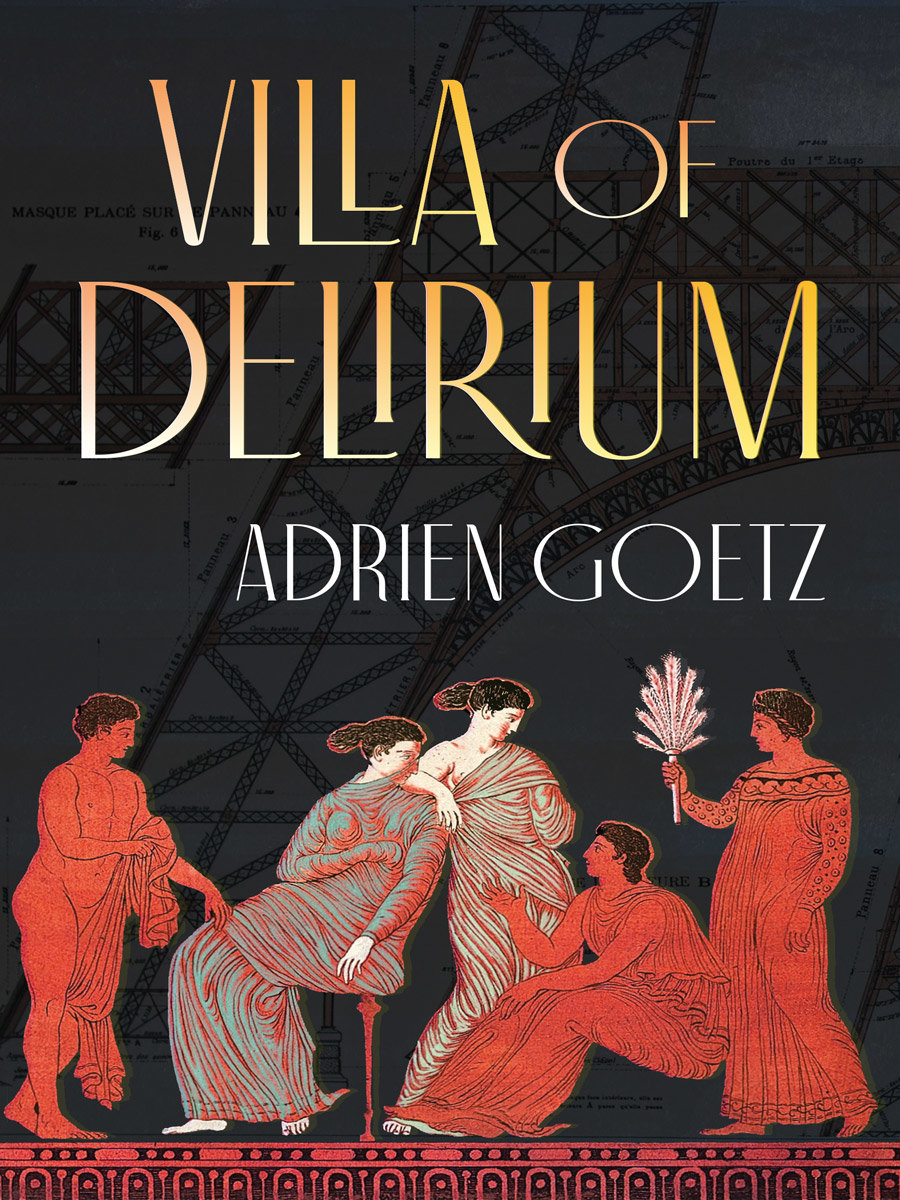

Along the French Riviera in the early 1900s, an illustrious family in thrall to classical antiquity builds a fabulous villa—a replica of a Greek palace, complete with marble columns and frescoes depicting mythological gods. The Reinachs—related to other wealthy Jews like the Rothschilds and the Ephrussis—attempt to recreate a “pure beauty” lost in the 20th century. The narrator of this brilliant novel calls the imposing house an act of delirium, “proof that one could travel back in time, just like resetting a clock, and resist the outside world.” The story of the villa and its glamorous inhabitants is recounted by the son of a servant from the nearby estate of Gustave Eiffel, designer of the Paris tower, and the two structures present contrasting responses to modernity. The son is adopted by the Reinachs, initiated into the era of Socrates and instructed in classical Greek. He joins a family pilgrimage to Athens, falls in love with a married woman, and survives the Nazi confiscation of the house and deportation to death camps of Reinach grandchildren. This is a Greek epic for the modern era.

Villa of Delirium is featured in a special report in The New York Times.

Download the Reading Group Guide for Villa of Delirium.

