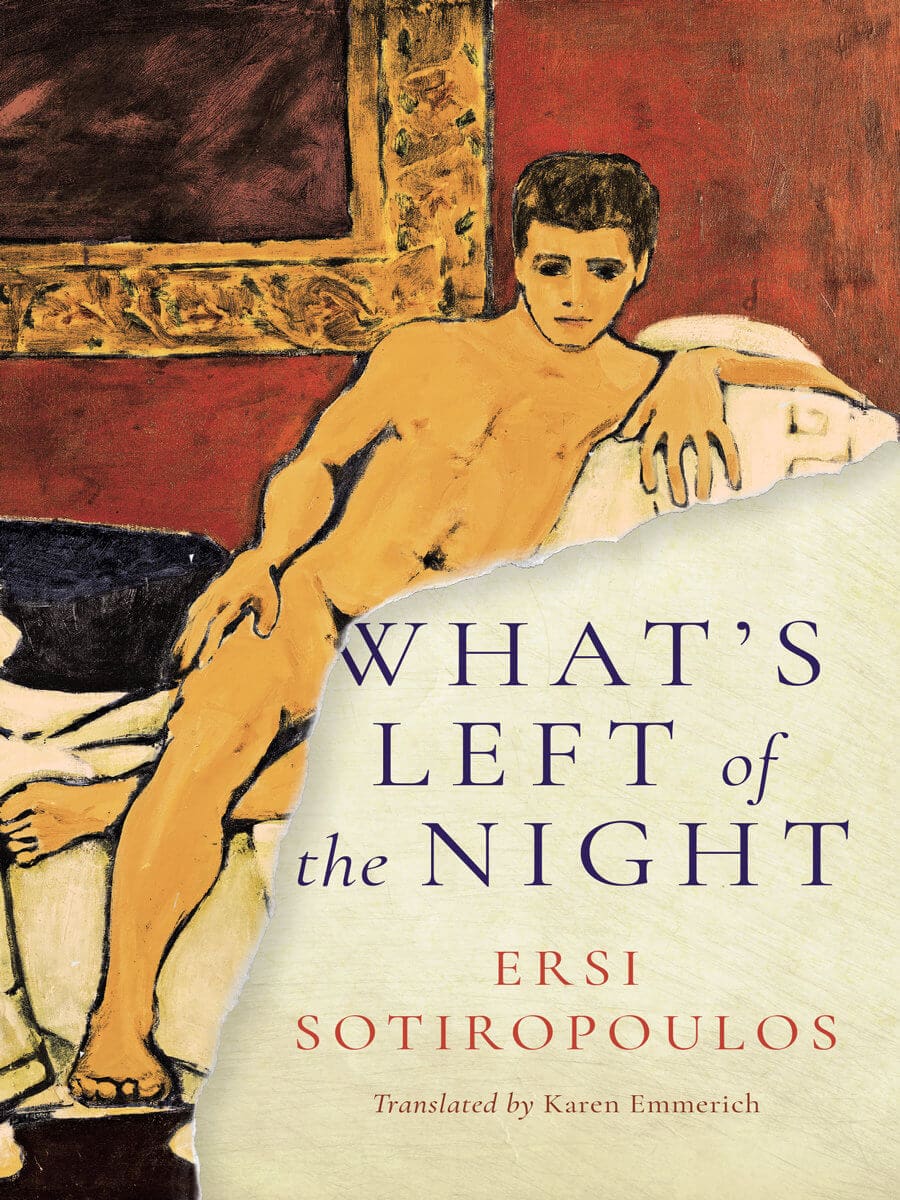

—NATIONAL TRANSLATION AWARD WINNER—

In June 1897, the young Constantine Cavafy arrives in Paris on the last stop of a long European tour, a trip that will deeply shape his future and push him toward his poetic inclination. With this lyrical novel, tinged with a hallucinatory eroticism that unfolds over three unforgettable days, celebrated Greek author Ersi Sotiropoulos depicts Cavafy in the midst of a journey of self-discovery across a continent on the brink of massive change. He is by turns exhilarated and tormented by his homosexuality; the Greek-Turkish War has ended in Greece’s defeat and humiliation; France is torn by the Dreyfus Affair, and Cavafy’s native Alexandria has surrendered to the indolent rhythms of the East. A stunning portrait of a budding author—before he became C.P. Cavafy, one of the 20th century’s greatest poets—that illuminates the complex relationship of art, life, and the erotic desires that trigger creativity.

