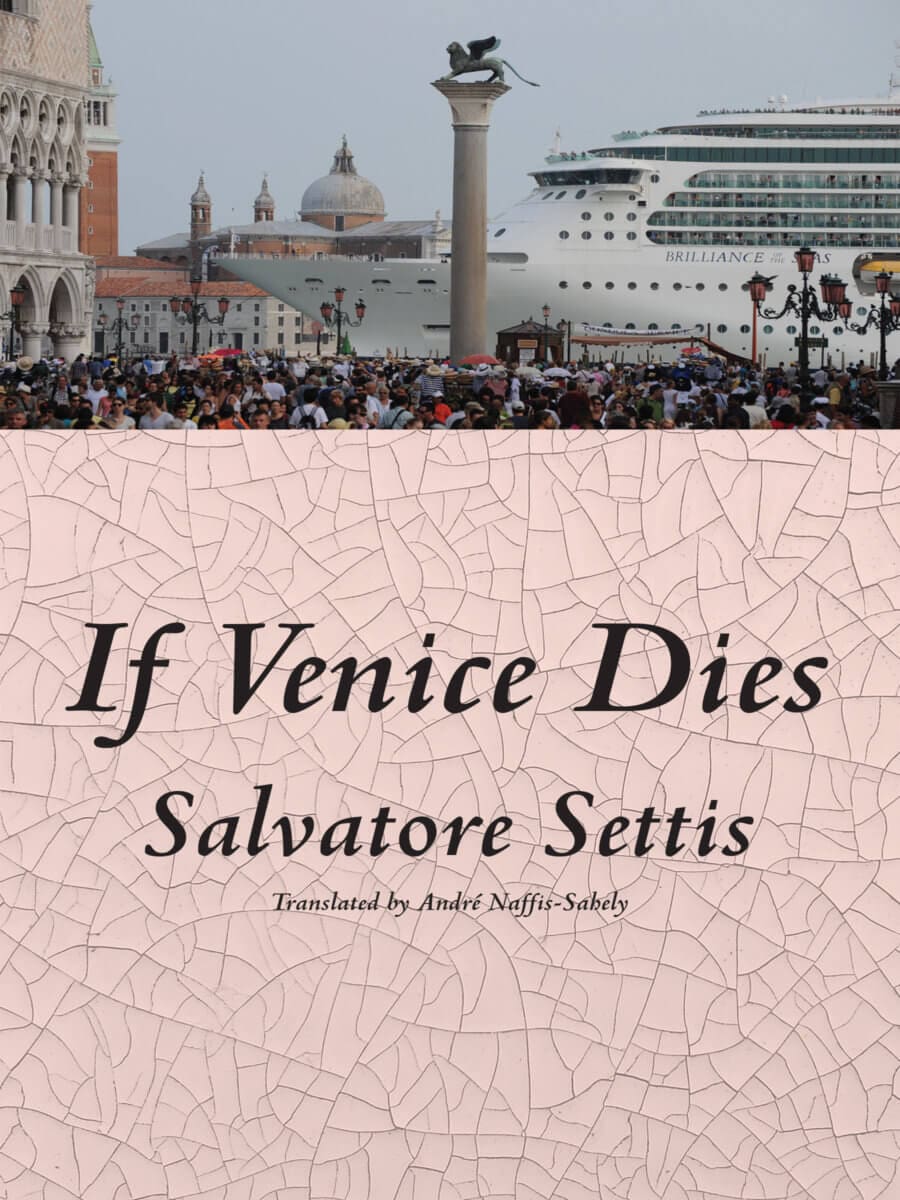

What is Venice worth? To whom does this urban treasure belong? This eloquent book by internationally renowned art historian Salvatore Settis urgently poses these questions, igniting a new debate about the Queen of the Adriatic and cultural patrimony at large. Venetians are increasingly abandoning their hometown—there’s now only one resident for every 140 visitors—and Venice’s fragile fate has become emblematic of the future of historic cities everywhere as it capitulates to tourists and those who profit from them. In If Venice Dies, a fiery blend of history and cultural analysis, Settis argues that “hit-and-run” visitors are turning landmark urban settings into shopping malls and theme parks. He warns that Western civilization’s prime achievements face impending ruin from mass tourism and global cultural homogenization. This is a passionate plea to secure the soul of Venice, written with consummate authority, wide-ranging erudition, and élan.

