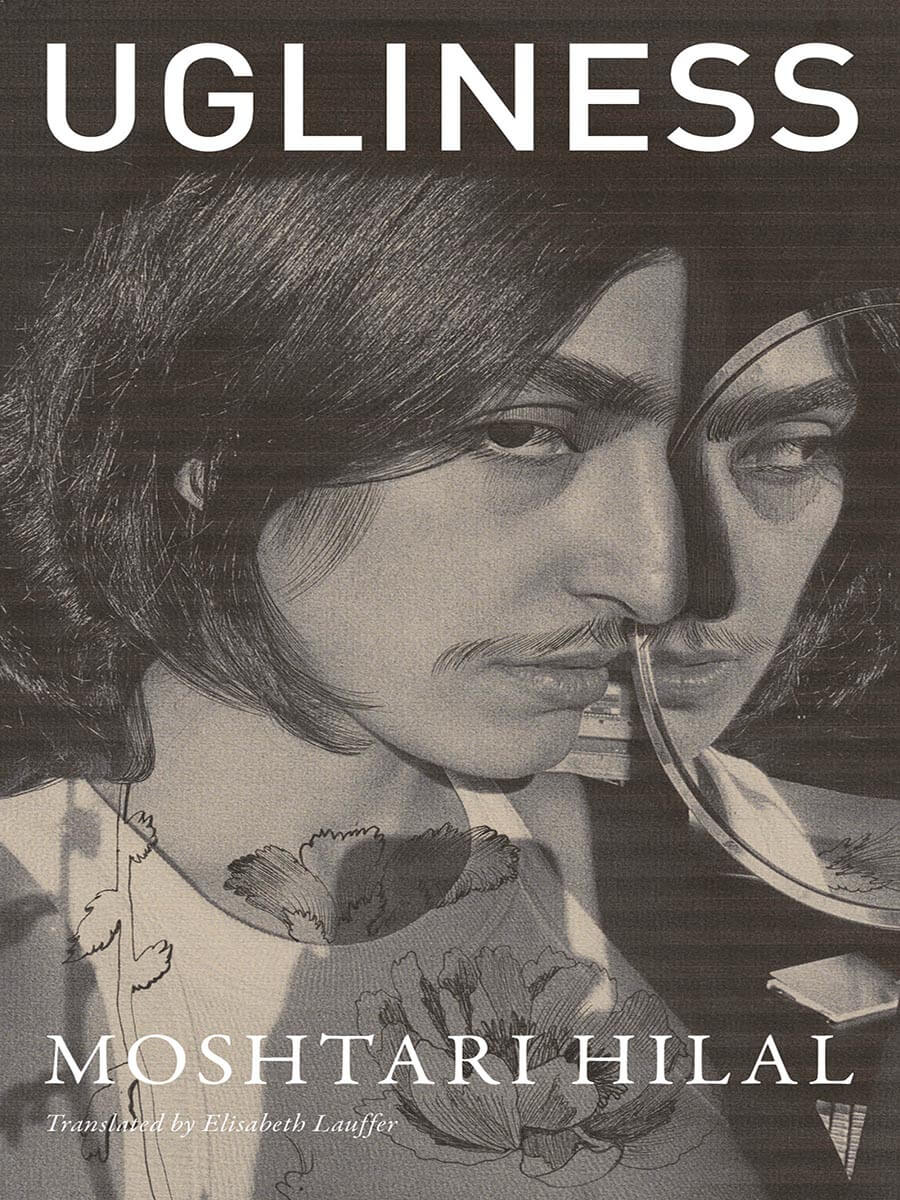

How do power and beauty join forces to determine who is considered ugly? What role does that ugliness play in fomenting hatred? Moshtari Hilal, an Afghan-born author and artist who lives in Germany, has written a touching, intimate, and highly political book. Dense body hair, crooked teeth, and big noses: Hilal uses a broad cultural lens to question norms of appearance—ostensibly her own, but in fact everyone’s. She writes about beauty salons in Kabul as a backdrop to the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan, Darwin’s theory of evolution, Kim Kardashian, and a utopian place in the shadow of her nose. With a profound mix of essay, poetry, her own drawings, and cultural and social history of the body, Hilal explores notions of repulsion and attraction, taking the reader into the most personal of realms to put self-image to the test. Why are we afraid of ugliness?

Click here to watch a videotaped conversation about UGLINESS between Moshtari Hilal and New York Times columnist Rhonda Garelick.

Excerpt from Ugliness

The cartography of my ugliness was a cynical drawing, a depiction I worked on day and night during the era of my pubescent body. I surveyed myself and added lines to the drawing that had not been there a day earlier. I looked in the mirror and erased and drew over the previous lines, which appeared more pronounced and grotesque with each passing day. I divided my small body into enemy territories. Chemical bleaches were applicable from the hips up, the razor from the hips down.

There was my head, big and unsteady on a twiggy neck and short little body. The face was such a mess, it had barely any room. I gave myself a pointed, cool nose, like a sharp blade, a place where anyone who got too close would cut themselves.

My eyes were glazed and tired, the eyeballs big and intense, the bags under them deep and exhausted. And my mouth became very small and insignificant, parched and alone.

That was the drawing—a cynical reckoning with my body, at once mathematical and militaristic. An honest analysis intended to prepare me for myself. There was no way I would ever be beautiful.

But would I allow myself to be exceptionally ugly? It was one thing to be short, thin, and distinctive, but to be short, thin, distinctive, and hairy—that went beyond excruciating. My battle plan took aim at that last element.

My fur became the scapegoat.

My mustache was striking and, unlike most other parts of my body, could not be concealed. When I spoke, each word was framed by little hairs. And these little hairs deprived me of my femininity. My mustache was thicker and coarser than the fuzz on my chin and cheeks. I could have bleached it to make it less noticeable, but then I would have had to do my whole face. How else could I have explained the transition from blond fuzz to the black hairs that sprouted from every follicle on my brow and the rest of my body?