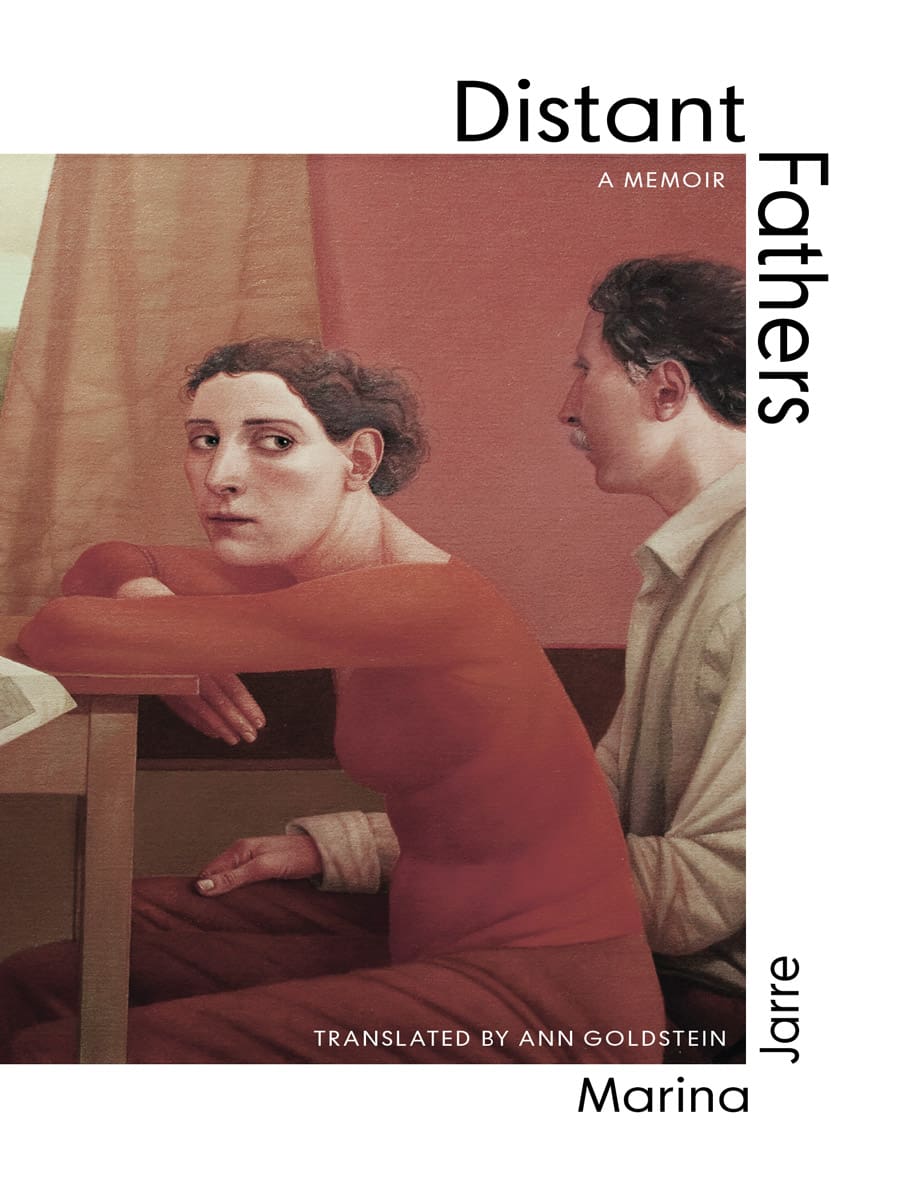

Cover art by Alan Feltus

This singular autobiography unfurls from author Marina Jarre’s native Latvia during the 1920s and ’30s and expands southward to the Italian countryside. In distinctive writing as poetic as it is precise, Jarre depicts an exceptionally multinational and complicated family: her elusive, handsome father—a Jew who perished in the Holocaust; her severe, cultured mother—an Italian Lutheran who translated Russian literature; and her sister and Latvian grandparents. Jarre tells of her passage from childhood to adolescence, first as a linguistic minority in a Baltic nation and then in traumatic exile to Italy after her parents’ divorce. Jarre lives with her maternal grandparents, French-speaking Waldensian Protestants in the Alpine valleys southwest of Turin, where she finds fascist Italy a problematic home for a Riga-born Jew. This memoir—likened to Speak, Memory by Vladimir Nabokov or Annie Ernaux’s The Years and now translated into English for the first time—probes questions of time, language, womanhood, belonging, and estrangement, while asking what homeland can be for those who have none, or many more than one.