Excerpt from If Venice Dies

CHAPTER IX: Replicating Venice

Locked in its lagoon, Venice has nevertheless managed to inspire the world. The sudden collapse of St. Mark’s Campanile in 1902 and the swift move toward its reconstruction “as it was, where it was,” completed in 1912, triggered the construction of a wave of replicas—of varying dimensions—during the early 1900s, especially in the United States. Thus, one can see Venetian bell towers in the train stations of Seattle (1904, 242 feet tall) and Toronto (1916, 140 feet), the Daniels & Fisher Tower in Denver, Colorado (1910, 324 feet), on Berkeley’s campus (1914, 308 feet), Brisbane’s City Hall in Australia (1917, 298 feet), and Port Elizabeth’s City Hall in South Africa (1920, 170 feet). The imitations of St. Mark’s Campanile in New York, which are veritable skyscrapers in their own right, are still in use and are far taller than the original: the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company Tower on Madison Avenue (1909) is 698 feet tall, while the Bankers Trust Company Building on Wall Street (1910, 505 feet)—now known as 14 Wall Street—is topped off by a temple inspired by the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus. The death and resurrection of a famous piece of historic architecture directly led to these and other imitations which drew from its form in order to add a touch of nobility to their universities, train stations, department stores and city halls, but above all, their skyscrapers.

Even the city of Venice, California was founded during those years—in 1905 to be exact, by the tobacco magnate Abbot Kinney—and although it doesn’t have a campanile, it does have a Doge’s Palace, which truth be told is rather modest. There are still a few canals and once upon a time it even had gondolas and gondoliers. It was an immensely successful real estate venture, given that Kinney and his business partner owned almost all of the land on which the new city was built. Its original name, “Venice of America,” was an even more explicit reference to the Italian Venice. The idea was to build a compromise between a city and an amusement park, and to provide a little color for visiting tourists (the color, of course, was all fake) in order to lure them to the Pacific coast, which, needless to say, didn’t resemble Venice in the slightest. Venice, California was therefore a direct predecessor of Disneyland (which opened in 1955, just 50 miles down the road); Venice’s remaining canals were listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1982.

There are twenty-seven other Venices in the United States, and twenty-two in Brazil; Fort Lauderdale in Florida is also known as the “Venice of America,” just as Aveiro is called is the “Venice of Portugal,” while cities such as Amsterdam, Birmingham, Bruges, Copenhagen, Giethoorn, Hamburg, Saint Petersburg, Stockholm, and Wrocław have each been called the “Venice of the North.” The various cities wearing the badge of “Venice of the East” like Bangkok, Hanoi and Udaipur are almost too many to count: Japan alone has eight which have been granted that title. Not to mention the neighborhoods that have been called “Venice” around the world, from Livorno to Le Havre, from Strasbourg to London (there’s an area in Maida Vale called “Little Venice”); or in Venezuela, whose name (again, “Little Venice”) was inspired by the sight of indigenous people’s houses on stilts in Lake Maracaibo. Very rarely do these cities or neighborhoods feature relatively successful imitations of buildings found in the original Venice; what generally ties them together is the fact that most have dense networks of canals that allow for a way of life that the real Venice pioneered and is still the prime example of.

In order to evoke Venice, in the context of a culture that is easily pleased, one merely has to bring up a canal, or a building whose image is reflected in its waters, a doorway or two giving directly onto the water, or even just a few boats moving alongside some houses. The opposite, however, does not happen: as far as I’m aware, nobody has ever called Venice the “Stockholm of the Adriatic.” The image of the one and only Venice is far too vivid for that, in fact it overwhelms other associations and is a touchstone. Multiplied by its myriad evocations, is the idea of Venice reinforced by this process, or does it instead splinter? Is the widespread fortune its name has enjoyed (which some argue is the most copied name in the world, even beating its closest competitors, Paris and Rome) linked to its picturesque appearance, or is it instead caused by the subtle interest it inspires due to its unusual take on urban living? Does it implicitly invite a desire to imitate its beauty, or evoke the tendency to consider it exotic and unlikely (and therefore “entertaining”)?

