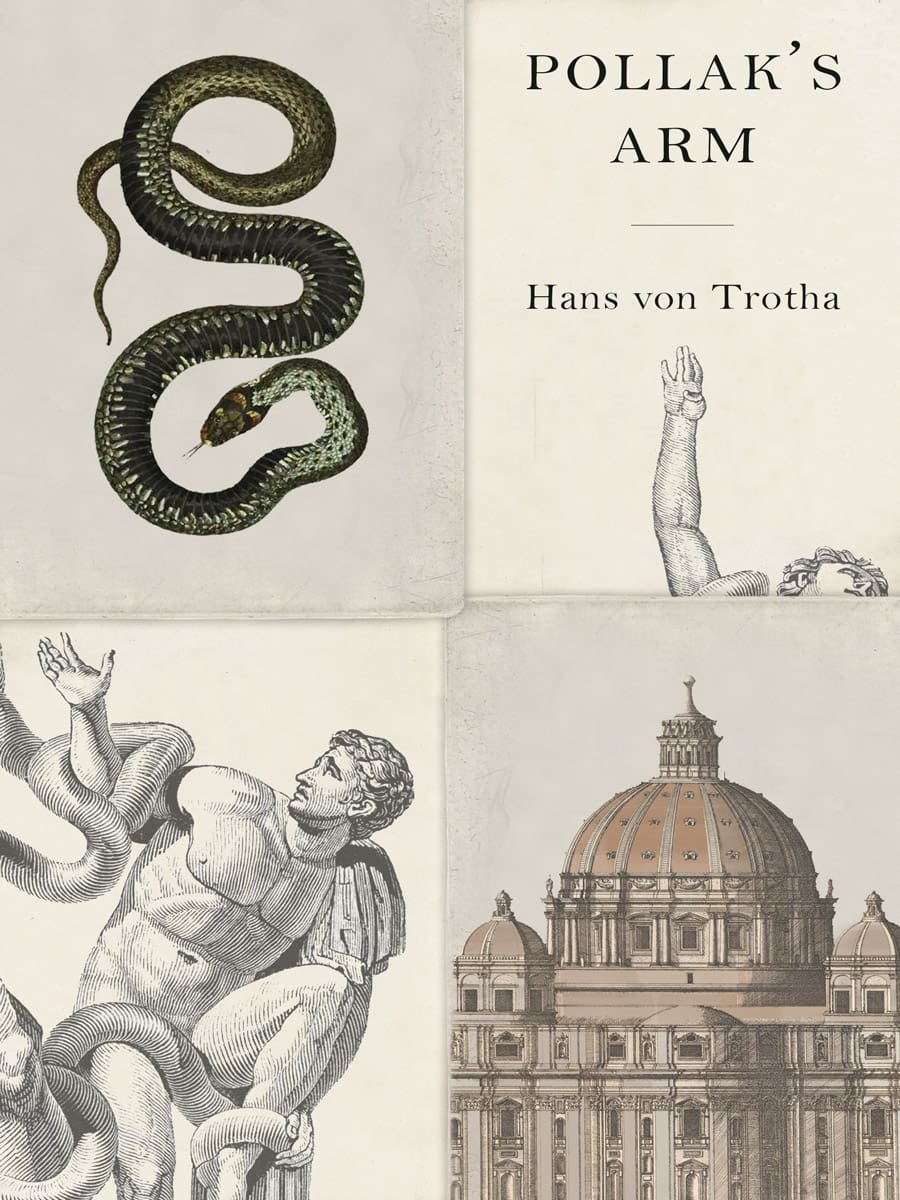

October 16, 1943, inside the Vatican as darkness descends upon Rome. Having been alerted to the Nazi plan to round up the city’s Jewish population the next day, Monsignor F. dispatches an envoy to a nearby palazzo to bring Ludwig Pollak and his family to safety within the papal premises. But Pollak shows himself in no hurry to leave his home and accept the eleventh-hour offer of refuge. Pollak’s visitor is obliged to take a seat and listen as he recounts his life story: how he studied archaeology in Prague, his passion for Italy and Goethe, how he became a renowned antiquities dealer and advisor to great collectors like J. P. Morgan and the Austro-Hungarian emperor after his own Jewishness barred him from an academic career, and finally his spectacular discovery of the missing arm from the majestic ancient sculpture of Laocoön and his sons. Torn between hearing Pollak’s spellbinding tale and the urgent mission to save the archaeologist from certain annihilation, the Vatican’s anxious messenger presses him to make haste and depart. This stunning novel illuminates the chasm between civilization and barbarism by spotlighting a now little-known figure devoted to knowledge and the power of artistic creation.

Watch a video of author Hans von Trotha discussing Pollak’s Arm with historian David Kertzer, winner of the Pulitzer Prize for his book The Pope and Mussolini, at an event sponsored by Rizzoli Bookstore and the Centro Primo Levi in New York. Click here to watch.

Excerpt from Pollak’s Arm

It seemed Pollak was trying to avoid or ignore my call to alert his family and prepare. He had moved to the window and stood there like a figure seen from behind in a Caspar David Friedrich painting, the fading light of a rainy fall afternoon providing the backdrop. I had clearly failed to convey the urgency of my mission. Either that, or he chose not to acknowledge it. I didn’t know what to do. When I set out for Palazzo Odescalchi, it never crossed my mind that our talk might drag on. Danger was at hand. It was obvious. I thought it must be obvious to him too.

Is that the car? he asked. The driver just got out. He’s coming inside. He’s in uniform. SS.

Those words revealed Pollak’s fright at what he saw, but even so, his response was far more muted than seemed appropriate to me. Nevertheless, I felt a momentary hope that the shock might remind him of what was happening and bring him to his senses. I informed him of our cover, assured him that the uniform was no cause for concern, that the driver was loyal—to us, that is. I went to the other window and watched the driver below. He approached the building, then disappeared through the tall gate between the pillars of the baroque façade. The vehicle looked abandoned on the street. A moment later there was a knock on the door to Pollak’s apartment. Though we knew who it was, we both jumped.

Shall I get it? I asked him. I walked down the corridor and opened the door. The driver whispered that he could not wait on the street much longer, or at all, once the sun set. He gave me an address a few doors down and around the corner. He would wait there in the courtyard. He, too, implored us to hurry.

Doctors, midwives, and priests are exempt from the nightly curfew, I said to Pollak as I returned. I am none of those things. For that reason, we have to hide the car. And we have to hurry. At whatever cost, we must make it to the Vatican before nightfall.

Pollak appeared indifferent to the conversation I had had with the driver. He was more interested in the make of car.

He was still standing by the window. He must have seen the driver leave the house, climb back into the car, turn around, and drive up the street.

I don’t know, I said. I’m not sure. Mercedes?

Strauss had the same one, Pollak said. The very same one. Could that be? Or was that too long ago?

Strauss? I asked. He interpreted my involuntary response as an invitation to continue his story.

I have guided many, many people—hundreds, easily—through the collections of Rome, the major private collections in particular. No one has ever known them as well as I. People knew that in Europe, but not just in Europe.

Please, have a seat, he said for the first time, gesturing toward the bookcase and a table with armchairs positioned at either end. I politely declined and stood demonstratively near the door. He did not sit down, either, but remained where he was by the window. Then he told me about J. P. Morgan.