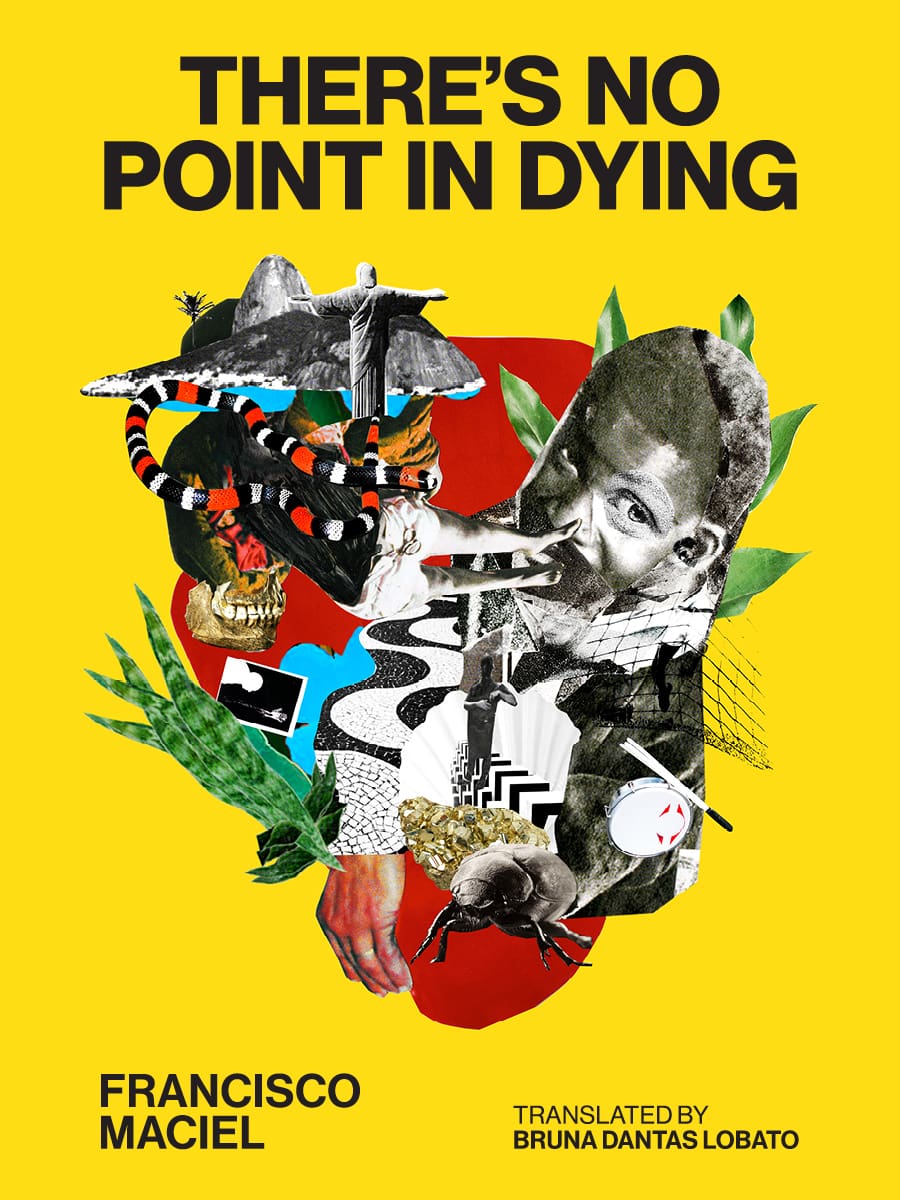

In this kaleidoscopic novel set in a favela of Rio de Janeiro—“in the city of stray bullets, in the land of lost opportunities”—a gang member runs wildly through the streets not knowing he has only seven minutes left to live. Barflies, prostitutes, immigrants, a gay couple, a taxi driver, cops, a mobster, and more populate Francisco Maciel’s first book to appear in English. Leaping back and forth across time and spiraling into the surreal, the novel coalesces around a brutal massacre. Maciel’s multiracial characters write poetry and discourse on soccer, insects, samba, and climate change. Gritty, unpredictable, and percussive, There’s No Point in Dying is translated by National Book Award winner Bruna Dantas Lobato.