The idea of Venice as an amusement park wasn’t merely limited to early 20th century California. The Venetian Resort Hotel in Las Vegas, Nevada, features 4,000 rooms and its complex hosts an adjacent casino in the middle of a miniature Venice built from scratch. It features replicas of St. Mark’s Campanile and the Rialto Bridge in 1/2 scale, as well as canals with gondolas coursing through them, along with scaled replicas of the Doge’s Palace and the Piazza and Piazzetta of San Marco. The Venetian has offered its guests all this and more ever since Sophia Loren celebrated its opening aboard a motorized gondola in 1999. Of course, the ubiquitous skyscraper made its mark here too in the shape of the Venezia Tower, whose 36-story, 475-foot height added 1,013 suites to the complex, as well as a wedding chapel. Is that too kitschy? Yet when two prestigious museums—the Hermitage and the Guggenheim—wanted to open a kind of joint venture in Las Vegas in 2001—which was formally called the Guggenheim Hermitage Museum, but was informally known as “The Jewel Box”—they chose to situate it right inside The Venetian, showcasing works by artists ranging from Titian to Jackson Pollock, a disastrous move which forced the museum to shut its doors only a few years later in 2008.

In his 2007 book Welcome to Venice, journalist Guido Moltedo provides us with an inventory of this Vegas Venice, which is no longer unique, but as the book’s subtitle says, has been “imitated, copied and dreamed a hundred times.” To name just a few examples: in 2007, The Venetian Las Vegas spawned a kind of clone in Macao in 2007, which was just as gargantuan as its predecessor: The Venetian Macao Resort, replete with its own skyscrapers, gondolas, St. Mark’s Campanile and Rialto Bridge is the biggest casino in the world. In Kundu, Turkey, not far from Antalya, the Venezia Palace Deluxe Resort Hotel features approximate copies of the Horses of Saint Mark, which overlook the usual panoply of copies centered around the Campanile. This is an interesting example of reclamation, considering that the original Horses of Saint Mark were brought to Venice after the sack of Constantinople in 1204 during the Fourth Crusade. In fact, Istanbul is the location of Viaport Venezia (which is located in the Gaziosmanpaşa district): a pool of water surrounded by five skyscrapers, with 2,500 apartments between them (the tallest tower is 495 feet), which also features a shopping mall, various canals, Venetian-style bridges, and a few gondolas. The slogan which appears on Viaport’s website is: “You no longer have to travel to Venice to experience Venice.” There’s even a Venice in Dubai, in the shadow of Burj Khalifa, currently the tallest skyscraper in the world (2,716 feet), although this particular one only features a few canals and boats and doesn’t sport replicas of St. Mark’s Campanile and the Rialto Bridge. In Qatar, there’s another fake Venice dominated by grimly conspicuous skyscrapers.

The common thread in these examples is the impoverished transposition of Venice, whereby it is reduced to a picturesque accessory, a small-scale replica constructed with cheap building materials, but is nonetheless presented as the epitome of luxury. It seems that in order to experience Venice, one need only cross a little bridge over a fake canal while eying a useless gondola moored nearby. These fake Venices decorate five-star hotels or prestigious residential neighborhoods, just like in the Turkish Viaport Venezia, where a “perfect life you could not find even in Venice awaits you.” The skyscrapers that constitute this real estate venture, arranged around a pool of water, re-evoke (is this mere coincidence?) the ring of skyscrapers that might be built around the real Venice in 2060, as envisioned by the Aqualta project. Even when it comes to these fake Venices, one or more skyscrapers tower over the small-scale reproductions of St. Mark’s Campanile, looking down on it as a giant would a dwarf.

Yet nothing can compare to what is currently happening in China. Macao, with its legacy of Portuguese colonial rule, is almost an extension of the West (just like Hong Kong), and this might explain why it cloned Las Vegas’s fake Venice. However, all over the country, the massive population movements, coupled with the rapid industrialization of the countryside and the construction of megalopoleis have led to the radical destruction of historic towns and the symmetrical creation of French, Spanish, Dutch and English residential neighborhoods (as is the case in Huizhou). In order to provide a little color or flavor, there are even churches, which are actually used as theaters: whereas churches in European cities have been increasingly reutilized once the sacred edifice is no longer used as a place of worship, this becomes the primary function of churches in China, which were never actually used as churches to begin with, thus depriving said architectural from of any depth or meaning.

