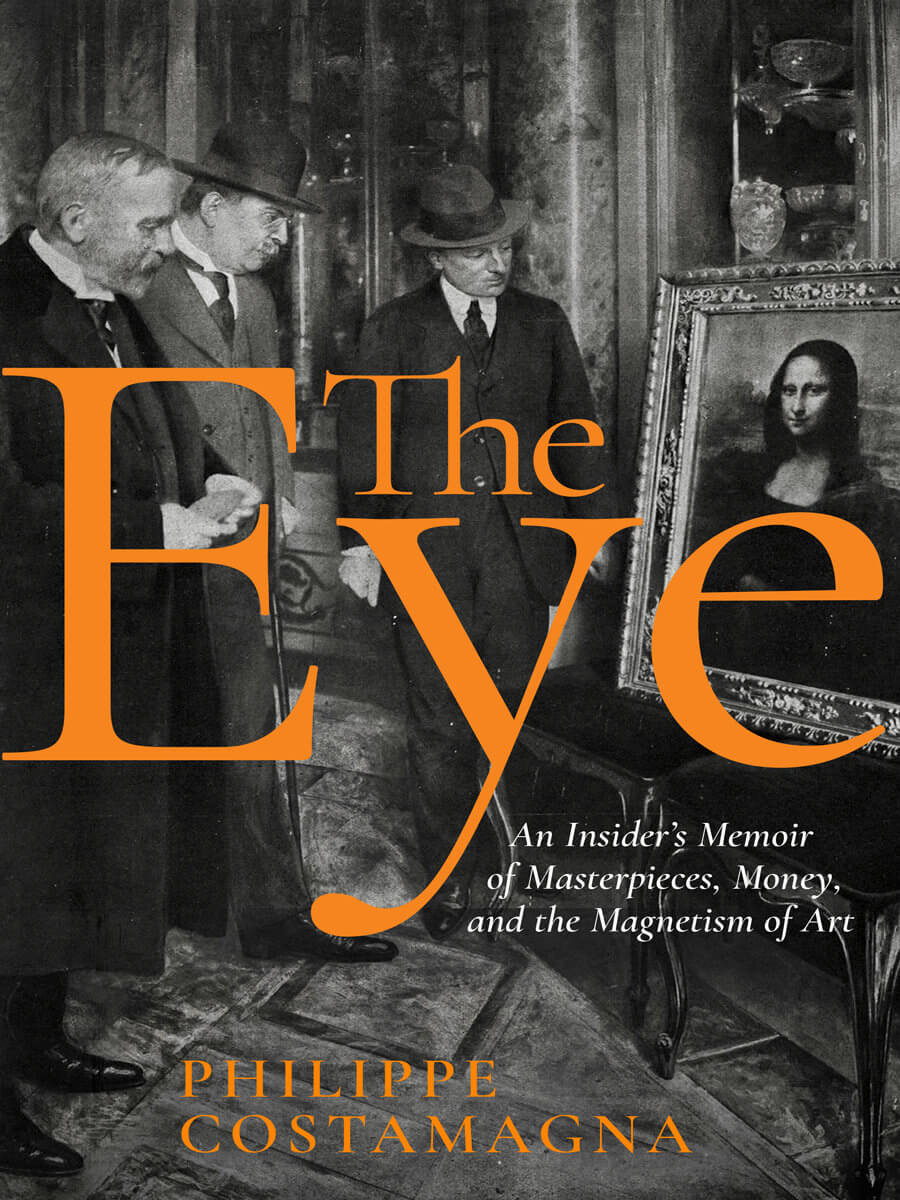

It’s a rare and secret profession, comprising a few dozen people around the world equipped with a mysterious mixture of knowledge and innate sensibility. Summoned to Swiss bank vaults, Fifth Avenue apartments, and Tokyo storerooms, they are entrusted by collectors, dealers, and museums to decide if a coveted picture is real or fake and to determine if it was painted by Leonardo da Vinci or Raphael. The Eye lifts the veil on the rarified world of connoisseurs devoted to the authentication and discovery of Old Master artworks. This is an art adventure story and a memoir all in one, written by a leading expert on the Renaissance whose métier is a high-stakes detective game involving massive amounts of money and frenetic activity in the service of the art market and scholarship alike. It’s also an eloquent argument for the enduring value of visual creativity, told with passion, brilliance, and surprising candor.

Excerpt from The Eye

We talk about a person having an eye for something. I would like to talk about the fascinating and little-known profession of being an “Eye.” The term might sound curious and surprising, but it would be impossible to explain in other terms what certain art historians do on a daily basis. If what we might call the “traditional” art historian—like the musicologist or the literary historian—is content to draw on a rich library and a vast image bank, the task of what I call the “Eye” is to establish the authorship of paintings by sight alone. His task is to see. To do so, it is crucial that he have direct contact with each work of art. Traditional art historians, musicologists, and literary historians construct complex hypotheses and conduct extensive research in order to expound their theories in books. The Eye, on the other hand, relies on dramatic coups de théâtre. His task, in short, consists of proposing a name. Every day, he is presented with unknown works of art. All too often, they are disappointing. But sometimes he is struck by something extraordinary, something as clear and irrefutable as it is unexpected.