Excerpt from What’s Left of the Night

Eyes closed, I turned toward you in bed. I stretched a hand through the half-light to touch your shoulder. That exquisite curve, the pale skin, paler against the dirty sheet. Nothing written on skin can be erased, I told myself. Five years ago, at a similar hour, you stirred in your sleep and your thigh brushed against me. I was still wearing my shirt. My hand slid over your chest, which was hairless and tawny with an undertone of ochre. I remember it strong, hairless, bright. The line of your mouth, that pink, open circle, and the gleam of a tooth, barely visible. A bit of dried saliva. I traced your lips with my fingers. Then my hand crept lower, lower still. You breathed, snoring slightly. In your sleep you rolled over and wrapped your arms around me. You murmured a word I didn’t know. Perhaps you were thirsty. My hand opened and closed …

A shudder swept over the empty bed. I’d left the window open and the curtains fluttered in the Parisian breeze. It was time I abandoned these rêveries. John would be waiting in the lobby.

The earth still seemed flat then, and night fell all at once until the end of the world, where someone hunched in the light of a lamp would be able to see, centuries later, a red sun setting over ruins, would be able to see, beyond seas and ruined harbors, countries lost in time living in the glow of triumph, in the slow agony of defeat. History repeats itself, he thought, though he wasn’t sure whether it really was repetition. His talent and persistence alone would allow him to see. Gripping his pen, he listened. Sounds, lights, smells, it all came flooding back. It was night once more on the flat earth. Voices reached his ears. A strain of cheap music from Attarin where the shops were open late, the sound of a barrel organ whose saccharine melody swelled and overflowed and climbed the muddy stairs. In the rooms upstairs limbs mingled on threadbare sheets. For half an hour of perfect pleas-ure, half an hour of absolute, sensual pleasure. Limbs, lips, eyelids on the squalid bed, kisses, gasping mouths. Then they would leave separately like fugitives, knowing this half an hour would haunt the rest of their lives, knowing they would return to seek it again. But now all they wanted was for the night to swallow them up, and as each hurried down the stairs that unbearable tinkle of music greeted him once more, a wobbly chime that mocked the oppressive thud of his heart. The street outside was always deserted, and the footsteps of an invisible shadow would echo in the distance, then fade. He’d stand for a moment in the doorway, then button his coat and walk quickly away, hugging the wall, head bent, collar raised. And sometimes it happened, it had in fact happened, that his eyes would meet the eyes of another man skidding like a rat through the darkness, some nervous, well-dressed man coming from the other direction, heading hypnotized toward those same stairs, that same room, to roll over those same stained sheets.

And if the lovers don’t respond to your touch? he thought. If they’re warm, soft-skinned statues that receive all caresses with the indifference of works of art? That Platonic idea enticed him, but only to a point. The object of desire was so distant, so close. Lips, limbs, bodies. Lips, gasping mouths. That was what he should write about. So close, so distant. That was the purpose of art, to abolish distance.

He recalled the figure of a youth from years ago. Had it been in Constantinople? Yeniköy? A beardless youth working as an ironmonger’s apprentice, and as the boy bent half naked over the anvil, sparks flying onto his glistening chest, he saw his face lit heroically, imagined him crowned with vines and bay leaves. They hadn’t spoken, and he never saw him again. Who would write about him? Who would heave him up out of the oblivion of History?

Years later, someone hunched in the light of a lamp would be able to see a red sun setting over mythical cities, would see burning grass through rusted iron, where once a marble fountain spurted water and the last droplets ran dry in the evening light. He would see the crimson rays shining on the young body of the apprentice in Yeniköy, fleetingly illuminating a possibility, yes, a possibility that assumed substance, an almost material substance, as that same youth now weaved between the columns of an ancient agora among the crowds of Antioch or Seleucia, and many were they who praised his beauty.

That “years later” is now, he thought. He alone could see. Only he wasn’t yet ready. His impatience chafed at him, and contrived miserable, graceless poems, which he tore up in self-reproach. And then there was that clunky pastiche … A heap of adjectives and too-fine turns of phrase, the churning runoff of a lyricism he hated but didn’t know how to leave behind. How can I shake free of that sentimental burden? he wondered. Often during the day he felt useless, irresolute, a failure. The problem was Alexandria, the city stifled him. His provincial life, his circle of silly people with their unshakable self-confidence, the feluccas and fellahin, the landscape like a cobwebbed stencil whose heavy humidity sank into your bones—it all weakened his nerves. And often he determined, without really believing it, that he needed to erase the Alexandria within him if he really wanted to write.

But now he was in a foreign city that charmed and repelled him in equal measure, a cosmopolitan capital that glittered with refinement, whose smallest corner seemed large and important. He needed to resist his bad mood and find a way to enjoy these final few days of the trip. No more wavering, he thought, I’ll make a daily schedule and stick to it. He reflexively straightened his tie and descended the three steps into the hotel lobby.

“Monsieur Cavafy!” he heard someone call.