The New South China Mall in Dongguan, fifty miles northwest of Hong Kong, is the largest shopping mall in the world. The mall has seven zones modeled on just as many geographical areas, including Rome, Venice (with a St. Mark’s Campanile and various canals), Paris, Amsterdam, Egypt, the Caribbean, and California. The mall, which opened in 2005, has suffered from a severe lack of occupants and over 90% of its available stores have been vacant. As Bianca Bosker noted in her recent book, Original Copies: Architectural Mimicry in Contemporary China, a vast district which closely mimicked Venice was built not far from Hangzhou and is called Venice Water Town:

“As in the original Venice, the town houses are painted in warm shades of orange, red and white. The windows feature balustrades and ogee arches and are set into loggias framed in stone. The structures blend Gothic, Veneto-Byzantine and Oriental motifs and overlook a network of canals on which “gondoliers” navigate gondolas under stone bridges. The property’s crown jewel is a replica of Saint Mark’s Square and the Doge’s Palace in the town square, complete with Saint Mark’s Campanile; a pair of columns topped with gilded statues of the lion of Saint Mark and Saint Teodoro of Amasea, the patrons of Venice; and ornate patterned tiles on the façade of the ‘Doge Palace.'”

According to Bosker, these architectural ghosts are supplanting the authentic historic city centers of Chinese cities, which were demolished because they were a standing reminder of poverty, whereas Alpine villages, Italian squares and English churches seemingly evoke the prosperous societies with which China’s nouveau riche wish to identify. Could this be explained by the fact that, as Umberto Eco noted, “baroque rhetoric, eclectic frenzy, and compulsive imitation prevail where wealth has no history.” Bosker has suggested another explanation, and in her book she retraces the long Chinese tradition of “thematic appropriation” of foreign architectural styles, which began “in the late third century BCE,” when after having conquered the last six independent kingdoms, the First Emperor “replicated each of the [dethroned rulers’] local palaces (probably in miniature, perhaps two-thirds scale) along the banks of the Wei River outside his own capital city of Xianyang.” It is more likely, however, that this is the result of the passive mimesis of those who chase wealth, in Eco’s words, which has combined with a civilization that is used to absorbing others, all of which has taken place under the aegis of runaway capitalism, even though it is led by a nominally Communist Party.

This is architecture as ersatz, a deception, a simulacrum. Ersatz (literally meaning substitute or replacement) is a German word which worked its way into English during the two world wars, when it was used to describe a substitute good that was usually of inferior quality to the original good that it replaced (as was the case with Ersatzkaffee, which was called Caffè d’orzo in Italy and was made from barley rather than coffee beans, and so forth.) While the St. Mark’s bell towers which were replicated in the United States and elsewhere in the early 20th century were respectful homages to the one in St. Mark’s Square, the ersatz architecture of these fake Venices supplant authenticity, memory and history with their impromptu set designs, and in order to do so employ drastic selective criteria. For instance, none of these fake Venices include a replica of St. Mark’s Basilica (which is simply too complex to reproduce), while it never even crossed anyone’s mind to feature replicas of the nearby Giudecca, or Campo San Polo, or the Basilica di Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari, or the Scuola Grande di San Rocco. Thus, in order to clone Venice, one must first mutilate it, getting rid of 99% of it to reduce it to a caricature of itself, stripping all the meat until one is left with a bare bone. But the very moment that it is flaunted as a model, it automatically rips all the charm, richness and diversity out of its urban fabric. Nevertheless, there is no shortage of those who think that Venice (the real one) can draw two-fold advantages from its pale imitations: it can redirect a great many of the tourists who are afflicting it to these imitations, and demand royalties from those who wish to copy it. Yet what if the exact opposite were actually happening? What if the fake Venices scattered around the world are corrupting the real Venice’s image of itself? What if they became its hidden model? What if a Venice without Venetians tried to find its own identity in places like Las Vegas, Dubai, or Chongqing?