Excerpt from Villa of Delirium

As they watched the walls beginning to go up, the residents of Beaulieu began talking about “Chateau Reinach,” what the Reinachs called “the villa,” “the house,” or simply “Kerylos.” In the small seaside town, the project of building a home in the style of the ancient Greeks was discussed by the dairywoman in erudite tones and by the postman with a vague air that suggested that he had seen it all before. Monsieur Theodore Reinach, “a highly distinguished Parisian” according to the notary, had chosen the finest architect, who had actually worked on ruins in Greece. Another mystery—an architect who had learned his trade “on ruins.”

A few people in town knew that Emmanuel Pontremoli was the grandson of the rabbi of Nice. The locals eyed him in his panama hat as he took his seat in the cafe and unfolded his plans. He had slender fingers, a drooping mustache, and always wore a light-colored jacket. When he spoke it was clear that he was an architect: he constructed his sentences so carefully his interlocutors were tempted to repeat them verbatim, even as they realized they had completely forgotten what he had said. His tired eyes twinkled whenever he saw a pretty or well-dressed woman walk by. The notary, a dreary old fellow with round spectacles, who strung together clichés with the same attention he bestowed on certifying property deeds, knew nothing about that. The Reinach family had “an enormous fortune,” was “highly influential,” and everything was being done with the most “opulent extravagance.” The chateau would outclass all the mansions in the region that vied to be the most “playfully inventive,” the Moorish villas, the Palaces of Versailles in pink marble that made them look like powder rooms, and the Gothic castles concealing beach cabins in their turrets. Everyone bet that Art Nouveau style would triumph, it was going to be a “folly” that was just a little more outlandish than the others, like the Villa Gentil with its minaret—Monsieur Gentil was an art dealer—La Vigie, with its circular design—he was a friend of Gambetta and Waldeck-Rousseau who commissioned it—Chateau Saint Jean, the whim of an Italian-German banker—or the Villa du Parc, as big as the prince’s palace in Monaco—whose owner, Monsieur Peretmere, used to be a Freemason. On the promenade it was all anyone was talking about, they had seen this Reinach fellow, rather unfortunate looking, but it was his wife they really wanted to meet, dripping in emeralds, apparently, and his two brothers; everyone said they were absolutely inseparable.

Against this starling chatter, the arrival of the first slabs of marble provoked much excited commentary. Gleaming white, they reflected the sun onto the faces of the curious onlookers. Several months later, during the second phase, the colored slabs arrived, for the dining room, and some tiger marble for the thermal baths—thermal baths! The arrival at the railway station of the enormous polished columns met with applause. They came by boat, then took the little train, like everybody else, and were taken down to the site in drays that nearly collapsed under their great weight. Pontremoli had chosen a quarry in Carrara that was unchanged since Michelangelo, from which was dug the purest stone. Those who had been imagining a multi-colored house were a little disappointed. The dairywoman was quite sure of it: Greek temples were painted red, blue and yellow, the statues in garish hues. She would take out her Illustrated Almanac, which she had had for years, stored in the lean-to behind the dairy, and show its engravings of Greek temples to anyone who betrayed the slightest interest. She had her own little library, its books covered with butter paper. That was how she was so knowledgeable about everything. She even looked a little like a librarian, orderly, methodical, with that hint of melancholy mixed with resentment born of a fate that had her cataloguing milk churns when she ought to have been dealing in first editions.

Since no one was allowed onto the Reinach site, and the workers were so well paid that they didn’t sit around gossiping in cafes, nobody knew exactly what was being built. People imagined silver bathtubs and salons overflowing with indecent statues, and more naked bottoms than in a museum. Ancient Greek bottoms, according to the postman, are always “ambiguous.” He preferred Fragonard and Boucher, or Watteau’s The Embarkation for Cythera, which was a great deal more suitable. A Greek villa would offer an extraordinary spectacle, an abundance of pediments and staircases, and the priest, forgetting Christian charity, said at once: “What marvelous ruins it will make after those people are ruined.” Ruins: the word kept being uttered. Hearing the words “Greek villa” it was impossible to imagine anything else. You could already see the signs: “Warning—rockfall.” It was an excellent opportunity for the naysayers, who mocked that it was going to be a pasteboard pastiche of the Temple in Nîmes, a hastily daubed theater set, or a picturesque curiosity with broken columns and collapsing arches, like a cemetery or a meringue, or it was going to look like a gigantic clock without a dome, facing out to sea. Without shutters the salt would destroy everything. As the house went up it was supported on a wave of rumors that ebbed, growing duller and fainter as the walls and terraces began to rise, then surged again with the arrival of the first crates of furniture. Even the pastry cook—the dairywoman’s rival, albeit not as cultured—the most vituperative Fury in this choir of ancients that included the shoemaker and the laundry supervisor from the Hotel Bristol, was stuck for anything new to say. She stood, silent and morose, attacking neat rows of éclairs with great swipes of her piping bag.