He is an “Eye” in the same way that someone might be a “Nose” in the perfume industry. Noses identify scents and formulate perfumes. Eyes in the art world discover paintings and establish authorship at a glance. But there the comparison ends. If the great Noses are creators, artists sometimes capable of moments of genius, neither Eyes nor art historians generally can be considered to be creators. Eyes observe, and this observation triggers a process of memory that allows them to see. The process is not a form of genius but an acutely refined sense of analysis, an ability to break down the painting one is looking at into a collection of distinctive traits found in the diverse works of an artist.

It is this skill that enables the Eye to make discoveries. Unlike discoveries in mathematics, chemistry, or physics—those of Newton or Einstein for example, which are the product of the genius of an individual—the discoveries made by the Eye have more in common with that of Christopher Columbus. No genius was required. Merely a spirit of adventure and a happy accident, the result of a wager that he could find a new shipping route between Europe and India. The Eye is a miniature Christopher Columbus who roves the world of art, alert to any surprises. But whereas Christopher Columbus did not know what he had stumbled upon, the Eye on the other hand knows immediately. Like an explorer rediscovering Atlantis and knowing it can be nothing else. When an Eye is confronted with a work whose authorship he alone can identify, we say he has made a discovery. The more important the artist, the more important the discovery; and should the work in question be a masterpiece, executed by one of the greatest painters in history yet overlooked for centuries, we might even say a “great discovery.”

For an Eye, discoveries of this kind are very rare. He may search tenaciously for something, often without success, and then, without intending to, make unexpected discoveries. I confess that I have made at least one such discovery, completely by chance. It happened in October 2005, in the company of an Italian friend, Carlo Falciani, a specialist in sixteenth-century Italian painting like myself. We had been invited to Provence by an art collector in order to consider a painting that, though interesting, did not turn out to be the work we had hoped, and as so often is the case, the collector was left disappointed; in return, however, we made a discovery that would prove crucial to the history of art.

The previous day, we had visited the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Nice, where Carlo’s wife, also an art historian, wanted to study a number of paintings. The Villa Kotchoubey, which houses the museum, is one of the last vestiges of the Côte d’Azur whose dying echoes and fading light are captured in Tender is the Night by F. Scott Fitzgerald, the Côte d’Azur where the cream of European society came to sojourn before the Great War. At the moment when, all around, apartment blocks began to replace the sprawling grounds of the great nineteenth-century mansions, the city bought this villa from a Russian aristocratic family and transformed it into a museum. Here and there between the facades, it is possible to glimpse a sliver of the blue Mediterranean. Not far from the international airport, perched high in the hills of the city, it is one of the last remnants of the Belle Époque. The ground floor comprises a great hall with a gleaming granite floor bounded by marble columns and flanked by a monumental staircase and a covered courtyard.

Heading toward the great staterooms, one first passes through a long gallery whose walls are lined with fin-de-siècle paintings in keeping with the ambiance of the villa. Society portraits and oriental scenes, including The Harem Servant Girl by Paul-Désiré Trouillebert, plunge the visitor into the atmosphere of the period. At the far end of the gallery, the room is lit by a vast window. The sun, a frequent visitor to the bay of Nice, was high in the sky that morning, its rays piercing the panes at a steep angle. I remember we were chatting about this and that as we cast an inattentive glance over the collection, perhaps about the painting we planned to see the following day, when our eyes were drawn to a painting of Christ that hung at the far end of the hallway, a beam of sunlight falling upon the feet, glistening on nails that had a porcelain texture that to me was unmistakable. “Do you see what I see?” asked Carlo. Conversation gave way to a stunned silence. We were seeing the same thing. A providential ray of sunlight had revealed Bronzino’s Christ on the Cross, painted by the artist for the Panciatichi family in Florence circa 1540, a work long since lost and vainly sought by connoisseurs of Florentine art of the period.

It is quite a large painting. At five feet tall and three feet wide, it resembles an altarpiece. It depicts Christ crucified in perfect pallor and realism. The right leg, into whose foot a nail is embedded, is turned slightly inward. The prominent cheekbones, the hollow cheeks, the deep bags under the eyes are testament to a long ordeal. Even the slightest detail of the musculature is visible. The pastel pink loincloth intended to hide the Christ’s nakedness, with its realistic folds, has fallen slightly to reveal narrow hips in which it is possible to make out the bones. Beneath the head, tilted slightly to the right, the reddish-blond hair spills in tight, perfectly defined curls onto shoulders of alabaster. The painter has gone so far as to indicate, with light brush strokes, the grain in the wood of the cross.

As our eyes moved up the body, led by the distinctive rendering of the toenails, and without exchanging a word, we could both hear the echoing words of his first biographer, Giorgio Vasari, an artist himself and contemporary of Bronzino: “For Bartolomeo Panciatichi, he painted a picture of the Crucifixion, which is executed with great study and care, insomuch that it is clearly evident that he copied it from a real dead body fixed on a cross.” The scene is framed against an alcove of gray stone, the pietra serena, or “serene stone,” typical of the material used in the construction of religious buildings and important civil monuments in Florence. A thin trickle of blood runs from the feet down the wood and soaks into the stone niche.

It was an indescribable moment.