Watch an insightful discussion of Distant Fathers with translator Ann Goldstein and Italian novelist Marta Barone, sponsored by Rizzoli Bookstore. Click here for video.

Download the Distant Fathers Reading Group Guide.

Excerpt from Distant Fathers

In recent years, as the astonishment of discovering that I, too, am getting older sweeps over me, I continue to dream—almost in compensation—beautiful, bright-colored, uninterrupted dreams, as if instead of dreaming I were writing, and on one of those rare occasions when a page pleases me immediately. Then I wake up satisfied, or maybe rather than satisfied—the word could suggest a contentedness I don’t feel—I wake up soothed, since even awake I recall those dreams roaming freely inside me much more precisely than many real events; they have the mark of something completed, even, let’s say, irrevocable, stated not with regret but instead as one might say, That’s how it is, it can’t be otherwise, the circle is closed and within that circle your life stands still in all its colors, but not one more.

I dreamed, for example, of walking along the streets of an entirely Gothic city together with nameless friends; the architraves of the portals were carved as if they had been wood, and so, too, were the cornices of the windows and even the edges of the sidewalks. Of the colors of the sculptures I recall mainly a carmine red that in the dream I liked immensely.

Another time, I entered a courtyard I had glimpsed in reality during a period when I was wandering through Turin neighborhoods in search of a courtyard suitable for a film to be based on a book of mine. The courtyard was bursting with white flowers, their petals transparent but the clusters full and thick, and someone told me I could pick them; while I gathered a large bunch I heard the sound of cars passing on the other side of the decrepit walls that made up three sides of the courtyard (on the fourth there was a palm tree), and I also heard many people talking inside the run-down buildings. Both the sound of the cars—maybe behind the palm tree there was a highway—and the voices were cheerful. Besides—this was the predominant sensation of the dream—the flowers were wild, and I could pick lots of them, as many as I wanted, and then leave the courtyard freely.

Thus I dreamed many times of returning to Torre Pellice, to the house of my Waldensian grandparents, where I lived between the ages of ten and twenty, placed in the care of my maternal grandmother, after my parents’ divorce. The dream leads me continuously from the house to the lawn and from the lawn to the house. This is always open, flooded with sun, and both the ground-floor dining room and the room upstairs where my mother stayed during her sojourns with us are empty of furniture. I am me now and me then; sometimes I know that I have a child or all my children or even my grandson with me, but I don’t see them in the dream. I go from the house to the lawn through the garden, but I don’t even see it.

Something always happens on the lawn: once it’s full of water, another time it’s covered on one side by a long, green, plastic shed roof that runs above the vines planted by my grandfather, from the boundary wall at the far end up to the chicken coop. Sometimes I realize that the fruit trees have been uprooted, but I don’t mind because I know it’s part of some work being done on the lawn. There’s never anything below the low wall on the right, where a path descended directly through the fields to the Pellice river, and never anything beyond the boundary wall, either.

Sometimes, returning from the lawn to the house, I find myself in the kitchen, which unlike the other rooms is darkened by closed shutters and is full of furniture, pots and pans, dishes, placed all around on tables and shelves. Here and there I also see different foods, which I eat, and they’re good, though I don’t know what they are.

So I go back and forth and chat with Grandmother—even when I know it’s my mother, she has Grandmother’s face and words—and talk about my departure for Turin. Grandmother tells me to stay a few days more, the weather is good, I haven’t seen any of my old friends. She mentions a friend and neighbor I haven’t seen for twenty years. The names of schoolmates come to mind whom I didn’t much care about then and haven’t thought of since. But yes, I say to myself, I’ll stay longer. And here I feel an extraordinary sense of security: yes, I’ll stay home, in my home. And I’ll eat the good, formless, tasteless food: the sun comes in through the door and the open windows; it’s a September sun, warm and the color of gold. I’ll go out to the lawn and then return to the house.

Here, constructed by my dream, is a past that didn’t exist and an encounter—with my grandmother and my mother—that didn’t exist, either. Words not spoken, or, rather, not spoken in that serene gilded light, in a house that’s open, and a little untidy. Once I even dreamed of long, frayed curtains on the dining room windows, which were much bigger than the real ones, curtains of a striped fabric like a beach umbrella, still pierced by the sun’s rays.

These bright-colored dreams escorting me from middle age to old age have, it seems to me, a common meaning, even if the images that compose them come from different settings. Whatever their psychological and imaginative material, however—honed as I am by rivers of reflections and recognitions, I could reconstruct it almost piece by piece—they all pretend that I have resolved and accepted. That I no longer fear any encounter. That I am able to look toward the end as it approaches, enjoying all the colors of life.