Excerpt from There’s No Point in Dying

Dafé is running down Maia de Lacerda, it’s 2:15 in the afternoon, and at 2:22 he’s going to die. Tall, green eyes, coiled hair bleached bright yellow, he could’ve been whatever he wanted in life. Soccer player. Security guard. Gigolo. Star. He was meant to shine, he’d always thought. He was different, he was better. Then he made the wrong choices. Now he’s running down Maia. Just a pipe dream.

He feels like he’s soaring, but he isn’t. He spent the last two days fucking and nuzzling. No sleep, not enough food, too much to drink. He’s running on the sidewalk, on the left side of the street, past the parked cars, the trees, the lampposts. He’s trying to get to São Roberto. He’ll be safe then, he thinks. That’s where the woman he’s been banging lives, and though he told her they’re done, that’s where he’s headed, sex is no help in a situation like this, only gets in the way. But that’s where he’s going. His mother Mirtes’s would be safer, but he doesn’t think of that.

It’d be faster if he went through the Bezerra de Menezes Spiritist Center, jumped over the back wall to São Carlos and ran down the steps to get to São Roberto. But he keeps running down the street.

Everyone here’s a lame horse. That’s what Guile Xangô says, and Guile Xangô is a nice guy, weird and smart, he’s got a job, an address, identity documents. All the others are screw-ups, starving, one foot in jail. At least that part is true: it’s hard to find someone here who’s never done time. People pretend they haven’t. But when they’re hammered and high on blow they brag about it. They’re out and got nothing to show for it. No job, respect, dignity. They get wasted in seedy bars and snort white lines off black tables, the thin threads of their stupid lives going between their teeth. Life was better on the inside, they say. Then why not just stay there? Out here they got no rights, no respect. They’re nobody. They’re sick. They walked through the cell door right into a solid wall. They don’t exist. They don’t even know how much they don’t exist. Everyone here’s a lame horse, Guile Xangô says, and you know what you do to a lame horse? You put a bullet in it, kill it.

Dafé is still running down Maia, still feeling like he’s soaring. If he ran into the Halley Hotel, ran up the stairs, locked himself up in a room, Pernambuco would help him, he wouldn’t stand for cowardice, he’d be on his side. Dafé could stand a chance.

No one here has IDs. They work underground. They have marks on their skin instead. And he, Dafé, doesn’t have any of those either. He’s never liked tattoos. He’s proud of his own skin, clear, unblemished. He’s never fallen off his bike or his motorcycle. He’s never fallen.

The truth is that everyone’s gotten their marks right here in the present world. Guile Xangô has a historical explanation for this stuff. He says that all marks are inherited, like astral maps handed down from a past life. You believe this shit? It doesn’t make sense. Guile Xangô loves to talk about how slaves got punished. Like at the whipping post. Everyone’s feet swollen, all of today’s twists and turns from the thrashings at that same post in their past lives. All the slaves back then were marked like cattle. They were cattle. The body parts that would get marked: thighs, arms, stomach, shoulders, chest, faces. The marks could be a cross, a bell, flowers, letters (BP, FC, N&B). That’s what Guile Xangô keeps saying. Everyone here gets to be a slave again.

If you think about it (and you always think about it after talking to Guile Xangô) a lot of girls have these burn marks. Usually from boiling water. Mothers throwing hot water at their babies when they wouldn’t stop crying. A child reaching for the stove and pulling down the kettle, a waterfall on her face. Another kid throwing water at a girl walking home up the hill after school, so she’d learn her lesson and never look at another woman’s man. The ones with chemical burns from jealous cuckolded boyfriends like to show it off the most. They still wear tiny shorts, no matter that there’s only a scar left and the faint idea that at some time they were desired.