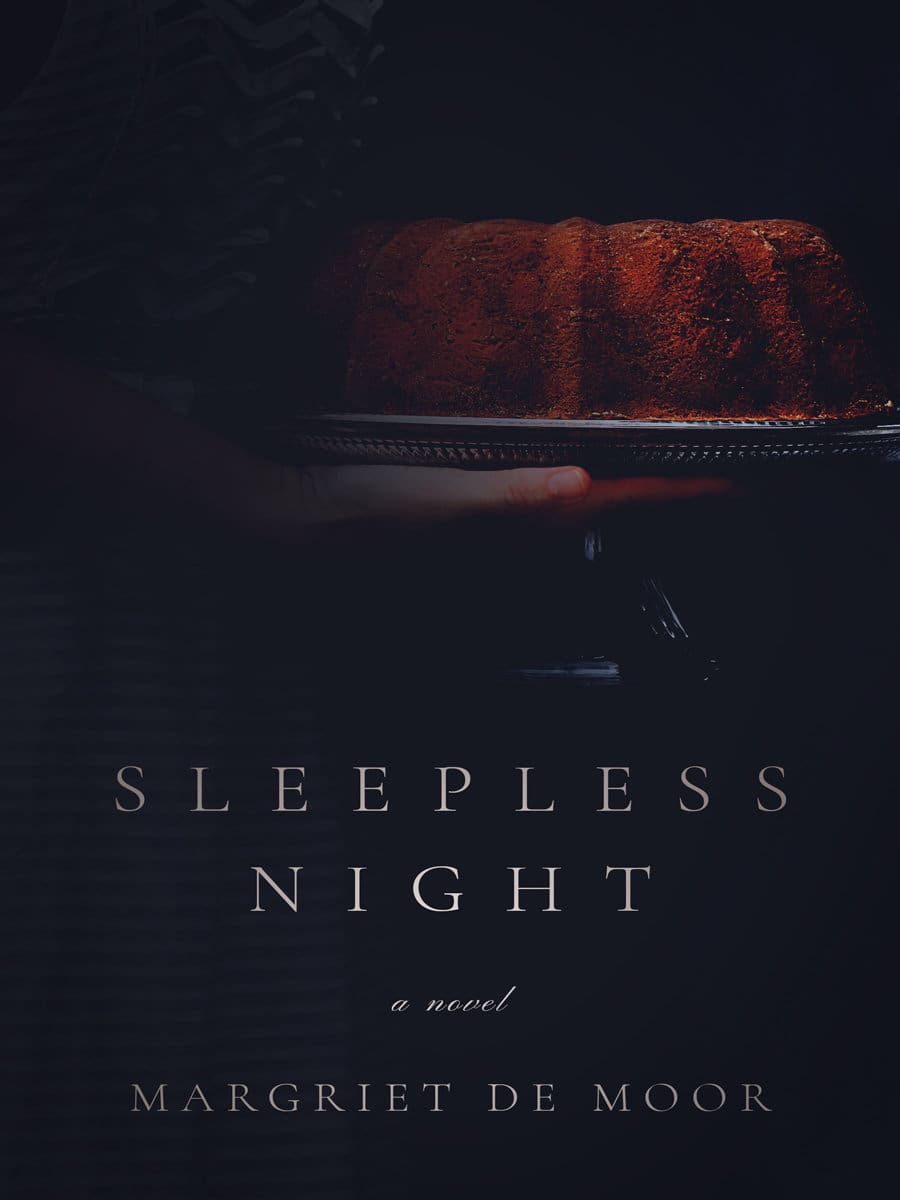

A woman gets up in the middle of a wintry night and starts baking a Bundt cake while her lover sleeps upstairs. When it’s time for her to take the cake out of the oven, we have read a tale of romance and death. The narrator of this novel was widowed years ago and is trying to find new passion. But the memory of her deceased husband and a shameful incident still holds her in its grasp. Why did he do it? Margriet de Moor, master storyteller and one of Europe’s foremost novelists, recounts a gripping love story about endings and demise, rage and jealousy, knowledge and ambiguity—and the possibility of a fresh start.

Download the Sleepless Night Reading Group Guide.

Author Margriet de Moor talks about why she wrote Sleepless Night in this video.

Excerpt from Sleepless Night

A special calm is needed to make this dough. It’s wise to have everything on hand before you start. Flour. Salt. Sugar. I take the big bowl, dissolve the yeast in milk. You knead the mixture for five minutes first, and only then do you add the eggs. From that moment on, you have to be careful. Yeast and eggs are extremely volatile ingredients. They make the mixture swell. They give off gases. And, a process which never fails to astound me, they double the original volume. I start by raking my fingers firmly through the ingredients.

It’s nonsense, of course, to suppose that I do not remember Ton. Every woman remembers her husband. Things happened. Pleasant things, most likely, natural, too—so natural they seemed to happen of their own accord and left no impression. On Sundays, we were in the habit of having breakfast under the pear trees. We sat on rickety antique chairs. Ton boiled the eggs and served them up in an oven glove to keep them warm. How often would it have been? A summer long, a handful of times? I laid a garland of nasturtium around his plate, trickled honey into the calyxes of the edible flowers. Why? Out of love? Some sentimental notion? Because that morning my hair had fallen into a fetching wave?

I press the base of my thumb into the dough. The surface still crumbles slightly. With slow, steady movements, I squeeze the mass together. I work in silence. It’s unthinkable that the mixer might shred the intense stillness of the night. The machine stands next to the stove, gathering grease and dust. I might as well toss it out altogether, for even during the day, when there could be no objection to using it, the notion never enters my head. Its nerve-jangling din is superfluous in any case. My fingers do the job as well as any pulsating dough hook, if not better. It’s simply a matter of making sure your hands don’t get too warm and turn the mixture gummy.

Ton. His name was Ton. Not a name that struck a chord with me, it was just a good fit. It matched the way he walked and talked, the blue sweater he draped around my shoulders that day we went sailing. Oh, when I think of the ease with which he turned the boat into the howling wind and brought us to a clean halt six inches from the pier. By that time my lips were chewed raw; I tasted blood for hours.

I turn on the faucet and rinse my hands with cold water. Then I dust the counter with flour. It is an old-fashioned granite surface. The stone was still free of cracks, and Ton and I saw no need to replace it with stainless steel. It is a source of pleasure to me now. It’s true what they say, the coolness held in a slab of nature never disappears entirely.

This is where things get ugly. I plant my feet wider apart and take a deep breath. In the dead of night, I begin to pound away, slamming my fists into the pale, pliant lump in front of me. Just as well there’s not another living soul around to witness this. It’s like a scene from a nightmare, one of those silent terrors that leave you swallowed up by some unreal entity, clingy and elastic. Of course I remember my husband. All I have to do is start at the beginning, with an image I can call to mind effortlessly, at any given moment.